He stood alone on the stones, his mess-tin spilled at his feet. Out of the vortex, rifling the air it came – bright, brass-shod, Pandoran; with all-filling screaming the howling crescendo’s up-piling snapt. The universal world, breath held, one half-second, a bludgeoned stillness. Then the pent violence released a consummation of all burstings-out; all sudden up-rendings and rivings-through – all taking-out of vents – all barrier-breaking – all unmaking. Pernitric begetting – the dissolving and splitting of solid things.

In his high-modernist World War I epic, In Parenthesis, the poet David Jones transfigures German artillery fire into an apocalyptic event of cosmic proportions. The brass-shod shell becomes the herald of reality shattered, a sign of the unraveling of the very identity of the world.

Though our experience is by no means so dramatic, we who have grown up in a post-war(s), secular West have in many ways inherited this fragmented reality and unraveled identity. Cultural crashes like divorce, abortion, and the normalization of homosexual behavior point to a profound rupture in the fabric of our society – one that public scandals, urban violence, and the shallow theatrics of the entertainment industry do nothing to mend. Even the more innocuous shift towards digital social relationships points to a parallel problem at the personal level: the anonymity of the Internet is replacing the familiarity of the neighborhood. There is a profound ambiguity about who we are as modern men.

But Jones’ prose-poem does not end with this cataclysm. If it was merely a tale of cultural existential crisis, W. H. Auden would likely not have called it “very probably the finest long poem written in English in this century,” nor would T. S. Eliot have called it “a work of genius” if it merely deconstructed our social identity. Jones’ epic is so good because, while it powerfully depicts the horrors of being an infantryman in the Great War (Jones himself was wounded at the Battle of Mametz Wood), it does not give horror – or nihilism – the last word.

With high-modernist skill and religious intuition, Jones breathes meaning into atrocity by seeing a profound connection between contemporary events and the whole of his tradition (which means: Western, Celtic, and Catholic). Jones does not “justify” the horrors of war – he does not try to find a meaning for violence qua violence – but rather he finds meaning by situating it within a much larger whole.

Consider the almost surrealist monologue that Private John Ball (the main character) witnesses in Part 4 of the book. After surveying a number of men whose fitness for battle is questionable, an old soldier named Dai Greatcoat – who seems to be every soldier of every time – offers this “boast”:

I was the spear in Balin’s hand

that made waste King Pellam’s land . . .

With my long pilum

I beat the crow

from that heavy bough . . .

I heard there, sighing for the Feet so shod.

I saw cock-robin gain

his rosy breast.

I heard Him cry:

Apples ben ripe in my gardayne

I saw Him die.

I was in Michael’s trench when bright Lucifer bulged his primal salient out.

That caused it,

that upset the joy-cart,

and three parts waste.

You ought to ask: Why,

what is this,

what’s the meaning of this.

Because you don’t ask,

although the spear shaft

drips,

there’s neither steading – not a roof-tree.

This is but one of many passages where the mythic, the biblical, and the current blend together such that they cannot be separated. What we are left with is a seamless whole, a garment that cannot be torn. The consequence is that a broader context and richer identity transforms the moment. To ask “why” about the horrors of WWI was also to ask “why” about the death of Christ on the cross, “why” about the fall of Lucifer, and “why” about the dealing of the blow that led to the grail quest and the collapse of Arthur’s Britain. For the poet, as for God, things can signify things, and events can signify events. It’s not the violence that has meaning, but the whole, of which the violence is but one part.

And here’s the most important thing: Jones is able to see the whole in each of the parts – the knight Balin, the centurion Longinus, and Michael’s angelic host are all present in Dai Greatcoat. He can see this precisely because he is aware of his own tradition. He recognizes a connection between himself and everything that has come before him. He knows that Divine Wisdom has ordered all things with a single purpose, and it is of that purpose that he calls us to inquire: “why, what is this, what’s the meaning of this?”

But can we – as a society – learn this lesson? Can we even ask this question, or are we too disconnected, too fragmented for it to bear any meaning? Jaded cynicism and ironic skepticism have undermined our ability to see the world with eyes of faith. Individualism has shifted the focus away from the whole and onto the part. And technology is increasingly drawing us out of the real and into the virtual. If all this is true, it seems impossible to expect contemporary, secular man to interpret his real sufferings in light of the connected whole of a tradition enlivened by faith. But if he can’t do this, how will he make sense of the evils in our world? One answer is avoidance – there’s always another movie to watch – but is that enough?

Here’s a final passage from In Parenthesis. Private Ball is describing the exit of his unit from camp on a rainy afternoon:

Corporal Quilter intones:

Dress to the right – no – other right.

Keep those slopes.

Keep those sections of four.

Pick those knees up.

Throw those chests out.

Hold those heads up.

Stop that talking.

Keep those chins in.

Left, left, lef’ – lef’ righ’ lef’ – you Private Ball it’s you I’v got me glad-eye on.

So they came outside the camp. The liturgy of a regiment departing has been sung. Empty wet parade ground. A camp-warden, some unfit men and other details loiter, dribble away, shuffle off like men whose ship has sailed.

Eyes of faith allow us to see even the most mundane aspects of our lives as a liturgy, with all the power of history and tradition behind it. Without this, the world reverts to being sombre and lifeless – “empty wet parade ground.” Jones is rooted in the former, and so is able to end In Parenthesis with the figure of the Queen of the Wood, who is also Mary, bringing serenity, solace, and honors to soldiers who have just been massacred.

In a few days we will celebrate what C.S. Lewis called the “true myth”: the Incarnation of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. Patriarchs foreshadowed Him. Prophets foretold Him. Even pagan legends paved the way for accepting Him. In the fullness of time, this tradition has been brought to completion, and we find our true identity when God and man meet in a manger.

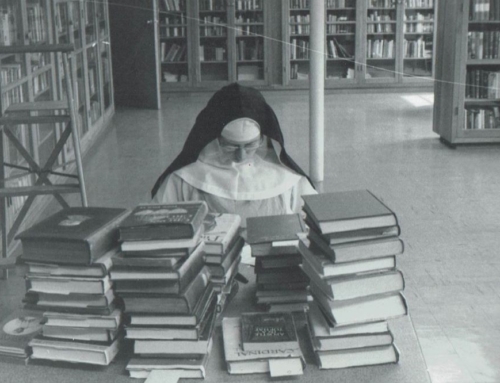

Image: Christopher Williams, The Welsh at Mametz Wood