“Where is the good in goodbye?” sings the barbershop quartet standard, a song musical buffs will remember from The Music Man. This wordplay expresses a common experience: goodbyes are often sorrowful, if not downright heartbreaking. Just think of the curbside of airports and the lingering embrace of tearful lovers.

A poignant goodbye is captured in the 1964 French film, Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. A draft notice turns a young couple’s exuberant affection into tragic sorrow. As the train pulls them apart, their sorrow is heightened by both the intensity of their shared love and the length of their impending separation.

By this logic, the Ascension of Christ into heaven should have devastated the Apostles. Christ is infinitely loving and loveable, more so than any ordinary human being. Plus, Christ left without a return date. Two thousands year later, the Church still awaits her Bridegroom’s return in glory.

However, against this logic, the Apostles are anything but devastated. Just read the Gospel for the Ascension:

Then he led them out as far as Bethany,

raised his hands, and blessed them.

As he blessed them he parted from them

and was taken up to heaven.

They did him homage

and then returned to Jerusalem with great joy,

and they were continually in the temple praising God. (Lk 24:50ff.)

Instead of being heartbroken, they are filled “with great joy.” What’s going on here? Were the Apostles glad to be away from Jesus? Of course not. That’s absurd. So then, why the joy?

St. Thomas provides an answer in his discussion of the Ascension (Summa theologiae III, q. 57). He writes:

Although Christ’s bodily presence was withdrawn from the faithful by the Ascension, still the presence of His Godhead is ever with the faithful, as He Himself says: “Behold, I am with you all days even to the consummation of the world” (Mt 28:20).

In the beginning of Matthew’s Gospel, the angel tells Joseph that Mary’s child will be Emmanuel, meaning “God is with us” (Mt 1:23). At the end of the same Gospel, as St. Thomas cites, Jesus affirms that He is eternally Emmanuel. The Book of Revelation concludes with the affirmation that God will be with the faithful for all eternity (Rev 21:3).

The Ascension is not your usual goodbye. Christ ascends body and soul to God’s right hand. But in a spiritual manner, He still remains with His faithful. Such a goodbye recalls the very etymology of the word. “Goodbye” comes from the older expression, “God be with you.” Thus, when the God-Man says goodbye, He’s saying: “Though I depart in body, I still remain with you.”

Still, one might object: what good is such an invisible presence? Show me the presence! To this objection, we reply with the sacraments. For example, in confession, we hear the healing words of Christ’s forgiveness, and in the Eucharist, we taste and see the goodness of the Lord. Remember how, earlier in Luke’s Gospel, Christ disappeared at the breaking of the bread (Lk 24:30-31). His bodily presence gave way to His sacramental presence, both of which are Real Presences.

We also should turn to Mary, Christ’s mother and ours. After the Ascension, the Apostles gathered around the Blessed Virgin. She had borne Christ not only in her womb, but also in her heart. As our mother, she teaches us how to know and cherish His presence around us and within us. Gathered around her, we too can share the Apostles’ joy, the joy of the unfailing presence of Jesus.

✠

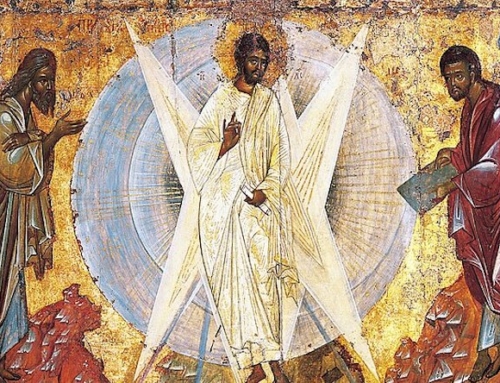

Image: Fr. Lawrence Lew O.P., The Lord Ascends into Heaven (used with permission)