In the early third century Tertullian asked a famous question: “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” This question has been taken up by various Christians through the centuries (Martin Luther, Karl Barth, etc.) to raise the issue of reason and revelation, Greek philosophy and Biblical theology. It is also a rallying cry for the “Historical Jesus” studies of the last century: Athens in this case represents the speculative and dogmatic definitions of Church councils like Chalcedon and even Pauline theology, and Jerusalem represents the Gospels stories of Christ. As Marcus Borg says: “The Christological affirmations of the New Testament are metaphors,” and “when we literalize metaphors, we get nonsense.”

My immediate reaction is to paraphrase Flannery O’Connor and say “Well, if it just a metaphor, to hell with it.” Let’s not be hasty though, for I think we can use this ad fontes criterion to come up with something far from nonsense. I would like to outline one example of how we find exactly what Chalcedon defined about Jesus in the parables of Jesus himself.

I am not doing anything new here, rather relying on the excellent historical work of Anglican Bishop Tom Wright. His definitive statement on the subject is Jesus and the Victory of God and, among other things, he demonstrates that Jesus thought himself divine, even though he was a perfectly reasonable first-century Jew. Wright does this by reading Jesus’ stories and actions under the theme of a final Return to Zion of the King, who must be Israel’s God.

What I would like to do is make the Chalcedonian definition (Jesus is fully divine and fully human) plausible and intelligible in a first-century Jewish context through an examination of a recent Sunday reading: the parable of the vineyard and the wicked tenants (Matthew 21:33-43). The Gospel narration is simple: Jesus is telling a parable to the Jewish leaders in which a landowner leases a vineyard to some tenants. When harvest time comes the landowner sends servants who are beaten and killed, then finally sends his own son to collect his produce. The tenants kill him and throw him out of the vineyard. Jesus then quotes Psalm 118 (“The stone the builders rejected has become the capstone.”) in anticipatory judgment of the religious leaders themselves.

In this famous parable we can find, in the Jewish language of Jesus’ day, the two natures of Christ later defined by Chalcedon in 451 AD. How?

The Jews listening to Jesus would have heard a number of things in this parable which escape us unless we have spent time studying Scripture. First they would know that the vineyard in this parable was a reference to Israel itself based on Isaiah 5:7 (“The vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel”). The landowner of course would be recognized as YHWH, the God of Israel. Jesus, in claiming to be his son, would be making an implicit claim to identity with YHWH, something he had done on other occasions. But this is only half of what they would have heard.

The words of Isaiah 5 would not have come to their mind without being followed by the “servant song” of Isaiah 40-55. In this passage, deep as it is, we can discern a notion of the “servant of YHWH” being identified, not primarily with an individual, but with the people of Israel as a whole or as a righteous remnant who were continuing to undergo exile (even after the Second Temple restoration) until YHWH would finally vindicate his people and open the gates of salvation to all the nations through their suffering. In this reading (which follows Wright closely) the Jews would have heard Jesus identifying himself with this servant from Isaiah (Israel) in being cast out of the vineyard and punished as the rest of the servants.

Putting these two pieces together, albeit in a quick and sketchy fashion, we have Jesus telling a story about Israel and YHWH where he identifies himself with both the God of Israel and his people. If an interested bystander had asked one of the religious leaders whether Jesus was saying he was Israel herself or YHWH in this story, the only response could be “Yes.” In Jewish terms Jesus is fully identifying himself with the people of Israel and fully identifying himself with the God of Israel.

Finally, relating this to our Chalcedonian definition of Christ’s two natures (fully human and fully divine) we can see how this works in the following schematic:

Jewish Context: Jesus = people of Israel and YHWH, God of Israel

Greek Context: Jesus = a human being and God Himself

What the Church Fathers defined at Chalcedon was an entirely faithful translation of what Jesus himself said and thought about himself in his first-century Jewish context into the language of fourth-century Greek philosophy. My suspicion (and a wonderful thought experiment to all readers!) is that many if not all of the doctrines concerning Christ could be illuminated and established in this way. There is no need to fear good, solid historical work; we are not going to discover that the councils got it wrong, that Jesus isn’t who we think he is, or that Athens has demolished Jerusalem. Church doctrines concerning Christ are not mere metaphors on their way to being considered nonsense, Jesus is who the Church councils says he is, and it turns out that Athens has quite a lot to do with Jerusalem, even if we have to do a little work in a vineyard to prove it.

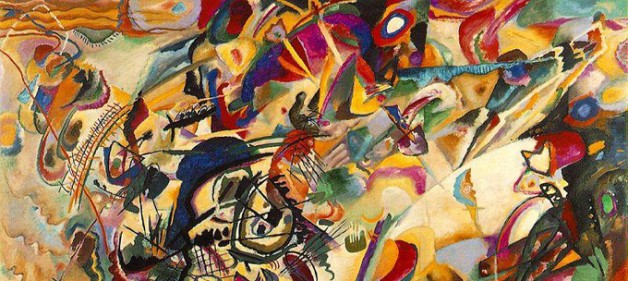

Image: Vincent Van Gogh, Vineyard with a View of Auvers