This is the third of our series The Summa in Verse.

Dante’s Purgatorio graphically illustrates the principles of St. Thomas’ treatise on the moral life (the enormous Secunda Pars of his Summa Theologiae): in living the life of the theological virtues by God’s grace, human beings become ever more free. Purgatory is not a grim torture chamber, but rather a place marked by hopeful suffering and ever-greater freedom. Classically, those who are in Purgatory died with God as their final end (i.e., with sanctifying grace in their souls); they simply need some additional preparation and refinement before they can live well the life of Heaven.

The chief mark of those Dante meets in hell is their stasis: These poor souls stagnate in their sins. Those in hell are inevitably terrible bores. Much like Queen Orual’s “complaint against the gods” in C. S. Lewis’s novel Till We Have Faces, the manifesto of the damned is a nasty, brief scribbling written out and recited over and over again. And they died proclaiming it to God and to their fellow men.

By contrast, those Dante will meet in heaven are fully and finally free: moral virtuosos. They have acquired God’s perspective and put petty setbacks and trivialities in their proper place. The saints have become like the One they loved on earth, and as a result, they are magnanimous and free for the highest goods. These souls died completely oriented toward God or have already passed through the purgatorial fires, liberated from selfishness and without the slightest trace of meanness. Now, outside the limits of time, their own weaknesses, and the difficulties of their environments, they enjoy God with a perfect liberty.

The souls in Purgatory don’t simply occupy an unpleasant station midway between these two — they are, if you will, in the foyer of heaven. It is a state for those who die bound for heaven, but who are not yet fully free, and thus fully prepared to enter into its joys. But unlike the muddled way of things on earth, there is clarity about the joy sought in Purgatory. St. Thomas is concerned in the Secunda Pars that we fulfill that operation for which we were created. We’d be disappointed in a classicist who couldn’t read Homer or a pianist who only played hot cross buns on the piano; likewise, Thomas is disappointed in the human person who doesn’t live in friendship with the Triune God. Learning how to live with Him and to enjoy the things that he enjoys is the whole aim of growth in the Christian moral life, and Dante displays the nature of this human improvement in the Purgatorio. Time in Purgatory accustoms us to the life we’ll live in heaven.

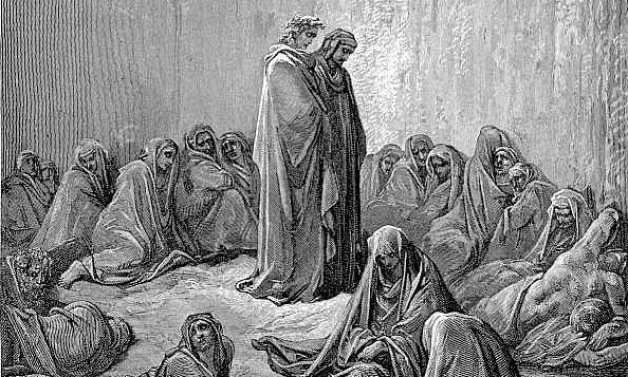

The purging process is certainly a painful thing, and Dante portrays it vividly: The lustful walk in fire, the envious are blinded, and the proud crawl around bent double under huge rocks. But these gruesome punishments are not the fruit of some perverse pleasure. Rather, by these trials the divine kindness reorients those in Purgatory to what they have declared they really want. “We want to see You,” would be one way of expressing the wish of these pilgrims. “Well,” God says, “then you’re going to learn to take your eyes off some other things. And since you’ve asked so sincerely, I am going to show you how to do it.”

Most of us have been initiated into difficult enterprises at least once in our lives. There is a pain in being stretched to a higher plane of life. If you want to beat the Kenyans across the finish line of Boston, you’ve got to wake up early, run lots of miles, and eat properly. And if you want to sing in the heavenly choir with all the saints, you have to learn to sing on key, no matter how many hours it might take.

The whole work of the moral life is driven by hope for the divine goal. It is even more profound than the freedom to read of Sarpedon and Patroclus in The Iliad, to play Vivaldi, to sing the Exsultet, or to smile cresting Heartbreak Hill, because it is our true and ultimate end. Only by being purged of our vices and sins can we attain to that freedom for which we were made.

✠

Image: Gustave Dore, The Envious