The Star-Spangled Banner displayed permanently in the National Museum of American History is one of the most extraordinary artifacts of our nation’s first century. The Star-Spangled Banner, also known as the Great Garrison Flag is the flag that flew over Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore in 1814. It was this flag that inspired Francis Scott Key’s poem, which became our national anthem. The flag prominently lies in its own exhibit, but in order to view it visitors must first traipse down a lengthy corridor filled with flag-like memorabilia before reaching the monumental banner itself. The exhibit is only dimly lit, so as to protect the flag, and consequently the walk to it is guided by modest and gentle light. Then suddenly the stroll down the narrow hall ends and the viewer rounds the corner to face one of the most impressive monuments of American history.

The flag, awe-inspiring as it is, has the remarkable power to take Americans beyond themselves and to allow them to enter, if only for a second, into something greater. One can actually see this happening during a visit to the exhibit. Museum guests stop in their tracks as they turn the corner of the corridor, their eyes fixate on the marvelous stars and stripes before them, and they become lost, as if they were taken up into the very winds and sands of time. The Star-Spangled Banner therefore is much more than a sight one simply takes in; it acts as a vehicle which transports its spectators to concepts richer than the sum total of their immediate sense impressions.

The Star-Spangled Banner acts as a medium that elevates the minds of men. Why? After all, it’s really nothing more than old fabric stitched together in a multicolored pattern. Arguably red, white and blue do not even make the most evocative or handsome color scheme. To those who gaze upon it, however, the flag is something more than just a flag. It’s a symbol, and as a symbol it does more than just represent the United States. For those who allow the flag to seize them, the flag actually makes present to them not only the realities of a distant past, but also transcendent ideas like patriotism or the American Dream.

All of this happens on a natural level. Visiting, seeing, and experiencing the flag are actions one does. The flag, operating as a sign, manages to make additional realities present to its viewers. Although an exalted experience, such an event is not supernatural. Men often encounter historic artifacts that are signs pointing to something other than themselves. Signs and symbols are part of the natural order.

A thing like patriotism, however exalted, is not enough to fill the human heart. The mediation on the Stars and Stripes takes a person beyond himself, but not far enough for him to be happy. The Christian implicitly knows this. The Christian also knows that signs and symbols, indeed all natural things, become radically changed with the mysteries of Jesus Christ’s Incarnation, Death and Resurrection. Material things, once bound and locked away by the fetters of man’s sin, are opened anew in Christ. Jesus Christ, Lord of all creation, will now use signs and symbols as vehicles of His grace to even more glorious ends. A Christian no longer lives limited to those concepts represented by the signs of the natural order—even one as marvelous as the Star-Spangled Banner.

Even the best of temporal goods, like patriotism, pale in comparison with the grandeur of our Triune God. Our God is an infinite reality, exalted and glorious far beyond measure. He fills the longings of our hearts with more powerful means than even earth’s highest goods. God is an eternal communion of love who bids all people to come and share in His joy. We can and do enter into this love, if only temporarily and imperfectly on this side of heaven, if we behold the signs He gives us. In this way a humble bow of the head before a crucifix or a tender touch of a rosary can seize the soul and usher the heart across the borders of this world.

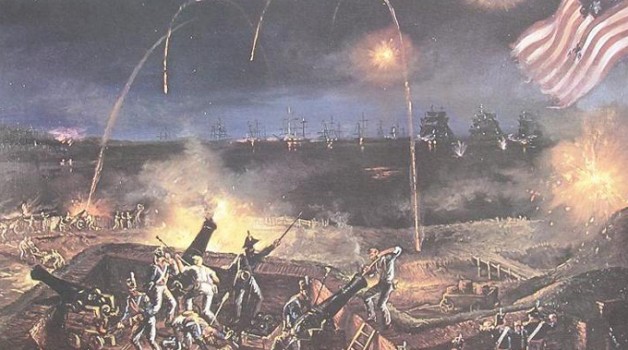

Image: Battle at Fort McHenry