Doctors are prominent in my family’s lineage: my great-grandfather was a doctor, my grandfather was a doctor, my uncle is a doctor, and my brother is carrying on the tradition in the youngest generation. So naturally St. Luke, the “beloved physician,” has always attracted me. Except for his symbol, that is. An ox? Really? As compared with Mark’s lion, Matthew’s angel, or John’s eagle, Luke’s ox seems a consolation prize, as if he showed up late when the Holy Spirit was doling out emblems. Who would want to be associated with an ox?

These symbols of the evangelists are rooted in the Scriptures. Just to take two examples, in Ezekiel 1:1–14 they show up as the different faces of four living creatures sent to the prophet. And in Revelation 4:5–11 they are the four living creatures singing the Trisagion (“Holy, Holy, Holy”). The first ascription to the four evangelists seems to come from St. Ireneaus (ca. 120–202) in Against Heresies. There he gives the reason for St. Luke’s ox:

[The Gospel] according to Luke, taking up [Christ’s] priestly character, commenced with Zacharias the priest offering sacrifice to God. For now was made ready the fatted calf, about to be immolated for the finding again of the younger son. (3.11.8)

St. Augustine follows this identification saying that “Luke is intended under the figure of the calf, in reference to the pre-eminent sacrifice made by the priest.” The ox (or calf) signifies the priestly and sacrificial character of Christ in St. Luke’s account. This has never quite satisfied me. Surely St. John’s account emphasizes the sacrificial aspect of Christ with his title of “Lamb of God.” And St. Mark’s account is one long Passion narrative. Not to mention the temple scenes in St. Matthew. Is there any other reason that the ox might be fitting for St. Luke?

Well, what do you think of when you hear “ox”? After “big, dirty animal,” I think of a yoke. Oxen don’t just sit in the field; they are yoked together and put to work. An ox without a yoke is like an angel without wings—it just doesn’t seem right. And a yoke isn’t for one; like the disciples sent two by two, oxen work together. An eagle, lion, or angel can be by himself, but oxen are meant to be together.

And what is this yoke? St. Thomas, another saint associated with the ox, comments on Matthew 11:29: “Take, therefore, my yoke, namely, the gospel lessons. And he says yoke because just as a yoke fastens and joins the necks of oxen, so the doctrine of the Gospel fastens the people to its yoke.” The yoke of sin has been replaced, through the sacrifice of Christ, with the yoke of forgiveness and new life. And while this yoke of Christ will bring suffering in this life, it is still light and easy because, according to St. Thomas, it is a yoke of love:

“All who desire to lead a godly life in Christ Jesus will suffer persecution” (2 Tim 3:12). But [these persecutions] are not burdensome, because they are seasoned with the condiment of love; for when a person loves someone, it is not a burden to suffer anything for him. Hence love makes easy all difficult and impossible things. Therefore, if one loves Christ properly, nothing is difficult for him; consequently, the New Law does not impose a burden. (Commentary on St. Matthew’s Gospel 11.3)

There is something utterly fitting about this ox-yoke symbolism for St. Luke, who was St. Paul’s traveling companion and “beloved physician.” Being yoked to St. Paul must not have been easy, with all the ship-wrecks and persecutions and whatnot, but St. Luke’s love of his dear friend is found in the careful account we have of St. Paul in the Acts of the Apostles. The ox might not be as noble as an eagle, as regal as a lion, or as splendid as an angel; but an ox is a symbol of love and a shared mission, St. Paul and St. Luke sowing and plowing the field of the Lord’s harvest.

✠

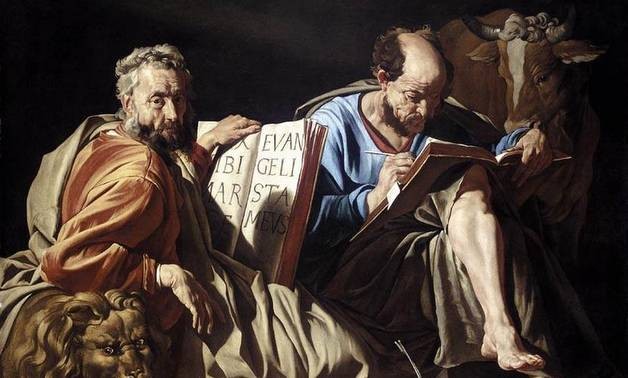

Image: Matthias Stom, The Evangelists St. Luke and St. Mark