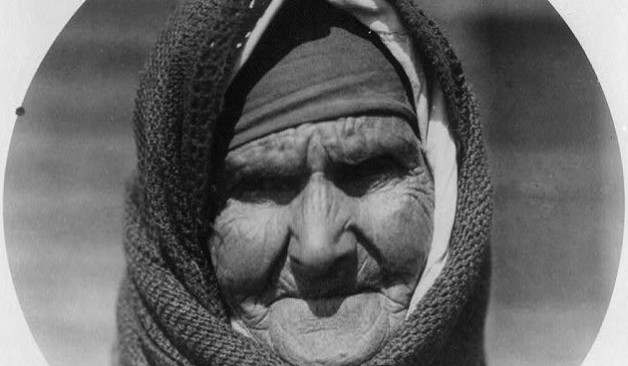

Last year a Greek food company produced a series of creative and wildly popular ads that juxtaposed modern young people doing what modern young people do—cohabiting, dressing immodestly, and being a stay-at-home dad—with a wizened old Greek grandmother (Yiayia) laying down the law in a brief but forceful way. (My favorite line: “Are you two married? But you living together, eh? You are going to hell!”)

In the wake of the Obama mandate on contraception, a chorus of Catholic bloggers produced a distinctly Yiayia-like solution to the widespread problem of Catholics flouting Church teaching on a host of moral issues: tell them they are going to hell.

Ordinarily level-headed writers conjured gleeful idylls in which bishops descend upon their dioceses like Rambo, laying public sinners and heresy to waste with rapid-fire excommunications, and priests replace their homilies with booming pulpit declamations against their congregations’ wicked ways. Some commentators thought the Obama mandate was a sign that the time for carrots has passed, and that the primary solution for the Church’s moral problems should now be the stick.

Both Yiayia and these bloggers have made some important errors about the Christian life. There are deeply and critically true things in what they are saying, of course; morality does matter, the Church and its ministers do have an obligation to care for souls by moral guidance, and sometimes a short, sharp shock does awaken people to the temporal and eternal consequences of their actions.

But we would do well to attend to the errors. The scold assumes that people who are acting badly will change their ways if they just hear the truth told to them often enough. This is not true. Telling a cohabiting couple that they are going to hell will only convince them to change their ways if they already believe that hell exists, that it’s possible to go there, that their action in the world can influence whether they go there, that the Church has the authority to rule on what sends people there, and that you have the authority to speak to them about their personal decisions. Of these five necessary beliefs, many people only hold the first with any certainty, reserve the second and the third for Hitler, Stalin, and people who smoke, and reject the fourth and the fifth without much consideration.

Thus we have been led back to the deeper problem that undergirds the first. A certain kind of Catholic assumes that the fundamental problem in the Church today is a crisis of morality. This is not true. Behind the crisis of morality lies a deeper crisis: a crisis of faith. Christian doing follows Christian being, not the other way around. We must first decide for whom we will live, before we can decide how we are going to live. If I choose to live my life for myself, my neighbor, my country—anyone but God—then the Christian moral life will feel like an endless series of meaningless rules. If I choose to live for God through the grace-filled virtues of faith, hope, and charity, then the moral life is a path of love, freely offered and freely taken.

Getting people to follow the commandments—even if they are not Christian—is a very good thing, because the commandments express some central principles of the natural law, which means that they express the most important behaviors that are good and bad for humans. It is objectively bad for cohabiting couples to cohabit, just as it is objectively good for people to worship God. But guilting people into external compliance with the law is not enough to bring people to their supernatural end in God. This is why Christ told his disciples, “If you love me, you will keep my commandments” (Jn 14:15). The internal logic of the commandments is love of God, and without that driving force they cannot bring people to eternal beatitude. If Yiayia wants her grandchildren to stop scandalizing the neighbors, she can keep berating them about their lifestyles. If she wants them to live eternally with God, she would do better to invite them to believe in the God who gave the commandments.

Today’s scolds may be legitimately frustrated with the disjuncture between the moral chaos of contemporary culture and the lackluster Jesus-loves-you-so-just-be-nice homilies that too often resound from Catholic pulpits. But answering lax morals with fire-and-brimstone morals is not the solution. We will not see a spiritual rebirth in our culture until people come to believe that Jesus Christ is real, and that his love can shape the structure of their lives. We can only deal with the second-order problem of morals if we deal first with the first-order problem of faith.

Bl. John Paul II outlined a way forward out of our spiritual morass in his encyclical Redemptoris Missio, where he famously said: “The Church proposes; she imposes nothing” (39). The Church’s moral teachings are universally and perennially important, but not as sticks with which to beat people or as ideological constraints that must be imposed upon all willy-nilly. The Church does not exist for the sake of imposing moral rules; instead she exists to propose the person of Christ. In seeing Christ, we are changed, set free from the slavery of our own selfishness and the errors of our ways. We are freed to respond in love to Christ. The way forward is not Rambo clergy and nagging Yiayias. The way forward is the offer, the challenge, the proposal that Bl. John Paul said is thematic for the Church and her mission: “Open the doors to Christ!”

✠

Image: Library of Congress, Old Greek Woman