“Bertie,” said Bingo reproachfully, “I saved your life once.”

“When?”

“Didn’t I? It must have been some other fellow, then. Well, anyway, we

were boys together and all that. You can’t let me down.”—P.G. Wodehouse, “Jeeves in the Springtime”

Many different types of relations are established at a school. Some of these are transitory: teacher to student, prefect to prefected, bully to bullied, dean to deanery. For these, the character of the school has a dramatic effect on the longevity of the relation: if the headmaster or principal is worthy of being respected rather than feared, or if the teacher offers wisdom and not sophistry, the student may develop an enduring filial piety; likewise, if the bully or dean is not just incompetent but cruel, the relation may perdure under the aspect of a resentment that long outstrips the earthly pilgrimage of the perpetrator.

Other relations established by a school are of their nature more permanent. Knowledge, if it happens to be gained at all, will remain with the possessor. This is particularly true, not of facts, but of the view of the world instilled by a noble education.

One of the most important relations that endures, however, is friendship. In a Christian school, this has three aspects: friendship with God, friendship with teachers, and friendship with one’s fellows. Friendship is first established by spending time with the friend, learning his ideas, enjoying his company.

With respect to God, friendship initially requires a certain discipline in the student’s external actions, but if he cannot move beyond external obedience and make an internal offering of himself to God, there is little hope that the relationship will endure past the time of his schooldays. Thus, a servile or childish attitude of enforced piety must give way to either generous friendship or else indifference or resentment once the binding force is removed. Some students may be blessed with a genuine love of God early on, but for many a gradual transition must take place, a transition from attending Mass because their parents make them to attending Mass because they want to spend time with their friend, Jesus.

With respect to teachers, we should recall that teaching is a species of friendship, but one of inequality, which, if it is to last a lifetime, ought to move towards the equality of true friendship. There may always be a gratitude and piety on the part of the student, but unless the disparity gradually gives way to equality, one might call the teacher a guru rather than a true teacher.

In addition to these two types of friendship, friendship with one’s fellows is a constitutive element of education. Friends are brought together initially by the external circumstance of growing up in the same place, or being sent to the same school. Their meeting may seem random, but like the master who sends out two servants on separate errands to the same place at the same time, the Lord who inspires all that is good within us seems to inspire also the gift of friendship by bringing together his servants in a school of his service. Aquinas says somewhere: “Although a thing’s becoming may depend on another, yet when it is in being it no longer depends on it, just as a friendship brought about by some other may endure when the latter has gone.”

Friendship is initially occasioned by proximity, but if it is true friendship it will endure past this initial period, when the thing that brought the friends together is no more — whether in itself, such as a school closing, or in relation to them, as when they graduate.

In the case of a true friend, even when we are separated by the exigencies of this world, we may still look forward to the day when we might touch the happy Isles, and see the great Achilles — or Bertie — whom we knew.

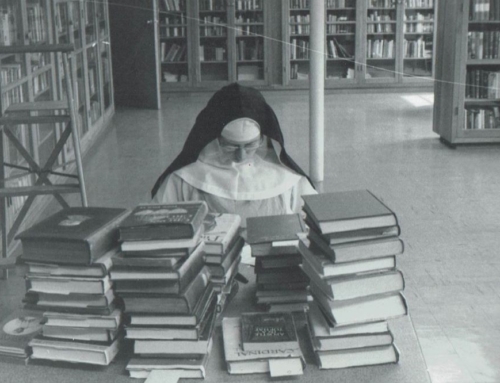

Image – Icarus, St. Gregory’s Academy and Demesne