When the liturgical year winds down, the readings at mass focus on the Last Judgment and the end times. These subjects traditionally provoke mystique and fear. The biblical imagery depicting the end of the world is vivid and sometimes even bizarre.

On the one hand, the prospect of the Last Judgment and the end of the world should arouse a holy fear and awe. This world will not last forever. We will ultimately have to give an account of ourselves about either how grace has transformed us so that we love God above all things or how we have refused grace and preferred other things to God.

On the other hand, we should lend some thought to the Last Things—Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell—because they should affect how we think of the world right now. One way to hone this discussion is to raise the question why God created the world in the first place. God is perfectly good and happy. Not only does he not need anything outside himself to make him happy, but nothing can make him happier than he is. In other words, God cannot benefit at all from creating.

This raises a difficulty because, if everything is done for a reason, God does not seem to have a reason to create the world. This leads us to the idea that God’s goodness is diffusive. In other words, God wishes to see his goodness flower not just in his own life but also in something that is not God. Being perfect in everything, he does not benefit from creating. Rather, he creates the world—something that is not God—so that he can pour out his goodness into the world.

God pours his goodness into the world when he creates, but the world doesn’t manifest God’s goodness after the manner of vendors selling goods at a flea market or a yard filled with chimes sounding random notes in the wind. The world isn’t filled with good things without any inherent order or reason. The world in its totality is ordered as a whole to reflect the goodness of God. Instead of randomly sounding chimes, it is more akin to a symphony that coordinates the sounding of many instruments that together evoke some acute human emotion. As a musical piece expresses the emotions of a human being, so the world expresses the goodness of God. The world is ordered, and the goodness that it manifests is greater than any one part. Furthermore, each part of the world—especially the persons in it—participate in the good of the whole.

Finally, as an ordered whole, the world is building up to something. This is the point of the Last Things. The world has been building up to this point ever since it began. The Last Things should give us pause to reflect how much we rely on God’s mercy and how we should pray to persevere until the end, but they should also affect how we think of the world now. All the good in the world—culminating in the triumph of Christ—will come to fruition. The reason for every evil God permitted will come to light. In the end, the mysteries of the present world and its vexations will be revealed, and we will rejoice in God’s goodness that has been manifested in his creation.

Virgil’s Aeneid has a line that reads, “Perhaps at a future time, recalling even these things will cause delight” (I.203). The first reading for today’s mass fleshes out a similar idea but with more clarity and certainty:

Then I saw something like a sea of glass mingled with fire. On the sea of glass were standing those who had won the victory over the beast and its image and the number that signified its name. They were holding God’s harps, and they sang the song of Moses, the servant of God, and the song of the Lamb:

“Great and wonderful are your works,

Lord God almighty.

Just and true are your ways,

O king of the nations.

Who will not fear you, Lord,

or glorify your name?

For you alone are holy.

All the nations will come

and worship before you,

for your righteous acts have been revealed” (Rev 34:2-4).

✠

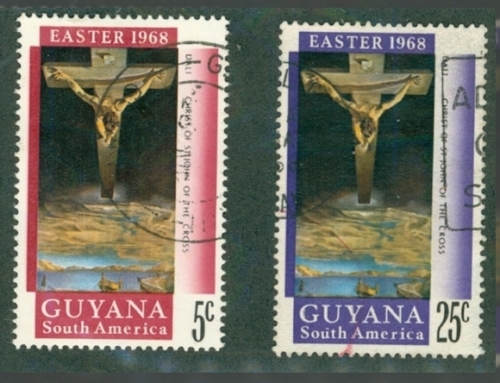

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)