The third in a series considering Jane Austen in light of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas.

Teach us almighty father, to consider this solemn truth, as we should do, that we may feel the importance of every day, and every hour as it passes, and earnestly strive to make a better use of what thy goodness may yet bestow on us, than we have done of the time past.

—from Jane Austen’s Prayers

Northanger Abbey is quite often the most difficult book for the Austen reader to enjoy, as it appears to lack the gravitas that underlies her other novels. Apart from a satirical reflection on the value of the Gothic genre, the novel seems to lack consideration of any serious issue. The language of the novel is replete with playful banter, pointing to the author’s youthful age when she penned the work, and the heroine is extremely naïve. Finally, there is the seeming mismatch of hero and heroine; Catherine Morland is a young and rather silly girl whose only purported source of attraction for the more mature Henry Tilney was “a persuasion of her partiality for him,” suggesting a certain shallowness in the hero. Given such a match, how could the narration of their history be gratifying for the demanding expectations of the avid Jane Austen reader?

In light of the theme of virtue and the stark contrast that Northanger Abbey presents with regard to her other novels, I suspect that the key to getting over many of these concerns lies in a careful consideration of the importance Austen gives to moral education as a source for plot development. From the beginning, the narrator informs the reader that Catherine Morland is a heroine in training and that the course of the novel will follow her education as a heroine. Though playfully framed as the adventures of a Gothic novel, these chronicled episodes of Catherine’s life outline a genuine and sober education in prudence, or practical wisdom. Ironically, by the end of the novel, when Catherine is thrown into truly dire and dramatic circumstances, she acts with such discretion and presence of mind that it hardly even occurs to her, or the reader, that she has finally been thrown into the midst of circumstances that properly befit the stuff of a Gothic novel.

In the four novels (Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Emma, and Northanger Abbey) in which her heroines lack in virtue in some significant way, Austen uses shame as the impetus for the moral reform that in large part leads to the resolution of the novel. Marianne is ashamed of her carefree openness to Willoughby; Elizabeth regrets her prideful disdain for Mr. Darcy and imprudent trust in Mr. Wickham; Emma rues her callous treatment of Miss Bates and meaningless flirtation with Frank Churchill; and, of course, Catherine cries and laments over her naïve and unfounded suspicion of General Tilney’s character and her bold liberty in snooping about a house in which she is a guest. Each of these heroines experiences proper shame in seriously reflecting on her behavior, and each subsequently resolves to amend her character by acquiring the habits that would counteract the foolhardy inclinations that had previously led her into such folly. In contrast, the absence of shame tints the behavior of many of Austen’s antagonists; it is her shameless that shocks and disgusts Lydia Bennet’s sisters, who observe that “Lydia was Lydia still; untamed, unabashed, wild, noisy, and fearless.”

Such a role for shame in the moral education of a young person can be found in Aristotle, as well. Shame holds an interesting position within Aristotle’s theory of human action. As he describes it, it is more like a pseudo-virtue because it is not fitting for the virtuous person to experience fear of disgrace due to incorrect actions, since the virtuous person would have behaved in a proper fashion. He observes that shame “is not becoming to persons of every age but only to the young…because, living according to their emotions, many of them would fall into sin but are restrained by shame.” In other words, shame is conducive to the end of a young person’s growth in virtue and belongs to the virtuous person hypothetically; that is, if she were to commit an unvirtuous act, then she would experience shame. Aristotle maintains that it is ultimately a matter of practice and repeated experience of shame due to failure that a young person manages to grow in virtue. Thus, shame and activity are indispensable features of a moral education.

On this last point, it is interesting that in each of Austen’s novels, the critical moments of each heroine’s development occur in the midst of activity, particularly travel. Even Emma Woodhouse, who has rarely ever left her father’s side, receives Mr. Knightley’s chiding remarks during an outing to Box Hill. It seems that at least implicitly, Austen agrees that an active life is conducive to the development of virtue. So there is more than just a semblance of truth to the narrator’s ironic claim in Northanger Abbey that adventure is a necessary component in the education of a young woman. Through her adventures in Bath and at Northanger Abbey, Catherine learns how to apply the good principles she has already learned and how to properly esteem the variety of characters and behaviors in the world.

Normally in Austen’s novels the heroines are not the only students of virtue, but each of their heroes is, as well. For example, Mr. Darcy must learn to temper his pride with amiability before he can gain the respect and love of Elizabeth as he ought. On the other hand, Henry Tilney appears to be rewarded for merely feeling a sense of gratification at receiving the attentions of a pretty young woman. Nevertheless, Henry does not get the satisfaction of marrying Catherine directly after he expresses his intention. Catherine’s parents insist upon waiting for his father’s approval, which he did not receive until the end of a rather anxious series of months. Moreover, the narrator intimates that such a period did a great deal of good for Henry, as well as Catherine, by “adding strength to their attachment,” hence the rather enigmatic closing of the novel: “I leave it to be settled by whomsoever it may concern, whether the tendency of this work be altogether to recommend parental tyranny, or reward filial disobedience.” Catherine is not the only one who must grow more mature in order to ensure her happiness, but Henry must also establish firmer foundations in his regard for Catherine, which can only be done through a more thorough knowledge of her character. With this prolonged period of engagement, Catherine gains more time to grow in virtue and Henry receives the opportunity to become better acquainted with Catherine’s character. In this way, they become more suited for the type of virtuous friendship that will enrich and sustain their marriage.

✠

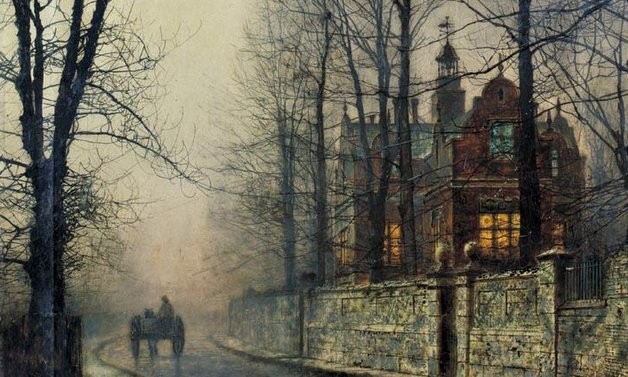

Image: John Atkinson Grimshaw, November Moonlight