This is the fourth of our series The Summa in Verse.

Thinking is hard work, especially when it’s about lofty and abstract things. It’s the last thing that comes to mind when we want to relax. More typically, we take off our shoes, stretch out on the couch, and put on a mindless movie or television show. Modern man asks: why put forth effort in reading poetry or a lengthy novel when there are people in Hollywood who dedicate themselves to our service? They create scenes that overflow with action, drama, and emotions, and our only responsibility is to sit back and soak it in like a king who sits back and opens wide his mouth as his servants feed him grapes.

It is our desire for quick and easy gratification that causes us to spurn reading, especially books that place great demands upon our minds. Dante’s Paradiso is no exception. Many brave souls who venture into Inferno and conquer Purgatorio halt before the high and mighty Paradiso. Arguably, it is the least read and least popular of the three books. The very subject matter causes this difficulty. After all, how is Dante supposed to portray what eye has not seen and ear has not heard (1 Cor. 2:9)? Sin and purification are easy for us to understand, but the life of glory to come is something none of us has fully experienced. Just as our experience of confession and seeking forgiveness aligns with the souls being purified in purgatory, so too do our experiences of the physical world align with the mountains, lakes, and cliffs in the first two books. But because we cannot comprehend the fullness of beatitude in Paradise, it would be an injustice to describe Paradise in ordinary terms. Instead of mountains and lakes, Dante is led by Beatrice through the heavenly spheres, is seemingly transported between planets, and instead of seeing men walking on the ground he sees human souls as lights whirling around a Great Light. I for one don’t encounter talking whirling lights on a regular basis.

So why undertake this arduous journey that strains the mind? Why not just be satisfied with the first two books, or — better yet — wait for Hollywood to make a movie for us? Aside from simply being able to say you’ve read the entirety of the Divine Comedy, the Paradiso gives purpose to the first two books. Sinners are punished in the Inferno and men purified from attachment to vice in the Purgatorio. But why are these two books not enough? Aquinas teaches us that every creature has a purpose, an end, a goal to which all actions are oriented. For man, happiness is the goal that guides every action. There is nothing that we do because it will make us unhappy. The problem is that while we all want happiness, we struggle to determine what exactly constitutes happiness. On the one hand, there is a temporary happiness in the pleasure of eating a piece of chocolate cake and, far worse, there appears to be a happiness that derives from sinful actions. But, we know that not all happiness is the same — some joys are only apparent and short-lived.

As Christians we know that the true happiness that satisfies consists in knowing and loving God, and ultimately doing so in the beatific vision in the life to come (ST I-II, q. 1, a. 8). Dante writes of the beatific vision: “Before that Light one’s will to turn is spent: one is so changed, it is impossible to shift the glance, for one would not consent, Because all good – the object of the will – is summed in it, for it alone is best” (Paradiso 33. 100-104). It is this vision to which we are called; it is the attainment of beholding God, through the power of his grace, that must guide our actions. We don’t climb mount Purgatory with Dante simply to reach the mountain top. Our purpose isn’t just to be morally virtuous. Our purpose, our end is to behold God. Only in realizing the beauty and satisfaction of Paradise can we understand the horridness of Hell. Only the hope of Heaven grants willingness to men to suffer joyfully in Purgatory. Without this hope and knowledge, Purgatory would be sheer torture.

This end for which man is made is quite different from the end of the souls described in the Inferno. Dante writes of Paradise, “This kingdom free of care and filled with joy, crowded with citizens of the Old and New, turned all its love and vision to one goal. O great delight that glittered for their view” (Paradiso 31. 25-28). Christ offers us true freedom and true joy. Unlike Satan, who is helplessly frozen in a sheet of ice and stuck for all eternity with himself, the souls of Heaven are free in Christ. There is no heavy ice in heaven, but rather the souls fly about the “great delight that glittered their view.” At present we cannot fully realize it, but those in heaven are the least boring. Sin repeats itself and turns a person in on himself. But the life of grace sets us free, draws us out of the heaviness of sin, and constantly fills us with the beauty of the One who is ever ancient, ever new. Reading the Paradiso then is a necessary and noble attempt to glimpse the greatness of the promises of Christ. Knowing the goal not only guides our reading of the Inferno and the Purgatorio — it plants the desire in us for the grace of repentance that leads to the Kingdom of Heaven.

✠

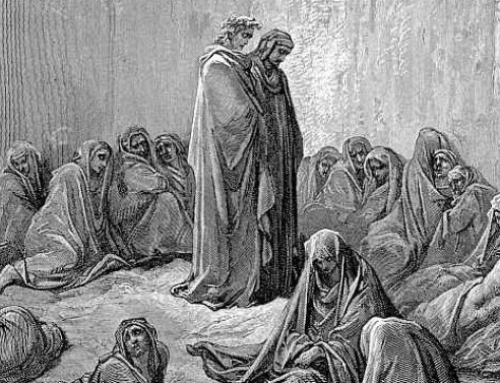

Image: Philipp Veit, The Heavens of the Blessed and the Empyrean