Shakespeare was a secret Catholic, more and more readers claim. Might he also have been a surreptitious Dominican—a tertiary like St. Catherine of Siena?

An argument for Shakespeare’s connection with the Dominicans could, in a certain sense, actually be stronger than those for his personal affiliation with the Catholic creed. The theories advanced in support of “Shakespeare the Catholic” are often contradictory, the evidence circumstantial at best.

Yet it is clear that Shakespeare did enjoy a unique—and often overlooked—connection to the Order of Preachers. By the end of his career, his name was closely associated with the Blackfriars (as Dominicans are commonly known in England, thanks to the distinctive black cappa). It’s an association that deserves particular attention now, with the confluence of three major anniversaries: the 800th Jubilee of the Dominican Order, the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, and, next year, the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation.

The link between the Bard and the Blackfriars consists in their shared use of a building—a large hall that was originally part of the Dominican priory in London. Shakespeare ended up working where the Dominicans had lived, prayed, and studied—or, technically, where they ate (there is some debate among historians, but the hall had likely served as the friars’ “frater,” or dining space). Following Henry VIII’s seizure of the monasteries in 1538, the Blackfriars priory was given to a royal favorite, who razed some buildings, such as the church, and leased the others. By 1608, the old frater had been converted into a playhouse occupied by Shakespeare’s troupe. It provided them an alternative playing venue for the winter season, as Shakespeare’s Globe was an open-air amphitheater. Shakespeare thus spent the final years of his career writing with Blackfriars productions in mind. And in 1613 he rooted himself more firmly in the Blackfriars precinct, purchasing another of the old priory buildings. (His motivations for this purchase remain unclear, the subject of much speculation.)

Shakespeare not only knew Blackfriars’ historical significance but capitalized on it. It’s a rich history, worthy of consideration here, before returning to Shakespeare’s use of the space.

The Friars’ Blackfriars

After settling at Oxford in 1221, the Dominicans established a priory in the western suburbs of London, with funding coming from members of the nobility as well as the Crown. After some time, the friars relocated within London’s walls. More precisely, King Edward I paid for a section of the ancient Roman wall to be moved, so the City could absorb the mendicant preachers (pretty cool, right?). The new precinct became known simply as “Blackfriars.”

From their London priory, Dominicans served as royal confessors for a stretch of 144 consecutive years. They were also called upon to assist in state affairs as ambassadors and messengers. Politics followed them home, too. The large frater was utilized as a meeting place for Parliament, for the Privy Council, and for court ceremonies.

The King’s Blackfriars

King Henry VIII relied on Blackfriars even more than his predecessors, making it a significant site of political activity. Men of tremendous temporal power and religious virtue were familiar with the priory. When the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V of Spain, visited England, for example, Henry VIII lodged him at the Blackfriars guest house. Saint Thomas More presided as Chancellor over Parliament meetings held at the priory.

In 1529, with the King anxious to marry Anne Boleyn, he called for a trial at Blackfriars, to examine the validity of his union to Katherine of Aragon (Saint John Fisher would serve as a member of the Queen’s defense). After months of testimony, the cardinals presiding at the trial called for a recess instead of rendering a judgment, which enraged the King. After this Henry strained all the more to find the power to disunite himself from Katherine. What therefore transpired at the priory would, ultimately and ironically, contribute to its dissolution along with the expulsion of the Dominicans from England.

The Bard’s Blackfriars

Shakespeare was keenly aware of Blackfriars’ political history, going so far as to put that history onstage in one of his last plays, All is True (known later as King Henry VIII). Co-authored with fellow dramatist John Fletcher, the play explores episodes from Henry’s reign, including the trial of Queen Katherine at Blackfriars. The effect must have been something like going to Ford’s Theatre to watch a play about Lincoln’s assassination. The Blackfriars venue thus allowed Shakespeare and Fletcher to make the past present in a poignant way.

The play also examines a distinctively Dominican theme, that of truth, or veritas (the Order’s motto). “Truth” and its cognates occur no fewer than fifty times in the play-text. In this fictional realm of Henry VIII, truth proves simultaneously enticing but evasive, demanding and dangerous. Some characters seek to manipulate the truth, and a few are chastened by it. Several would hoard it if they could, and a noble few wish to serve it. But every character desires it, confirming what those late-medieval friars studying Aristotle would have known. In the end, the play resists easy classification (Pro-Protestant propaganda? An ironic rebuke of the Reformation?), but this seems fitting. Just as Blackfriars served various interests during its lifetime, so too does Shakespeare’s play about it.

✠

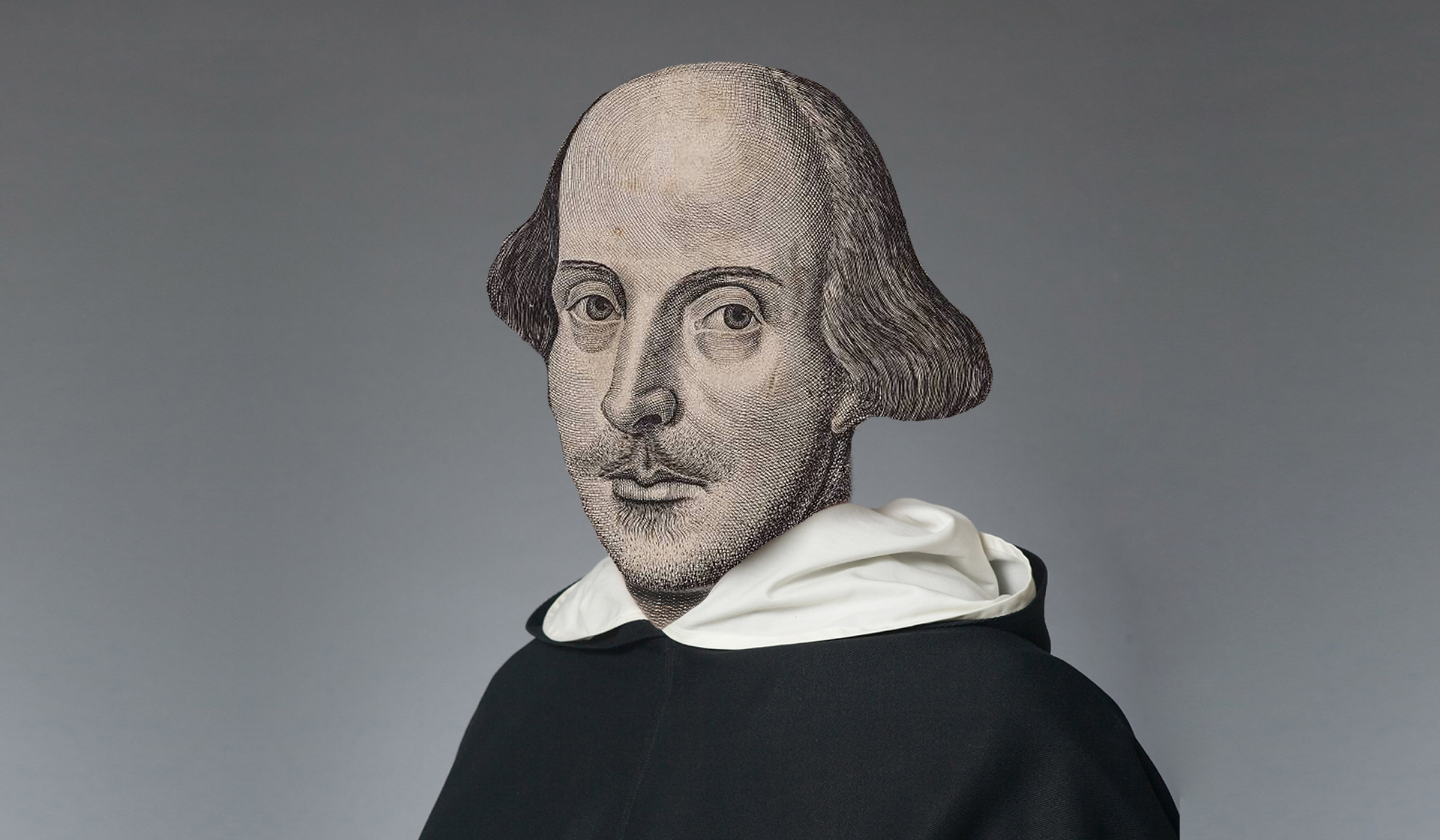

Image: Br. Irenaeus Dunlevy, O.P., William Shakespeare, O.P.