The only difference between heaven and hell is the way you think about yourself.

At least to some people today, this is the real distinction between salvation and damnation. There is a great divorce between heaven and hell, but the chasm between them is only one of positive and negative feeling. While the above reasoning certainly isn’t true, it does at least raise an important question. We don’t stop thinking once we die, so then what is on our minds in these eternal realities?

To answer to this question, we need to look at some concrete human emotion, like pity. When we think of the word pity, we think of a feeling of sorrow we have in response to another’s suffering. It is the gut reaction we have to seeing another person in pain, and we feel awful for the sake of their suffering. From this pity can come the further response of compassion, where we intend to bring about good for the person in need of help.

But pity can also be used in the wrong way. Instead of comforting a person’s legitimate distress, pity can be used as a kind of sugarcoating that covers over the truth of the situation. C.S. Lewis says this kind of pity makes us concede what we should not concede, and flatter someone when we should have spoken the truth. Instead of bringing a person’s pain into the light by acknowledging their trouble, we hide it from them. In the hope of making them feel better, we distort the truth. We tell them that their faults aren’t so bad, that they have been wronged, and that a fairer world would have given them better.

This false pity becomes even worse when we apply it to the way we think about ourselves. Self-directed pity tends to bend and twist the truth in our favor. It creates, fabricates, or at least exaggerates, a grievance done to us, and draws others into feeling sorry for what we have really done to ourselves. Self-pity is what makes a child lock himself in the closet because he wants his parents to worry about him; and it is self-pity that makes us incapable of seeing a situation in a different light, and so admit we were ever wrong. It is also self-pity that keeps those in hell closed in on themselves, not wishing to see a light of truth beyond their individual and colored sentiment. Instead they brood on their vices and sins, telling themselves that their faults aren’t so bad, they were wronged, and a fairer world would have given them better.

If hell is full self-pity, then heaven has its opposite. Those in hell may be tightly bound around personal gripes and vices, but heaven has those who have neither hidden thought nor personal viewpoint. It is not as if those in heaven have forgotten about who they were, it’s just that they have lost self-interest. In contradiction to the self-pity of the damned, those in heaven have a perfect self-knowledge whereby they understand themselves completely. They recognize their finitude, and realize that their thoughts, being, and existence do not come solely from their own minds. They have seen themselves for who they really are, and, as a result, have asked for mercy. They have humbled themselves and have now been exalted.

If knowledge is the foundation of love, then the more something is known, the more easily it can be loved. Those in hell have shrunken reality down to their opinions, and, as a result, are no longer capable of loving something beyond that feeble form of ignorance. But the saints in heaven have moved from a knowledge of the imperfect to what is perfect. They have seen God, and have come to know themselves as the image and likeness of Perfection itself. Although none of us here on earth have moved to that state of glory, we can hope for heaven, and say with St. Paul:

For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood. (1 Cor 13:12)

✠

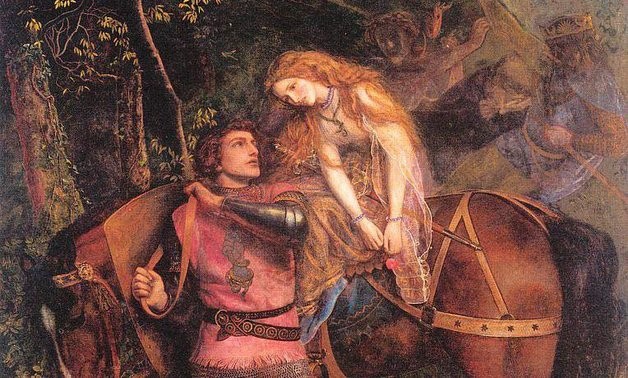

Image: Arthur Hughes, The Beautiful Lady Without Pity