For many students, we have entered into the season of fatigue. Caffeine doesn’t actually help at this stage; it only delays. Some resort to chewing tobacco. Others buy standing desks. Still others go in for ten-pound bags of unsalted sunflower seeds (autobiographical). At times it can feel like wearing a lead mask underneath your skin, or like your facial features are collapsing around the bridge of your nose. I often find that my morning offerings change from intelligible words to audible groans. My prayers before bed usually include double sleep power (a grace sometimes given for those interested). I’ll even find myself using the old responses for Mass: “It is right to give him thanks and praise. Oops.” Fatigue gets into everything—your food, your prayer, your conversation—making the day into one long waking dream.

At these moments, I often think of how long it will be before I go back to sleep. Napping is out of the question because of sheer time commitment, and so the time between rising and returning to bed works almost like a countdown. What’s even more difficult is when these seasons last for many days, weeks, even months, and time is measured as a slow march towards some far-off future, when we will be delivered from the heaviness of this “present evil age.”

In general, I find looking to the future encouraging. It’s the place of realization. It’s the place of improvement. It’s the place of (please God) priestly ministry for love of Jesus and his people. Looking ahead is indispensable for present preparation, effective planning, and cultivating Christian hope. And yet, the somnolent student’s looking ahead in search of a place of rest can amount to a missed opportunity, a failure of vision, indeed, a false messianism.

In the Gospel of Luke, when Jesus approaches the city of Jerusalem and prophesies the Temple’s destruction, he utters a few terrifying words. With tear-soaked cheeks, our Blessed Lord laments, “Would that even today you knew the things that make for peace! But now they are hid from your eyes [. . .] you did not know the time of your visitation.” Think of Jesus’ contemporaries to whom he addressed this plaint. Beset by their fourth lot of serial occupants, the Jews of Jesus’ day were starved for deliverance. Since the Exile, they had only briefly been reinstated in the promise made to their fathers. Land, descendants, and blessing can only satisfy so much when held on an overlord’s terms. With accumulated frustration and a genuine movement of messianic hope, the Jews of the first century “raised their eyes to the hills” from whence they sought their help. And yet, in the time of its visitation, many failed to recognize their Deliverer, because he did not come according to their specifications.

For the overwhelmed student, it is seductively easy to think of deliverance according to similar false specifications: the sudden cessation of academic demands, or happiness as given by summer vacation. But I fear that such a practice eventually warps our understanding of heaven, as if it were simply the perpetual abeyance of earthly suffering, outfitted with a (well-rested) glorified body and no expectations. Where, then, is Jesus in the picture? And how am I preparing to live with him for all eternity?

In the time of our own academic occupation, the “enemy” of papers, projects, and comprehensive exams has occupied our land, and only once the last pen stroke is jotted can we hope for a new lease on life, a deep exhalation, and perhaps the return to average-sized bags under our eyes. But what if the present is indeed the time of our visitation? What if Jesus is saving me now in this small suffering?

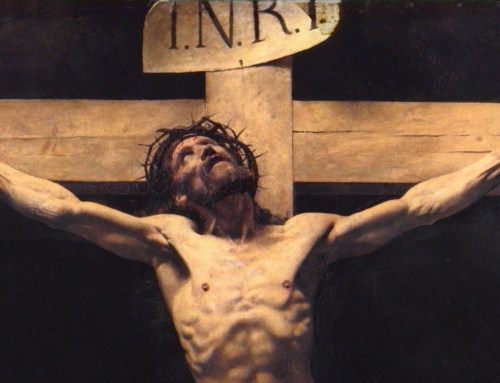

I believe that Christ accompanies and strengthens us amidst difficulties. At times, it can be harder to access this truth, seeing as our normal way of being recollected (sitting down in prayer) is hampered by distractions or the fear of falling asleep. But even still, Christ is loving me now, accompanying me now, and offering overtures of love at the bottom of each coffee mug and the top of each checklist. “Draw near to God and he will draw near to you.” In the midst of trial, a mere mention of the Holy Name can introduce a sacramental vision to the drudgery of work. Christ suffered that we might never be alone in our own sufferings and that ultimately we might discover that all past time was a joy, for it was time spent with him.

✠

Photo by nikko macaspac