Today is the annual March for Life and, under normal circumstances, hundreds of thousands of people would be gathering on the National Mall in order to protest the decision of Roe v. Wade. But our current situation is far from normal, and even the March for Life has had to go virtual. Sticking with this theme of unusualness, and contrary to what the title might suggest, this post will not be an argument for why abortion is wrong. Instead, it will focus on a difficult and nuanced aspect of abortion, which, for that reason, is often overshadowed: the moral fault it can involve.

I want to be clear from the outset that I am not judging the spiritual state of those involved in some particular case of abortion. There are many factors that go into determining the morality of any given action. Some of these factors can lessen the gravity of the moral fault, and others can remove culpability all together. Yet despite the complexity of particular cases, we can still learn a lot from considering moral fault at a more general level.

Why? Because as evil as death and suffering is, the moral fault of those responsible for evil actions is worse.

This claim might sound surprising or even harsh. But it’s important to remember that morality is primarily about what actions perfect us, that is, how we attain happiness. Thus, to say “worse” here does not vilify the one who commits the moral fault. Rather, it implies that the moral fault is actually more detrimental to the happiness of the perpetrator than the resulting suffering is to his victim.

But is it true that moral fault is a worse evil than pain suffered, that the perpetrator is worse off than the victim, that it is worse to kill than to die? The answer to all three questions is, “Yes,” and it flows from the very notion of evil as the privation of a due good. Following a line of thought that stretches back at least as far as Plato’s Gorgias, Aquinas explains this point clearly in his Summa Theologiae. Man’s perfection, his happiness, consists in good operation, and this requires a rightly ordered will. Pain, however, merely entails “the privation of something used by the will,” whereas fault “consists in the disordered act of the will” itself (ST I, q. 48, a. 6). Thus, Aquinas argues that fault has the nature of evil more so than pain because “one becomes evil by the evil of fault, but not by the evil of pain” (ST I, q. 48, a. 6).

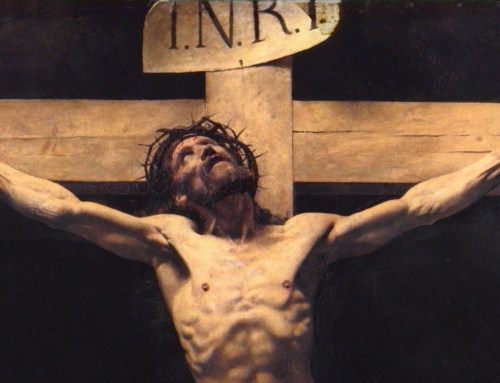

To illustrate this fact, it is helpful to consider the concrete example of abortion. On the one hand, while abortion deprives the child of the good of bodily life, it does not destroy the child’s soul, nor is the child’s will made evil by suffering death. On the other hand, those morally responsible for the abortion, whoever that may be in a particular case, direct themselves away from attaining true happiness by choosing to kill this child, which is a necessarily disordered action. Ultimately, Aquinas’s conclusion that a moral fault is worse than pain suffered should not be surprising. It is essentially the theological formulation of Jesus’s own words: “But I say to you, offer no resistance to one who is evil. When someone strikes you on your right cheek, turn the other one to him as well” (Matt 5:39).

So what can we learn from the fact that a moral fault is worse than pain suffered? Two things: the first relates directly to abortion while the second is more general.

First, the death of a child is certainly a great evil. But when there is a moral fault on the part of those responsible for an abortion, this fault is more detrimental to their own happiness than the child’s death is to him. Thus, love of neighbor should compel us to fight for an end to legalized abortion not only out of love for the unborn but also in order to prevent our fellow citizens from committing actions so profoundly detrimental to their own happiness.

Second, this fact is a timely reminder to all of us that it is never a good thing to commit a moral fault, even for the sake of stopping or preventing some other physical evil. To do so would necessarily lead us away from our true perfection since, to paraphrase Aquinas, we would become evil ourselves by the evil of that fault.

To return to the title of the post, the fifth commandment can certainly be read as, well, a command: “Thou shalt not kill.” Doing so is what provides the basis for most pro-life arguments, which point to the sanctity of life and the violation of the child’s rights that take place in an abortion. But a moral fault is worse than pain suffered, so the commandment can also be read as the loving plea of a Father to his children: “Thou shalt not kill, because doing so will never perfect you as human beings; it will never ultimately make you happy.”

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)