Would God have become man if man had never sinned?

An odd question, perhaps, but one which St. Thomas takes the trouble to answer with characteristic intellectual humility:

Such things as spring from God’s will, and are beyond the creature’s due, can be made known to us only through being revealed in Sacred Scripture, in which the Divine Will is manifested to us. Hence, since everywhere in Sacred Scripture the sin of the first man is assigned as the reason of the Incarnation, it is more in accordance with this to say that the work of the Incarnation was ordained by God as a remedy for sin; so that, had sin not existed, the Incarnation would not have been. And yet the power of God is not limited to this; even had sin not existed, God could have become incarnate.

God’s omnipotence, on the one hand, and the testimony of Scripture, on the other, lead us to believe that, although God could have become incarnate in a sinless world, He would not have done so. Still, we may ask, if He had done so, why would He have done so? St. Thomas does not answer this question directly, but, when considering the Incarnation in a more general way, he does say that it was fitting, not only as a remedy for sin, but also simply as an expression of God’s goodness: “It belongs to the essence of goodness to communicate itself to others . . . [and] it belongs to the essence of the highest good to communicate itself in the highest manner to the creature.”

It is stupefying, really, to think of God becoming incarnate merely to communicate his goodness to unfallen mankind—even more stupefying, in a certain sense, than God becoming incarnate to redeem us from our sins. It may also seem a rather fruitless piece of speculation. I would suggest, however, that this hypothetical scenario can help us better appreciate at least one aspect of the mystery of Christ’s birth, namely, the humble circumstances in which it occurred.

If Christ had been born into a world without sin, it follows—we might almost say it follows “by definition”—that the whole of creation would have welcomed him as jubilantly as the angels did on Christmas night: “Glory to God in the highest!” There would have been no search for hospitality, no rude feeding-trough for a bed, no flight from murderous Herod. The King of kings would have come into a world that recognized him as such, a world that worshiped and adored his ineffable love and majesty; He would not have silently slipped into a world that had become enemy territory. Indeed, although it is fitting that we now see the stable and the manger through the “rose-colored glasses” of our Savior’s love for us, we must also see them as what they were: the contemptuous rebuff of a sinful and fallen world.

Yet God, by submitting to the indignity of such poverty and obscurity, blesses it. In effect, He tells us that a poor and obscure life is the appropriate, natural, and beneficial condition of mankind after the Fall, the fitting exterior sign of our interior wretchedness, a salutary obstacle to our pride and self-sufficiency. Accordingly, the angels announce tidings of peace, not to the wise and powerful, but to the poor and simple shepherds, because, to the shepherds, who know their own need so well, the coming of God’s kingdom does, in fact, mean peace. Herod, on the other hand, and, with him, all who are persuaded by their power or prosperity that they are not wretched and poor, can only see the coming of God’s kingdom as unsettling, inconvenient, or irrelevant.

We moderns have our own pride and blindness, even if it is less obvious than Herod’s. In this egalitarian, scientific, “information” age, we habitually approach the mysteries of the Faith as so many mere facts, as items to be reviewed in a more or less casual way, analyzed from a critical distance, even evaluated on a strictly evidential basis. We respect, but do not reverence. We are interested, but not ravished. We read, but do not meditate. We experiment, but do not commit. These are signs of a spiritual and moral disease, and, if we would overcome that disease—if we would hear the Christmas Gospel afresh—we must learn from the shepherds, who teach us that the mysteries of God are revealed, not to the proud and the subtle, not to the “well-informed” and sophisticated, but to the humble and to those who suffer, to the innocent and to those who know their own sinfulness, to the teachable, and to those whose hearts are prepared.

✠

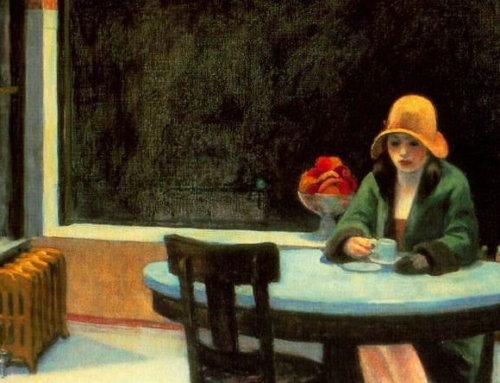

Image: Jacopo Bassano, The Adoration of the Shepherds