This is part of a series entitled, “Preaching: Feeding Fellow Beggars.” Read the series introduction here. To see other posts in the series, click here.

One day in elementary school, my teacher was very angry with us for not understanding something she had already taught. She attempted to explain it again but was so furious that she screamed the lesson at us. I can’t even remember what the lesson was about. I only remember that my teacher was angry. I wonder if I ever really learned what she was trying to teach.

Preachers are not much different from teachers in this regard. While some preach with fire and brimstone, preaching with unfettered anger is often ineffective. And yet, Saint Paul tells us, “Make known with boldness the mystery of the gospel”

(Eph 6:19). What is the difference, then, between being a bold preacher and being an angry preacher? We find an answer in the example of the fourth-century preacher Saint John Chrysostom.

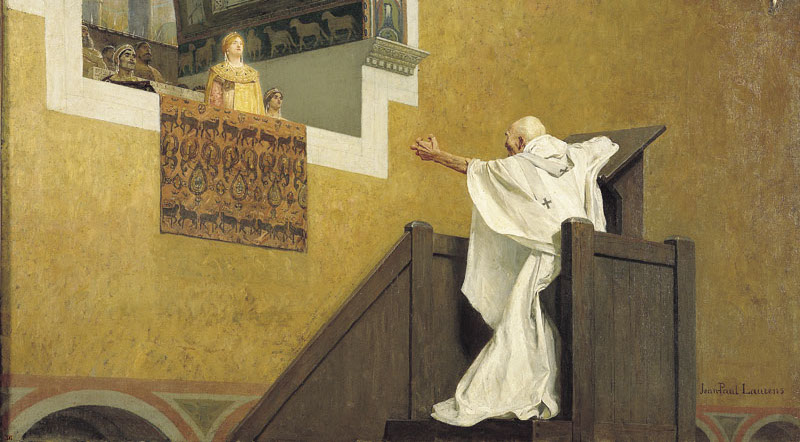

Early in his ministry in Antioch, John Chrysostom attracted large crowds with his powerful preaching. He was so effective that he was later taken by military force to Constantinople and consecrated as archbishop. It seemed fitting that one of the finest orators should minister in one of the largest churches of the empire. But while he won the hearts of many of the faithful, he did not earn such favor from the political and ecclesiastical leaders in Constantinople. When the austere monk-turned-bishop saw the decadence of Constantinople, he wanted to clean house. Someone once compared his arrival in the city to an Amish farmer entering a nightclub. The sting of his preaching peaked when he publicly rebuked the empress Eudoxia, even comparing her to Herodias. He was exiled shortly after this incident and remained in exile until his death.

The boldness of John Chrysostom’s preaching is unquestionable. This boldness, however, may seem precariously close to anger. After all, the repulsive reaction of Constantinople’s leaders may lead us to wonder if his preaching was truly effective. But John Chrysostom knew the difference between preaching with boldness and preaching with anger, and that only the former was effective. When speaking about the discourse of the martyr Saint Stephen (see Acts 7), he teaches us about this distinction:

If we [speak] with wrath, it no longer seems to be the boldness [of one who is confident of his cause,] but passion. But if with gentleness, this is boldness indeed. . . . The boldness is a success; the anger is a failure. Therefore, if we are to have boldness, we must be clean from wrath so that none may attribute our words to wrath. No matter how just your words may be, when you speak with anger, you ruin all—no matter how boldly you speak, how fairly you reprove, or whatnot. (Homily 17 on Acts 7.35)

John Chrysostom touches upon a key point: the passion of anger can make our words ineffective, while boldness governed by reason helps them sink in. Saint Thomas Aquinas teaches that anger is a passion that can sometimes be contrary to reason and thus sinful (ST Ia-IIae qq. 46, 47, and 48). But that is not always the case. The heat of our passions can still be governed by reason. Aquinas understands anger as an aversion to any injustice. This aversion does not necessarily entail being dominated by emotion. It entails hating whatever disrespect or mockery replaces the good that someone deserves. And when God is treated unjustly through mockery and disrespect of his precepts, this is most especially the appropriate occasion to be angry. A just rebuke and correction, therefore, is to be given.

Boldness in preaching may come across as anger. But beneath the passion is an attempt to address the injustices rendered to God. The decadence of elites and their disrespect for the poor in Constantinople deserved bold correction because God deserves all honor. Righteous anger out of love for the Lord and his poor gets to the heart of John Chrysostom’s boldness. The true source of his fiery preaching was the one of whom he spoke: God. His preaching was both bold and effective because he knew that if his preaching was going to be any good, it must be about God.

When John Chrysostom was dying in exile, he received the Eucharist and reportedly offered his last prayer with these words: “Glory to God for all things.” These final words of one of the finest preachers capture his entire ministry and what makes anyone a fine preacher. Unbridled anger breeds resentment, but that’s not what we see in Chrysostom’s preaching. Instead, he ends his life with words of praise. What inspired John Chrysostom’s preaching wasn’t simply passion but fervent hope in God and his promise of salvation (cf. 1 Thess 5:9). “Without understanding that fervor, we will not make sense of his homilies, his prayers, or his life” (Andrew Hofer, The Power of Patristic Preaching, 169). For John Chrysostom, God’s glory and honor were worth protecting with boldness, even at the cost of seeming angry. But he still knew how to avoid the sin of anger, because he knew that anger devoid of reason is devoid of God. And he always had a reason to speak boldly: salvation was on the line.

One hundred and fifty years after his death, Saint John was given the title “Chrysostom,” which means “golden mouth.” Despite the bitterness people felt at hearing his words, they later realized their worth in gold. Saint John Chrysostom wanted his preaching to lead people to the message rather than the preacher. Unjust anger—when passion is divorced from reason, and perhaps from the truth—tends to draw people’s attention to the preacher. But boldness—being unafraid to present what others need to hear—can lead them to the message: to the God that will save them.

✠

Image: Jean-Paul Laurens, Saint Jean Chrysostome et l’Impératrice Eudoxie (public domain)