Much has been written about the growth of secularism in the modern world, the future of religion in public life, and the appropriate Christian response. I would like to offer another perspective, trying to deal not so much with the details of the contemporary situation but of our disposition towards them. If Jesus Christ is the Lord of history, why does his Church appear to be in such a bind? To answer this question, I would like to take a walk through The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterton. What follows will contain spoilers, but I hope it might provoke a few to read a better man in his own words.

The protagonist of the book, Gabriel Syme, is an undercover police detective tasked with rooting out a group of anarchists from the streets of London. He is to make war against the philosophical nihilism and anarchism that have become fashionable in certain circles of society. As Gabriel works his way deeper into the organization of these anarchists, he encounters the very normal terror of isolation and of being found out. Being undercover in all these adventures, he, the detective, never has the power of law or the trappings of social respectability. He is alone. Moreover, not all these men are simple anarchists, that is, men who have felt some injustice in the world and seek to right it by violent means.

At the apex of the story, Gabriel, with his cover blown, is confronted with a “real anarchist.” This is a man who despises the police, not for any particular abuse of power, but for the fact of their power:

The only crime of the Government is that it governs … I curse you for being safe! You sit in your chairs of stone, and have never come down from them … you have had no troubles. Oh, I could forgive you everything … if I could feel for once that you had suffered for one hour.

This kind of anarchist hates order itself. The police have it too easy, the anarchist says: they are fat and happy and have never felt the pinch of danger or the daring of solitude. They have never taken a risk or felt the whole world against them.

Gabriel will have none of it. He responds to this non serviam, claiming that he, like everyone else in the universe doing good, has been seemingly alone, outmanned, and outgunned. Why has he been put in this situation?

So that each man fighting for order may be as brave and good a man as the [anarchist], so that by tears and torture we may earn the right to say to this man, “You lie!” No agonies can be too great to buy the right to say to this accuser, “We also have suffered….We have descended into hell.”

This is a trope common in most fiction, for an all-powerful hero makes a poor protagonist. The main character, or characters, must never have the comfort of official approval or help, at least not openly or completely. They lack the power of the law and must not count on the cavalry coming until the very last minute. In the plan of providence, the “good guys” must always be working under poor conditions, their backs to the wall, a single step from failure. This disposition of desperate courage and daring seems sensible in our current situation. To be good is not the same as to be tame, to love order is not the same as to love monotony, to seek for peace is not a plea for conformity. Like Christ, our hope is in the loving plan of the Father, who will work out all things in the end. God, in his goodness, has a flare for the dramatic, and his stories do not end with a whimper, but in a bang. Understood this way, The Man Who Was Thursday turns into an accounting for the seeming inefficiency of providence, hinting that God also has skin in the game.

✠

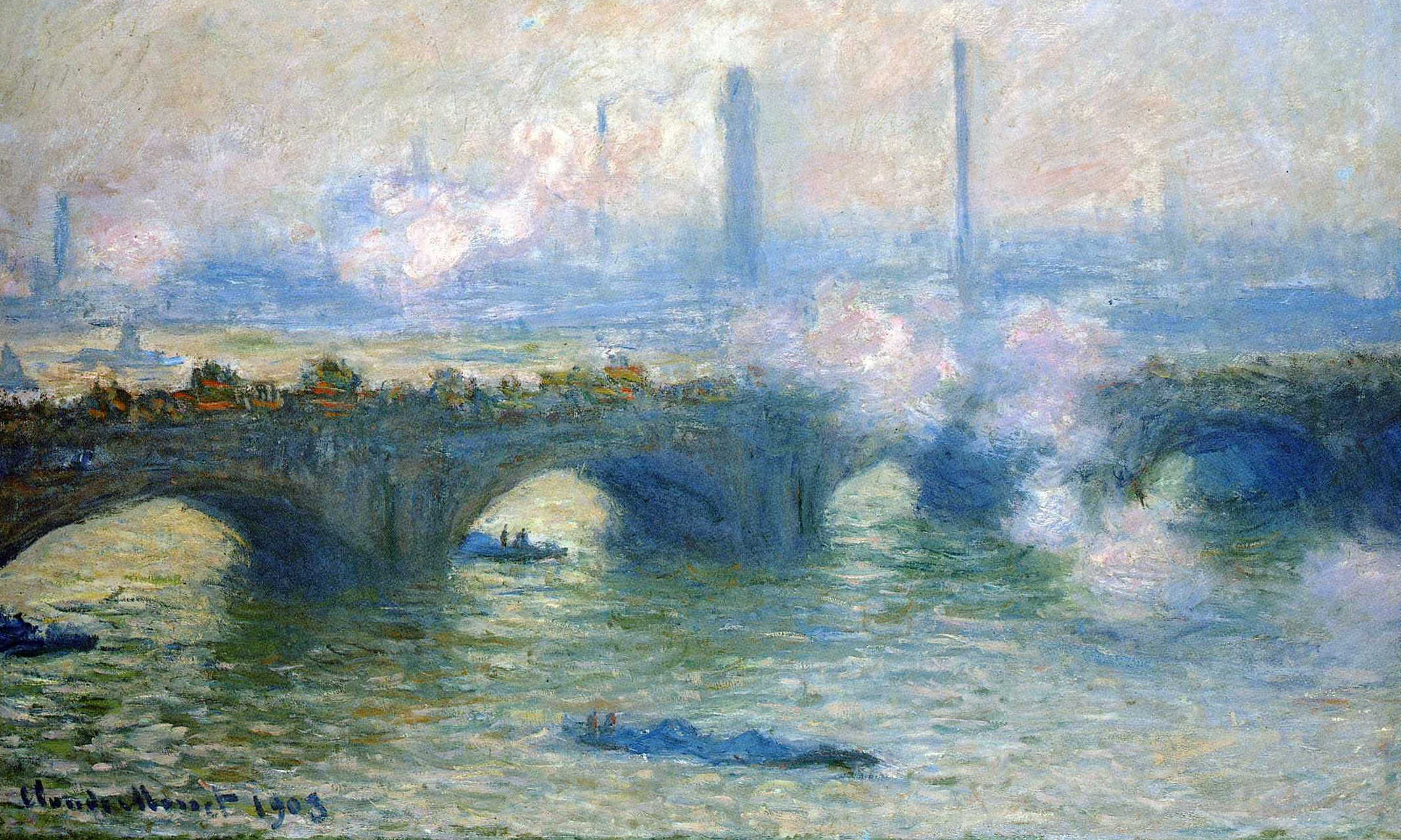

Image: Claude Monet, Waterloo Bridge, London