The music stops, and all the children feverishly vie for a seat, aware there is one fewer chair than players in the game.

Brother and sister race through the parking lot to the family minivan, their frenzied cries of “SHOTGUN!” having proven too inconclusive to definitively award the sole front passenger seat to either claimant.

Two coworkers interview for the same promotion, knowing there is only one open seat at the all-important boardroom table.

In these three cases, the ideas of seats and possession are linked. Etymologically, the verb “to possess” comes from two Latin words: potis (able) and sedere (to sit). To possess something quite literally means being able to sit in a particular place legitimately and have our actions flow from this point of authority.

A person may have a certain seat—an occupation, an office—from which he or she derives power and responsibility. This is brought out today in the Church’s liturgy. We celebrate the Chair of Saint Peter, the figurative seat from which all popes down through history have shepherded the flock of Christ. We alter our focus momentarily away from the flesh and bones of the man in order to acknowledge the point from which his authority flows. This is a good exercise to do sometimes, mindful of our Lord’s declaration: “You are Peter, and upon this rock (seat) I will build my Church.”

This recognition is freeing and demands fidelity. While we ought to have respect for a pope because he is a priest of Jesus Christ, we do not have to concur with everything he may say. As Father Urban reassuringly tells a crowd of believers in the J. F. Powers novel Morte D’Urban, “If any of you people should happen to be in Rome, and you hear the Holy Father say he believes it’s going to rain, you don’t have to believe it—no, not even if you’re a Catholic.” What our faith does require is that we be unwaveringly obedient to thought-out teachings on faith and morals that he gives ex cathedra—from the seat of his authority, from the Chair of Saint Peter.

The concept of authority flowing from possession can also be applied to our own action. We are created by God to be self-possessed creatures: men and women who have a seat within ourselves from which we act with authority and accountability. But it is in living out a life of grace through self-possessed actions where one finds that the fulfillment of self-possession is not reached autonomously. Rather, it is achieved with the aid of Christ who inwardly dwells in the soul, who is able to sit in the seat of the soul and vivify it with his life-giving presence. How different this is from aimlessly wandering amidst the broad roads of the worldly, along which we will surely encounter the one who has been deposed from his natural seat among the angels and now prowls about like a roaring lion, looking for someone to devour, someone to possess (1 Pet 5:8).

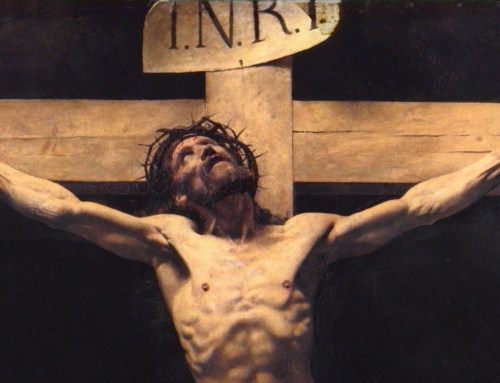

The self-possessed person is paradoxically he who is possessed by Another, by the One who possessed a seat upon Calvary’s hill in the form of the Cross. Perhaps this is why the road to self-possession is so often a via dolorosa. Christian philosopher Kenneth Schmitz writes, “the Christian journey inward is taken for the sake of a salvation that exceeds the self’s grasp. Moreover, Christian interiority begins not so much with flight from the world as it does with self-examination, self-purgation, and self-denial” (At the Center of the Human Drama, 137). The road to self-possession is a narrow road by which we must learn to sit in purifying silence and contemplation, through which we are more deeply united to Christ within us. In this endeavor, St. Augustine’s description of his own transformative experience may serve as a light to our path:

Urged to reflect upon myself, I entered under your [i.e., God’s] guidance into the inmost depth of my soul. I was able to do so because you were my helper. On entering into myself I saw, as it were with the eye of the soul, what was beyond the eye of the soul, beyond my spirit: your immutable light…You were within me, but I was outside, and it was there that I searched for you. In my unloveliness I plunged into the lovely things which you created. You were with me, but I was not with you. Created things kept me from you…You touched me, and I burned for your peace. (Confessions Book X, Chapter XXVII)

✠

Image by Sayan Nath