Many Saturday evenings at the Dominican House of Studies, you will find a group of student brothers gathered in one of the basement rooms watching an episode of Hercule Poirot. Part of the enjoyment is guessing who actually perpetrated the crime. I enjoy mysteries and grew up reading Perry Mason novels and the stories of Sherlock Holmes. The creators of these famous detectives approached their description of the mystery in different ways. Erle Stanley Gardner pointed many of the clues to Perry Mason’s clients, while Agatha Christe cast clues that implicated everyone—and for Murder on the Orient Express, it was indeed everyone who participated in the murder.

This is what makes mysteries so attractive – trying to find out who did it, something that even these great detectives did not always accomplish perfectly. Holmes admits to being outwitted two or three times, most famously by the woman, Miss Irene Adler, in A Scandal in Bohemia. Poirot also admits to two or three mistakes. Perry Mason had a better record, with no client ever convicted in the novels, despite the bizarre circumstances of The Case of the Terrified Typist.

One of the reasons why these fictional detectives are so successful is that they see things differently than the reader or audience. The reader/viewer and the detective both see all of the clues presented, and only when the story is written badly is there some clue that is kept hidden until the end. In fact, Poirot issues this very complaint against a stage production of a murder mystery in the TV version of The Third Floor Flat—the critical clue was not released until the very end of the performance. Ordinarily, the information is there for all to see even if its significance is not yet known. It takes the mind of the great detective to put everything in order. After all, there is only one sequence of events that will account for every clue.

The primary way these three detectives are able to combine all the clues successfully is through silence and inaction. Certainly, all three are active investigators who like to see the crime scenes first-hand to ensure they see all of the evidence and even to set traps for the perpetrators. However, they understand the need for not acting as well. Mason would sit at his desk long hours into the night on some cases, just thinking. Holmes will spend an afternoon at the museum because he knows that nothing more can be done until a later time. Poirot once angrily responded to a client “Hercule Poirot will act when Hercule Poirot needs to act!” There is no need to act all the time. By stepping back, the detectives are able to put all the clues in their proper place.

This method of the great detectives is also appropriate to our own lives as we contemplate the mysteries of God. From the early years of the Church, people have fled the bustle and distraction of the cities to live lives that permit them to spend much of their life in silence to get to know God better. Poirot and Holmes both disliked the countryside, preferring the city with all its action. However, they were able to carve out niches of quiet so they could successfully solve the cases presented to them. Religious orders that developed in the cities have their own structures to ensure time for silence. The Dominican Constitutions, for example, require thirty minutes of meditation each day. It can be a great temptation to let this time with God go because there is so much active work to do. However, without this time of silent prayer and meditation, we would lose the ability to see how God is at work in our lives and our world.

As all metaphors have limits, a word of caution about our fictional detectives is necessary as well. Despite, or perhaps because of, their great minds, these detectives are prone to vices. When there is nothing interesting to engage his mind, Poirot whines that his grey cells are dying and he can no longer function as a detective. Unless actively engaged in some intriguing mystery to solve, Holmes often lies in opium-induced dreams, trying to escape what he perceives as the monotonous boredom of everyday life. The action of each case is its own end and does not point to anything beyond.

For us, however, God is far above us, far beyond us, and thus we can neither find all the clues in creation nor put together a complete picture. Therefore, we must slow down our busy lives each day in order to contemplate that which we have seen and experienced so that we might arrange them in their proper order. Only then can we come to know God a little better and thus know how we are to act.

Saint Columbo, patron of detectives, pray for us.

✠

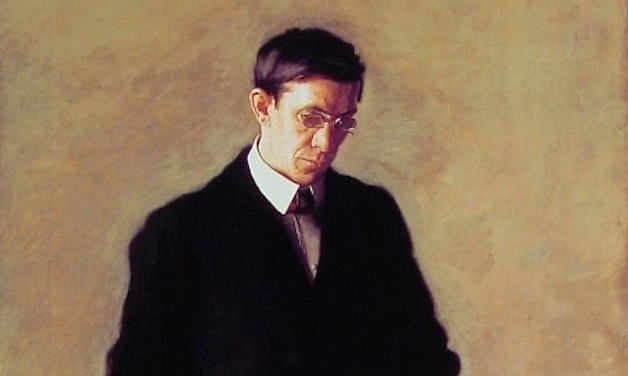

Image: Thomas Eakins, The Thinker