It was probably the weirdest instance of parental discipline I’ve ever had the privilege of witnessing.

It was at some summer evening gathering, with family and friends and pot-luck, those kinds of gatherings that blight one’s childhood and give one a lifelong aversion to lima beans, merry-go-rounds, and girls named Sandra. On this occasion, the protagonist was Cameron, four years my junior, the sort of histrionic nine-year-old who seems to be perpetually acting a one-man play, and who at the drop of a hat will belt out Mulan lyrics like a mini-Bocelli. Cheerful, clumsy, and cherubic, Cameron also (to his credit) bore more than a passing resemblance to the character Beans from the Disney Channel classic Even Stevens.

At a certain point in the evening’s festivities, Cameron had dropped his overladen Styrofoam plate, spilling hot dog, watermelon, mac ‘n cheese, and potato salad onto the grass. This sort of tragedy has broken lesser men, and Cameron was not unmoved. He let out a piercing shriek, and with a power and range that startled only those unfamiliar with his aforementioned Mulan stylings, leaned back and hollered to God in his heaven, “I’m a FAILURE!” To which his mother responded instantly and with breathtaking sternness, “Cameron! We don’t use that word.”

It was precisely the same tone and expression most parents use when they hear their young progeny swear a cuss, or see the young son and heir practicing surgery on the cat. Nary an ounce of sympathy for poor Cameron’s crise existentielle.

Needless to say, Cameron’s anguished cry became a popular refrain in the Clarke household as an acknowledgment of human finitude, contingency, and general lament of the Fall. In fact, I have deep sympathy with Cameron. I am a failure.

Or am I?

A quotation of Mother Teresa’s comes to mind, one that is frequently (mis)applied to these sorts of occasions: “God has not called me to be successful; He has called me to be faithful.”

This is taken by some as a salutary reminder that we ought to direct our gaze beyond merely worldly goals and standards. However, it is also used with unsettling frequency to give our natural timidity and fear of failure a veneer of respectability, as if Mother Teresa had said “God has commanded that we not be successful, since he wants us to be faithful.” Phew. Thank God. I’m not a failure—I’m faithful.

To my mind, it is a willful misreading of Mother Teresa’s point to suggest that we can drive a wedge between success and fidelity, where failure is better known as faithfulness, and whoever is successful in the world has some ‘splainin’ to do.

On one level, we all are failures. And yet this, as St. Paul reminds us, is where God came to meet us. “But God shows his love for us, in that while we were yet sinners Christ died for us” (Rom 5:8). By his death, we are more than failures. We are given “power to become children of God” (Jn 1:12).

I think that this is what Mother Teresa is getting at. She is in effect proposing a new paradigm of success and failure, of victory and defeat, of fidelity and betrayal. New, but not original; she is not the source, but the echo of the only new thing under the sun, Jesus Christ, who said, “For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his life?” (Mk 8:36). What we crudely call “having priorities” St. Augustine called the ordo amoris, the order of loves. What do we love most? For what are we willing to give our whole life? How much weight do we place on being successful, or having all the knick-knackery that makes for a comfortable life? Or conversely, how much do we fear lacking that knick-knackery, or being unsuccessful? Mother Teresa’s point is that a Christian should not understand success (or failure) in a primarily worldly sense. Our “success” is in fact fidelity, and so inseparable from the cross of Christ.

And yet our worldly success is not entirely irrelevant to our faithfulness to the Gospel. We should be wary of too readily dividing this world from the next. Major League Baseball’s all-time stolen base leader, Ricky Henderson, never signed a contract with the proviso, “steal an insane number of bases.” But stealing bases proved to be the way in which he was faithful to the basic terms of the agreement. In a similar way, the particular circumstances in which we answer the call to be faithful to the Gospel may in fact demand of us a high and difficult level of excellence and “worldly” success.

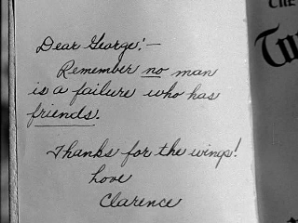

In the end, what counts as real failure? Clarence Oddbody offers a memorable answer in It’s a Wonderful Life: “No man is a failure who has friends.”

[one_half]

Clarence’s remark is in fact a striking commentary on St. Thomas’s description of charity as friendship with God. The saint is like George Bailey, toasted as the “richest man in town,” yet not on account of the cash piled in front of him, but because he has friends. Charity—friendship—should be our aim, in imitation of Christ who continually calls failures and makes them friends.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

[/one_half_last]

✠

Image: George Bailey (from It’s A Wonderful Life)