While thumbing through my great-grandmother’s copy of St. Thérèse’ Story of a Soul last December, I found she had inscribed the following onto the endpaper—two passages, one from Thomas’ Summa Theologiae and another from his Summa Contra Gentiles:

The action of the intellect consists in this—that the idea of the thing understood is in the one who understands while the act of the will consists in this—that the will is inclined to the thing itself as existing in itself. Therefore, good and evil which are objects of the will are in things, but truth and error which are objects of the intellect are in the mind [ST I q. 82, a. 3].

Although we know very little about the loftiest things, the little that we do know about them is more loved and desired than the most exact knowledge that can be had of inferior things [SCG I, ch. 5, 5]. – St. Thomas

As a Dominican in formation, I was elated that my great-grandmother would employ the Common Doctor to illuminate the Little Flower. Still, I wondered: why append these quotations to Story of a Soul?

Both passages describe how knowledge relates to love. By knowing something, the knower in a way receives what he knows into his mind, but by loving, the lover goes out to the beloved. Furthermore, while we can know a lot about what is inferior to us—animals, plants, stars, and the world around us—we know very little about what is loftier than us: God and the angels. Yet the little knowledge we do have of God and his angels should provoke a greater love for them than any knowledge of the material world would do. Indeed, loving God is what makes us supremely happy.

For my great-grandmother, this response to “little knowledge” must have illuminated what was happening in Thérèse. Upon receiving the Word, Thérèse went out to meet Christ in love, much like how Mary responded to the little knowledge of our Lord given by her sister: “[Martha] went and called her sister Mary secretly, saying, ‘The teacher is here and is asking for you.’ As soon as she heard this, she went out to meet him” (Jn 11:28-29). Similarly, the little Thérèse knew of our Lord prompted her to flee the world and live a life in loving contemplation of God.

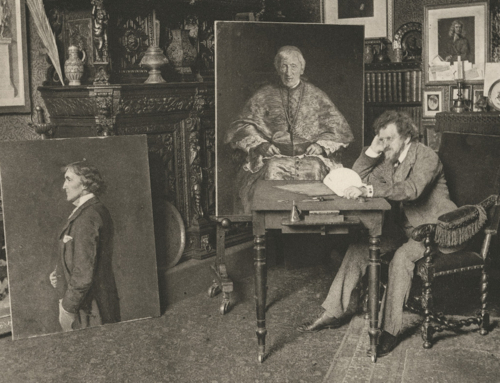

But perhaps, Thérèse—understood in this way—also illuminated what was happening in Thomas. He too had little knowledge of God. While through his study he knew much more than did most human beings this side of the grave, he knew infinitely less about God than God knows about himself. Thomas famously said to Bl. Reginald at the end of his life, “I cannot do any more. Everything I have written seems to me as straw in comparison with what I have seen” (Jean-Pierre Torrell, Saint Thomas Aquinas: The Person and His Work, 289).

How Thérèse responded in love to the little knowledge she had is relatively clear when we read Story of a Soul, but this may not be as apparent when we pick up one of Thomas’ works. Uncontextualized, Thomas’ writing can appear arid and devoid of feeling. This might lead us to characterize Thomas as being more of a professional academic than a man responding in love to God.

This characterization, however, is a false one. Thomas’ writing flowed from his contemplative life. Put within the context of his religious life, Thomas’ academic activity was a kind of search for—a clawing after—him whom he loved most. Thomas gazed on what he knew of God as on a “a lamp shining in a dark place” (2 Peter 1:19). Seeking to be with God, Thomas strained himself with all he had at his disposal to know him. Thomas’ works, like Thérèse’s Story, are footprints of his historical search for God.

I believe this “little knowledge” that produced love linked St. Thomas and St. Thérèse for my great-grandmother and helped her understand both saints under a common narrative. God entered into their minds and charted a course to lead both of them to himself. The “little” knowledge had by Saints Thomas and Thérèse, in their respective ways, ferried each of them to God himself.

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)