The heart changes the countenance,

either for good or for evil.

The sign of a happy heart is a cheerful face. (Sir 13:25-26)

And the sign of disappointment? A frown. Of embarrassment? Blushing cheeks. Of pain or anger? Clenched teeth. What about profound sadness? Teary eyes. And what is the sign of roaring merriment? A mouth open with laughter.

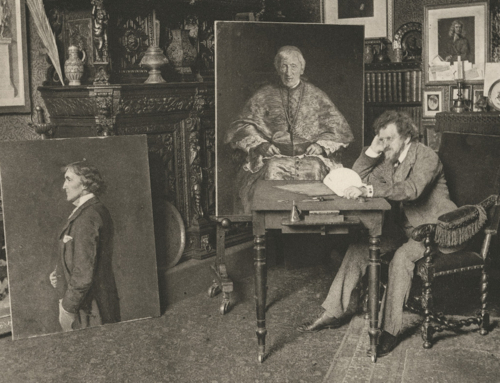

A saintly face, then, manifests a saintly heart. What do those look like?

In a beautiful paragraph at the start of The Quest Elisabeth Langgäser writes:

Let us . . . examine the face of Mother Cabrini, the first saint of North America. Let us look at it honestly and without fear, this quiet, sublime countenance full of kindness and gentle humor. It is broad and plain, like the face of an Italian peasant woman, with big black eyes that are sheer love. The mouth too is large, an animated mouth whose corners curve slightly upward; a mouth made as if made for merriment and for storytelling. The cheeks are full. They are ripe and like fruits that must soon be picked. Here and there is a faint shadow – the shadow of a mystery. For the flesh of a saint harbors a secret that is fearful and repulsive. It was crucified and hammered into ripeness by the fists of Satan. In the battle with the Adversary it has already been touched by decay, already carries the mark of death and has become an object of horror to the world. But also it has already passed beyond decay. It has already survived its death and is on the point of manifesting in itself immortality and the resurrection of the dead.

On Mother Cabrini’s face, on the face of any saint, contraries meet: silence with storytelling, recollection with laughter, sublimity with commonality, light with shadow, youth with decay, death with resurrection. The saints’ flesh, their faces, carry opposites because their hearts do too. In unredeemed nature, these contraries would wound flesh, disfigure faces, and rend hearts irreparably, to the point of destruction. For contraries do not abide together so easily. One opposite could dominate over the other so that a face becomes a caricature. Or two contrary dispositions might be in a person, which almost splits him into two, such as Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde. Or, out of fear, human qualities could be so muted that a person becomes bland and expressionless.

But the saints hold contraries together in a harmony of paradoxes revealed even on their faces. They can do so only because their hearts were transformed by (even into) the heart of Christ Jesus. This heart knew sorrow and utmost joy. It felt anger and compassion. It was pierced and resurrected. We wonder at the saints, their flesh, their faces, their hearts, because they were, and will be once more at the resurrection, one with Jesus’ flesh, face, and heart. And the human heart of Jesus is one with the heart of God; on his face we see God’s face.

✠

Photo of Francesca Cabrini