“All men by nature desire to know.” Aristotle’s opening line of the Metaphysics was true of humans then and is true of humans now. Children still explore the front lawn on summer mornings, asking eternally: “What’s that?” But what about those things beyond simple understanding? What about complicated things, like macroeconomics or human decision-making? And what about God?

Any foray into apophatic, or so-called “negative,” theology, the teaching that what we know about God is more about what we don’t know about him, must mention its most venerable cheerleader Dionysius, a monk from the early 500s: “We ascend from the particular… to contemplate the superessential darkness that is hidden by all the light that is in existing things” (Mystical Theology, ch. 2).

Mystical journeys aside, we must ask: Is Christ that way? Isn’t he the light of the world, revealing God to us in words we can understand? Paul says, “God has made known to us in all wisdom and insight the mystery of his will… which he set forth in Christ” (Eph 1:9-10), but he also says, “As for knowledge, it will pass away. For our knowledge is imperfect” (1 Cor 13:9). Years back, I was struck by an anecdote in a First Things essay by David Bentley Hart:

The Christ of the gospels has always been—and will always remain—far more disturbing, uncanny, and scandalously contrary a figure than we usually like to admit. Or, as an old monk of Mount Athos once said to me, summing up what he believed he had learned from more than forty years of meditation on the gospels, “He is not what we would make him.”

Right when we think we have Christ pinned down, he escapes us. In trying to preach him, in public or in private, his mystery seems to defeat us. In my reading of late, I’ve found that various authors speak to the same point, that of Christ using images but always being beyond them:

God speaks to us, not in propositions and syllogisms, but in stern commands, in images, signs, gestures, whisperings of love, by both his manifest presence and his tangible absence, by both his words and his dramatic silences, always upsetting, overturning, the ordinary meaning of words and things. God’s logic may thus be compared to a logic of fire, which enkindles everything it touches. (Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis, Fire of Mercy, Heart of the Word, 42-43)

Christ clothed himself in the archetypal images of Israel, and then began to do and to suffer. The images were further transformed by… being combined in his one person. What sort of victorious David can it be, who is also the martyred Israel and the Lamb of sacrifice? What sort of new Adam can it be, who is also the temple of God? And what sort of living temple can it be, who is also the Word of God whereby the world was made? (Austin Farrer, The Glass of Vision, 109)

It is the most difficult mission imaginable… to convince men, by using all means of thought and evidence available, of something that lies beyond all the categories accessible to men; that God is triune love. This could be demonstrated only through Christ’s word, work, conduct, and suffering… even though before the coming of the Spirit no one was able to glimpse the seamless whole in the scattered pieces. (Hans Urs von Balthasar, You Have Words of Eternal Life, 53-55)

Christ clothed himself in what came before him. He is like Moses and David and a prophet and the Passover lamb. But he is not these things. He is God. Even after his coming among us, we must sing: “How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways” (Rm 11:33).

To follow Christ is to be humbled, not just by our sinfulness but by the poverty of our minds. But there is joy, in eternal life and this life. Someday, says Paul, “I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood” (1 Cor 13:12). All men by nature desire to know. Even truer, all men desire by nature to be known. God assures us we already are, and for now that makes all the difference.

✠

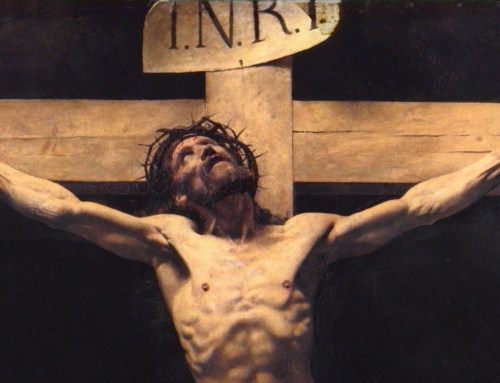

Image: Meister Bertram von Minden, Grabow Altarpiece (detail)