As the Church celebrates this year honoring Saint Joseph, she also honors this saint as the patron of a happy death (CCC 1014). Why give this patronage to Saint Joseph? Tradition suggests that he died happily because he died in the loving company of Jesus and Mary. By dying as a friend of God, he gave us an example of the happy death.

Today, there is a new need to examine what a happy death is and what our spiritual care for the dying should look like. This need confronts us as individuals, as a political society, and as members of the Church. The pandemic has made this concern more public and perhaps more urgent, highlighting how much our culture could learn from the wisdom of a fifteenth-century pastoral handbook known as The Art of Dying.

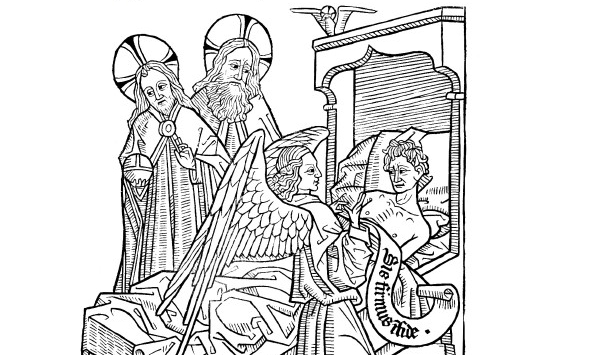

For this reason, the National Catholic Bioethics Center has recently published Brother Columba Thomas, OP‘s complete translation of this late medieval text. Its anonymous author, living and writing in the wake of the Black Death, offers wise guidance for the dying Catholic. Priests were lacking and catechesis was poor, but literacy was increasing, and thus the author hoped that a book could take advantage of increased literacy rates in order to aid the dying and their loved ones. For even greater accessibility, pictures for the illiterate supplemented the written word.

Although we now live in a very literate society, we find it perhaps more difficult than ever before to prepare for death today. To show how The Art of Dying could help us now, Thomas identifies three of its principles that should better inform contemporary Catholic bioethics and pastoral practice: First, the soul holds definitive priority over the body; second, the sacraments have a central role in Christian death; and third, spiritual warfare is real. A 2019 Dominicana post, anticipating this new publication, contains Thomas’s previous reflections on these topics.

As a further aid, Thomas’s new translation includes not only the late medieval text, but also related prayers and commendations. His research traces The Art of Dying‘s historical context and development, and he includes the fifteenth-century woodblock images, which Thomas faithfully paired with their appropriate sections as they were in the original. But what are we to make of the work itself?

The Art of Dying‘s first concern is the salvation of souls. It describes the angels and demons battling over a man’s soul at the end of his life. Devils tempt the dying man to commit sins of unbelief, despair, impatience, pride, or greed. In response, a good angel administers divine truth and dispels the demons’ lies through Sacred Scripture, sound theology, and hopeful encouragement. The angel guides the man through suffering and temptation to a holy death.

Even though this 2021 translation is of a fifteenth century work, the new edition shares the same pastoral concern as the original. Caring for the lay faithful at the hour of death is as important now as it was then, and The Art of Dying teaches unchanging truths about these last moments. Thomas’s annotations help show this by explaining not only historical matters but also points of sacramental theology and pastoral praxis. By doing this, Thomas’s notes make this work useful in our modern day.

In keeping with the medieval author’s intention, this book is of special interest to the laity, although priests, deacons, and seminarians would also benefit from it. Catholic medical professionals, those who care for the elderly, and certainly anyone working in hospice or palliative care would be well served by pondering the teachings of The Art of Dying.

We all hope to die in Christ, so as to rise on the last day. Thus, praying through and meditating on the mystery of Christian death, and the happiness of a Christian death, will help us one day to die like Saint Joseph. The Art of Dying re-opens a deep well of a spirituality of hope—hope that we too may hear the call of the Lord Jesus: “Come, O blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world” (Matt 25:34).

✠

Image from The Art of Dying (35) (used with permission).