As if middle school wasn’t horrific enough, the Netflix series Stranger Things adds an interdimensional monster, a government conspiracy, and a telekinetic “weirdo” (Ch. 2).

Today, they release Season 2.

Foundational to the gripping narrative of the show is what the characters come to name “the Upside Down,” a toxic copy of our world into which the heroes must inevitably venture to save their friend from the terrifying, man-hunting Demogorgon. An enthralling work of fiction, Stranger Things also expresses something true of reality that is worth reflecting on, and the Upside Down is just such an example.

In their dilemma, the team of Mike, Lucas, and Dustin turn to their nerdy science teacher, Mr. Clarke, for guidance on what this “Upside Down” might be and how it might work. He draws his explanation of multiverse theory using a paper plate and a pen: “Well, picture an acrobat standing on a tightrope.” This acrobat, representing us in our world, is limited in the way he can move. But a flea (here the monster) seems to have a much greater versatility; he’s free to go all around the rope, even upside-down. Yet the boys realize that they will need to perform some truly acrobatic stunts to follow the “flea” beyond the limits of the world to rescue their friend Will.

Where this analogy helped the protagonists to track down the gate to the Upside Down in the world of Stranger Things, it can also help us to reenvision our own world with an eye to the the Kingdom of God. The saints, like spiritual “acrobats,” see things supernaturally as from the “God’s-eye” point of view. Their vision is transformed by grace: they look out on the natural world as if they (or it) were hanging upside-down.

He who has seen the whole world hanging on a hair of the mercy of God has seen the truth; we might almost say the cold truth. He who has seen the vision of his city upside-down has seen it the right way up. (G.K. Chesterton, Francis of Assisi, 64)

According to Chesterton, Christians come to see the world in a new light, with a new perspective. For example, he famously depicted St. Francis’ radical reform of life not as a conversion, but as an inversion. The young man’s life was flipped head over heels through his encounter with God:

It was really like the reversal of a complete somersault. . . . It is necessary to use the grotesque simile of an acrobatic antic, because there is hardly any other figure that will make the fact clear. But in the inward sense it was a profound spiritual revolution. . . . He looked at the world as differently from other men as if he had come out of that dark hole walking on his hands. (Chesterton, Francis, 57)

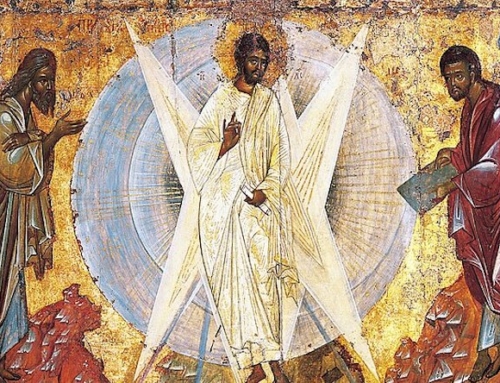

This rather humorous image of St. Francis as an acrobat fits squarely into Mr. Clarke’s tightrope analogy. Depicting St. Francis or the saints as high-flying acrobats manifests the new perspective that one has when seeing the world from the point of view of faith. St. Francis’ new perspective was that of the mystic, whose eyes have been opened to the deeper, invisible realities of the world. Rather than seeing a chilling alternate universe, Francis saw the world around us as suffused with the potential for grace. He realized that God had definitively flipped the world upside-down in Christ’s saving work. So in order to see it truly, we must ourselves be converted or even inverted.

Such is the Kingdom of God, where the first are last, the last are first, and the Master washes the feet of his disciples (Mt 20:16; Jn 13:12-17). May the Lord grant us the eyes to see his grace at work in the world and to let ourselves be flipped head over heels for love of Him. Let us pray that we may be like the disciples of whom it was said,

These men who have turned the world upside down have come here also. (Acts 17:6)

St. Francis of Assisi, pray for us!

✠

Image: Timmy Blue Downside Up by Randy Jacob