Girolamo Savonarola was born in Northern Italy in 1452 to a well-to-do merchant family. Growing up, he was taught a love for the moral life and a hatred for decadence by his fervently religious grandfather. At the age of twenty-three, he abandoned all the vanities of the world to give himself to God alone, leaving home to become a Dominican friar. He was known to be fervently observant in his religious life, and from this personal holiness flowed a preaching that captivated all hearers.

He was soon brought to the great city of Florence at the request of the ruling Medicis. All were amazed by his gift of prophecy. In particular, he prophesied disaster in the republic of Florence. Though Florence was one of the more prominent cities of Europe at the time, when Charles VIII of France was making his way toward the republic, the citizens began to take Savonarola’s prophecy seriously. One might attempt to credit his prophecies (and there were many) to political savvy, but there was always something too vivid and concrete about them; at the very least, his contemporaries learned to trust him.

Savonarola was sent as an ambassador to make an agreement with Charles VIII to prevent the otherwise almost certain sack of Florence. After this success, trust in Savonarola was so great that he was able more or less at his will to write up the new constitution for a democratic republic. He even was able to go so far as to plea, successfully, for peace toward the friends of the old Medici government. The few years of his influence are something of an eloquent testimony to the power of the word of God to create and sustain peace in a troubled world.

Unfortunately, he had powerful enemies. The allegiance of Florence with Charles VIII was disadvantageous for much of Italy, but this was not Savonarola’s greatest obstacle. He preached against moral depravity in an emerging decadent renaissance society. He feared no man in his call for the pursuit of the Christian ideal. This made him enemies, both at home and abroad. Because of his popular appeal, it was difficult to have him removed. At the same time, for every moral reform he successfully enacted in society, his enemies became increasingly infuriated. But the friar feared no man, giving himself entirely to preaching the Truth.

As the threat of invasion subsided, Savonarola’s influence waned and politics became increasingly turbulent. Elections occurred every few months, and power passed rapidly between his friends and enemies. All the while, his Florentine enemies plotted against him in secret, detesting his moral reforms, which made difficult the life to which they once were accustomed. When his authority to preach publicly was finally revoked and he was unable to defend himself, it was only a matter of time.

On Palm Sunday in 1498, Savonarola’s enemies went to work. They stirred up the mob and readied to besiege the convent of San Marco. In his last homily, he proclaimed, “Lord, I thank thee for desiring now to make me in Thy own image.” The convent was attacked and he was captured. There followed weeks of imprisonment, torture, and forged confessions. He was condemned to die on May 23, 1498.

Savonarola’s last act before his death was to bow his head in acceptance of the plenary indulgence granted to him by the pope. His last words were those of the creed. After he and his two closest companions were hanged and burned, his ashes were thrown in the river to prevent anyone from collecting his relics. Since then, history has long attempted to bury his legacy, just as his executioners did; he was long regarded as a backwards hack who scared Florence away from renaissance progress. But recent scholarship has brought him into the light. Two of his foremost biographers, Josef Schnitzer (Savonarola) and Roberto Ridolfi (The Life of Girolamo Savonarola), have even predicted his eventual canonization as a saint, although this has not yet come to be. He died a faithful son of the Church, giving his life for the Bride of Christ, and never giving up on the word of God, even when it cost him his life. Though his ashes were scattered, his legacy lived on.

Source: Ridolfi, Roberto. The Life of Girolamo Savonarola. Translated by Cecil Grayson. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1959.

✠

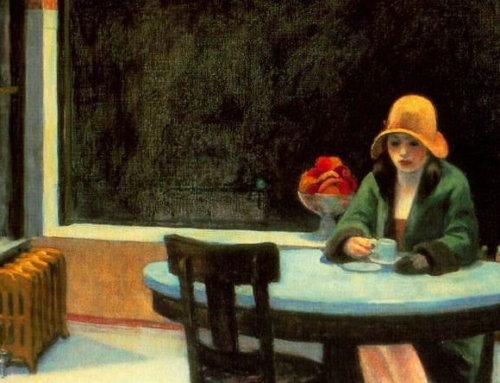

Image: Filippo Dolciati, Execution of Girolamo Savonarola