This is the first of the series The Summa in Verse.

One of the tragedies of modern education is that many people have read Dante’s Inferno, but few have ascended to the heights of the rest of that great and unified work, The Divine Comedy. Interestingly enough, this unnatural division happened to another of my favorite medieval works, St. Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae. Even more interesting is that The Divine Comedy has often been called “The Summa in Verse,” reflecting the deep understanding of things human and divine in these two medieval cathedrals of writing.

That Dante was influenced by St. Thomas is incontrovertible. Dante was not, of course, a mere illustrator of the thought of Aquinas, and there are innumerable facets of The Divine Comedy that merit serious study: his use of Italian, 14th century history, its place in the genre of epic poetry, and many more. But I would like to propose three ways in which Dante’s magnum opus can indeed be read as an inspired illumination of the Angelic Doctor.

KEEP IT TOGETHER (Don’t cut the tour short)

As I mentioned, the Inferno has merited the bulk of students’ exposure to the great Dante Alighieri. Similarly, there was a time when the second part of the Summa (the section on morality) was sold separately by some enterprising Dominican Friars because of its singular popularity. Unfortunately, this practice led to a separation of Thomas’s moral teaching from its proper context within a well thought out framework.

The treatise on morality is outstanding, but it needs to be seen in the context of the whole. In the first part God is shown in his triune perfection and provides the answer to the ultimate question of the second part (“For what am I created?”, or better, “For whom am I created?”): the supreme happiness of forever beholding the Divine Face. How on earth can I get there, you ask? The third part provides the answer: through God himself, the incarnate Christ come to earth, and through the Sacraments he established.

Likewise, The Divine Comedy can best be understood as a whole. Why then, by reading only Dante’s Inferno, is there this fixation on grittiness and moral choices? I think we know the trials and failures of life all too well, and seeing miserable situations can help us feel better about ourselves. Our fallen nature finds it easier to understand an illicit love affair ending in murder described in the Inferno than St. Bonaventure waxing eloquent about the foundation of the Dominican Order in the Paradiso. But as Dante comes to realize, the reward sought in his adventure is not the Schadenfreude of hell, but rather the awesome sights of heaven that can transform our mundane experience of life. Or, if you ever go to Paris, don’t just take the sewer tour — go and see the soaring Eiffel Tower and the lofty Chartres.

FREEDOM FOR EXCELLENCE (Not frozen in hell)

Americans value our freedom, and rightly so. We sympathize with the radical rebellion of Milton’s Satan, who “courageously” says, “I will not serve.” That’s freedom, right? Doing what I want. Better to reign in hell than to slave away in heaven. Not so, we find out in the Inferno. Unfortunately for Lucifer, ruling in hell involves being frozen solid, chomping on Judas, Cassius, and Brutus. Turns out freedom of choice needs some guidance.

Cue St. Thomas. Human beings are given freedom as a great gift, reflecting the Omnipotent God. St. Thomas describes him as pure act, not confined by anything. When we use our freedom to choose, it is not irreducibly good. The actions we perform in freedom are for a purpose: acting in freedom to be excellent. By moving from the potency of options to the act of performing well according to reason and divine revelation, a human being moves from doing things that develop his nature with difficulty and irregularity to being habituated according to the perfection of his nature. That is to say, by practicing virtue, we promptly, joyfully, and easily do those things that perfect us according to God’s design of the human person. We leave behind the arbitrary (and icy) “freedom” that is an illusion, for the true freedom which lets us whirl, dance, and fly in Paradise. (And is there ever much dancing and whirling in the Paradiso.)

PILGRIMS ON THE WAY (If you’re going through hell, keep going)

Much has been made of the road map of the Summa. It starts with God (infinitely perfect and blessed in himself), moves with his free act of creation down to earth, makes a big detour in sin, and hitchhikes with Christ to get us back on track to eternal bliss in heaven. That which God makes proceeds from him and should return to him.

Dante begins his tour in the dark wood of middle age. This puts us in the middle of Thomas’s road. He descends through the harrowing and horrifying account of sin and then…that’s it.

It shouldn’t be, but it is if the reader stops there! I felt filthy after climbing with Virgil down through the more graphic and stomach-turning tortures of the damned. The beach on the outskirts of purgatory felt like a cool drink of water after a run on a hot day. The spiritual analogy is clear: stopping in the hell of our lives leaves us like Judas. All men have sinned, just like he did. But if he had kept reading, he wouldn’t have ended in Dante’s hell — he would have found Christ anew and joined the Good Thief and St. Peter the denier in Paradise. You are what you read.

And so, I dare you, dear readers, to join us this week as Br. Gregory tells us about how the Inferno artistically depicts the mess that results from rejecting the order established for our benefit by God. Ascend Mt. Purgatory with Br. Edmund as guide, purifying and remaking us for the Kingdom. Listen as Br. Mannes reveals to us why it is, after all, just so hard to read the Paradiso. Then sit back and relax as Br. Boniface (not named after Boniface VIII, thank goodness) tells us what we’ve learned this week. Be brave; read through the whole Dominican Comedy.

✠

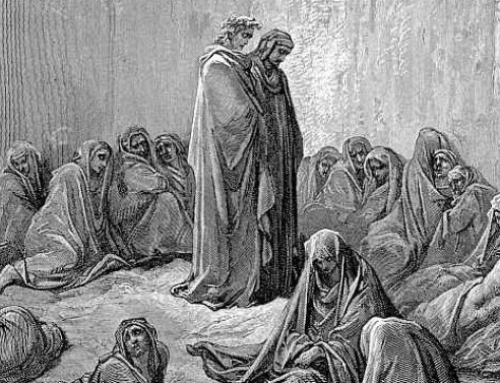

Image: Salvatore Postiglione, Dante and Beatrice