There is an alarming confusion cropping up in public discourse which has given me pause for reflection. It strikes me as the worst kind of confusion, and the most difficult to remedy, because it concerns the intention of hearts, confusing the noblest with the worst. You seek your neighbor’s spiritual well-being and you are accused of denying his very dignity.

It can certainly be seen elsewhere, but the national conversation about same-sex marriage provides a clear example. With good intentions, many Christians have sought to serve the good of their neighbor by objecting to the state solemnization of physically and spiritually harmful sex-acts. Increasingly, this fraternal solicitude is taken to be a damnable affront to gay dignity. It is a sin, explains Nathaniel Frank at Slate: “the sin of current opponents of gay marriage is an unwillingness to open their minds to change. There comes a time when there’s only one morally correct answer, and the space for having the wrong answer has dried up. I’d argue that time has come.” The Christian thinks he is engaged in a spiritual work of mercy, but Frank warns that he is in fact a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

This is all a bit frightening. The greatest love for our neighbor concerns itself with his spiritual good, and it is just this sort of love that is being confused for sin and even hatred. The confusion is not total, but any confusion of love for hate is disturbing. The lover’s smile taken for scorn, the friend’s gift received as poison, and the mother’s embrace greeted with terror all question the very possibility of lovers, friends, and mothers. There is real tragedy here: Your heart is opened and in that moment of vulnerability you become a monstrosity in the eyes of the one you love.

So, why is this love for our neighbor’s spiritual good taken for hate? And how can it be seen as love again?

First, our love looks like hate because our concern for souls chafes against the claim that human dignity is founded upon man’s power of self-determination. Our love calls into question the quasi-religious reverence paid to this supposed power. If our love is to be seen as love, the impotence of the power of self-determination must be exposed and the true foundation of human dignity must be laid bare. Our recourse is to point to the grave and from there to the only one who has conquered it. As far as I can tell, every project of self-determination has ended in death. Our love is great because our love takes death seriously and it points to the source of our dignity in the Son who prayed to the Father, “not my will, but thine, be done” (Lk 22:42).

Second, our love looks like hate because the life we propose often looks like death. By withholding endorsement for gay marriage, we implicitly suggest the alternative of lifelong chastity. For the man or woman with same-sex attraction, this certainly entails self-denial and the cross. Such a suggestion calls for honest self-examination: Have we embraced the cross ourselves and found freedom and joy in the embrace? When we propose the cross, do we speak of the love of God who gives us the strength to bear burdens for his sake? If our love is to be seen as love, we must be honest about the asceticism of the cross and point to the love that rewards self-denial with freedom and peace.

Third, our love looks like hate because we seem to advocate restraint in the enjoyment of all that the world has to offer. To some extent this is true: The ways of the world must be forsaken if we are to enjoy the peace and joy of intimacy with God. But why would our neighbor forsake certain apparent pleasures and delights of the world if this is the only world we’ve got? The world often appears unforesakeable because there is nothing better on offer. For our love to be seen as love, we must point in hope to the world that is to come and help our neighbor discern the spiritual delights that are on offer to us even now.

Will framing our opposition to same sex marriage in such a theological and eschatological way really allow us to be better heard in the public square? Probably not. But it strikes me that a philosophically-sound natural-law approach has not fared much better. Besides, it’s a bit too cheap: Why offer natural law without the promise of the grace which makes it observable? We need to tell the whole story, complete with its fantastic eschatological ending because Nathaniel Frank is right: “There comes a time when there’s only one morally correct answer, and the space for having the wrong answer has dried up.”

✠

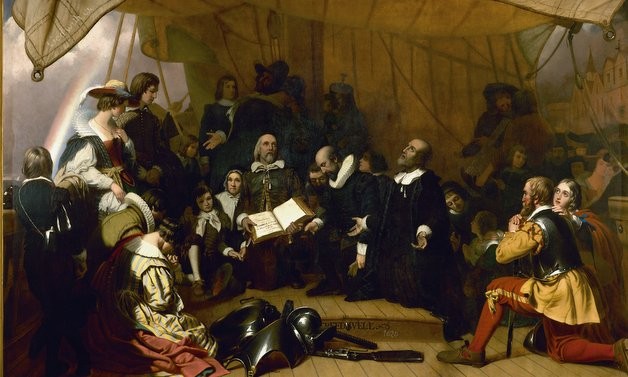

Image: Robert Weir, Embarkation of the Pilgrims