In the Parable of the Vineyard (Mt 20:1-16), there are some who join the harvest at the eleventh hour and others work from dawn to dusk. At the end of the day, both receive the same wage. Likewise, in the ministerial life of priests and religious, there are those who find their vocation as mature adults, and there are others who offer their first fruits to the Lord as young men and women. Through the mystery of providence, people of vastly differing age, experience, and culture are often called to be contemporaries in formation. They have answered the Lord’s call at different moments in the stories of their lives, some as innocent youths and others as aged penitents. In this context, the parable helps to remind us that the young man should not glory in his innocence, nor the old man in his experience. At the end of the day, both will receive the same reward.

Taking a broader view of the parable, we can also consider the time of one’s entry into the vineyard not within the context of an individual’s life, but in the context of the whole history of the Church. Thus, just as in the parable we hear of different hours of the day—the third hour, the sixth hour, and so forth—so, when we consider the history of the Church, we often divide it into different eras. Karl Rahner, for instance, posits three periods: Jewish Christianity, the time between the Council of Jerusalem (A.D. 48) and the Second Vatican Council, and the time after the Second Vatican Council. Other historians and theologians have proposed alternative schema, emphasizing the divisions marked by the Council of Nicea, the excommunications of 1054, and the Council of Trent—to give just one example.

However the ages of the Church are divided, one sentiment that links Christians throughout history is a nostalgic longing for some past era. If only I lived in the age of Faith—or in the flourishing of religious life in the High Middle Ages, or in the Ancien Régime in all its decadence—and so on, depending on my proclivities. At times, these wistful longings can actually be helpful in inspiring men and women of a particular era to imitate the great deeds of past ages. Pope Honorius III, for instance, accounted for the charism entrusted to St. Dominic by writing, “He who never ceases to make his church fruitful through new offspring wishes to make these modern times the equal of former days and to spread the Catholic faith.” And Saint Ignatius, in his turn, reading Bl. Jacob of Voragine’s Golden Legend, was inspired to exclaim, “What if I should do what Saint Francis or Saint Dominic did?”

One perennial source of inspiration has been the scriptural account of the community of the Apostles in Jerusalem (Acts 2:42-47). As M.H. Vicaire shows in The Apostolic Life, many founders of religious orders and movements within the Church seem to have been mistaken in their understanding of the precise historical details of the life of the Apostles, and yet their imaginative reconstructions have borne great fruit in the life of the Church.

In each era of the Church, when the example of the past has transcended mere nostalgia it has also expanded the horizons of the present. Understanding the nuances of Church history frees us from the burdens imposed by the sometimes limited and myopic vision of the present moment. Diligent study of the history of the Church can free us from a naïve idealization of past ages and help us avoid the arrogant assumption that, given our individual sensibilities and preferences, we would have been better off living in a different era. As a matter of fact, the Lord has called us to his service now, at this moment of history, with all of its warts and wisdom. To long to live in a time other than the one the Lord has ordained for us would be to reject God’s providential plan for our lives and for the life of the Church.

In the project of living out our vocations in the circumstances we happen to find ourselves placed in, we can have few better role models than St. Thérèse of Liseux. St. Thérèse entered the Lord’s vineyard not at the eleventh hour, but at the nineteenth, and yet she has received the same reward as the virgins of the early Church, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance. Today, in the heavenly faculty lounge of the Church’s doctors, she engages in erudite discussions with her colleagues, St. Catherine of Siena and St. Teresa of Avila. (At present they only allow St. Hildegard of Bingen to listen in on their colloquies, but she will soon have her turn to chime in.)

And yet, as Thomas Merton once observed, St. Thérèse became a saint without rejecting the bourgeois environment and era that marked her character. However objectionable that culture may have been to Merton himself, he had to admit that one its members, St. Therese, “not only became a saint, but the greatest saint there has been in the Church for three hundred years—even greater, in some respects, than the two tremendous reformers of her Order, St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa of Avila.”

Pray the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest (Mt 9:38)—and if today you hear his voice, harden not your heart.

✠

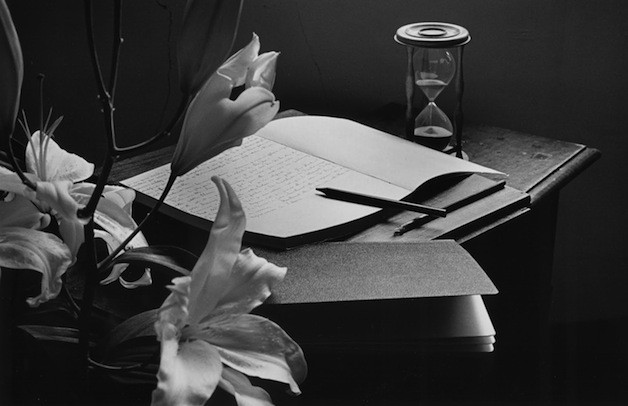

Image: Jean Daniel Jolly Monge, Au carmel de Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux