It is a fact widely acknowledged that man’s common intellectual heritage suffers from a dearth of theological analyses of Sherlock Holmes. Emboldened by the direness of the need, I will overlook the inadequacies of my own pen and turn now to make some small redress of this lamentable paucity.

Sherlock Holmes is, like any artist, a keen observer of the material world, and he uses his art to reconstruct and anticipate malefactors’ movements by analyzing the physical traces left by their patterns of behavior. Some mistake his art for mechanism, considering Holmes to be a prophetic voice for twenty-first century scientific determinism, able to solve crimes because he knows that the world of men is reducible to mere matter and the physical laws that govern it; the delightful pair of Robert Downey, Jr., Sherlock Holmes movies take this idea to its entertaining extreme. But in Doyle’s vision, his master detective is no materialist; he is merely a man who understands the meaning of the body.

The body confounds modern men. We consider it to be an instrument of power, of domination, of pleasure, a tool to be employed and sometimes surgically altered to fit the needs of one’s true self. But Bl. John Paul II—and Sherlock Holmes—understand the body differently.

In his sprawling theological masterpiece, A Theology of the Body, Bl. John Paul says that before the fall of Adam and Eve the human body was a perfect means of communication, enabling the first man and woman to see and understand each other at the deepest level of their personhood. By its original design, the body “expresses the person in his or her ontological and essential concreteness, which is something more than ‘individual,’ and thus expresses the human, personal ‘I,’ which grounds its ‘exterior’ perception from within.” But the first sin ruptured the body’s perfect ordering to the soul, darkening that once-clear mirror with the stains of incomprehension, weakness, malice, and concupiscence. The body still communicates the soul, but it sends confused signals, obscuring as much as it reveals. Man has become a mystery to himself.

The brief Holmes mystery, “The Adventure of the Empty House,” exemplifies man’s struggle in a world of confused and confusing bodily signals. In the story, Holmes sets out to catch his sworn enemy, Colonel Sebastian Moran, a once-noble veteran of the British service in India, whose former reputation for courage and self-sacrifice hides his current life of murderous depravity. Knowing Moran intends to kill him, Holmes sets a wax bust of himself behind the drawn shades of his study to fool the murderer into thinking Holmes is an easy victim, sitting all unsuspecting and alone. He then lies in wait with Watson in the eponymous empty house across from his Baker Street home. Moran enters the same house and, using a nineteenth-century sniper rifle, shoots the bust, thinking he has killed his great nemesis. At that moment, Holmes springs his trap, arrests the would-be killer, and life goes merrily on.

While Moran is being arrested, Watson remarks with shock that “with the brow of a philosopher above and the jaw of a sensualist below the man must have started with great capacities for good or for evil.” But the chaotic and unpredictable course of Moran’s life gives the lie to the reductionistic physical analysis Watson attempts; a man’s mien is not his measure. We may desire to imagine all evildoers as crabbed, frightening men with baleful gazes, but life is not so simple. During a summer I spent ministering to men on death row in a super-max prison, I was often struck at how ordinary and unremarkable the men appeared, knowing full well that they had committed crimes that beggar description.

The body considered as a static thing cannot reveal the true character of a human being, despite the claims of nineteenth-century phrenologists and contemporary genetic determinists. The human person reveals himself through his actions, through the tangled web of careless, generous, hateful, and loving deeds that constitute his life. Holmes’ great art is to learn what is in a man’s heart by observing his mode of being; to do this, he must look beyond his own desires and see the other as he really is. Watson, like the rest of us bumbling knaves, cannot see the personhood of the man before him because he is confused by his erroneous presuppositions about how to decode the body’s mixed signals. Only Holmes, by long discipline and rigorous honesty, has trained himself to read the garbled messages of a human life and see the real person they communicate.

The story ends with an iconic tableau of Holmes standing before the bullet-blasted bust of himself. The scene discloses the two fundamental modes of approaching the body. The frozen, static wax bust is a body of seeming, a construct of the viewer’s presuppositions and the sculptor’s desire to hide his true self. The living, dynamic man who confronts it is the Holmes of being, who slowly reveals glimpses of his true personhood to those who care to follow him through the twisting career of his life. The casual or malicious observer cannot access this inner man. Only those who love the truth can follow it as it points toward the final mystery of the human person.

✠

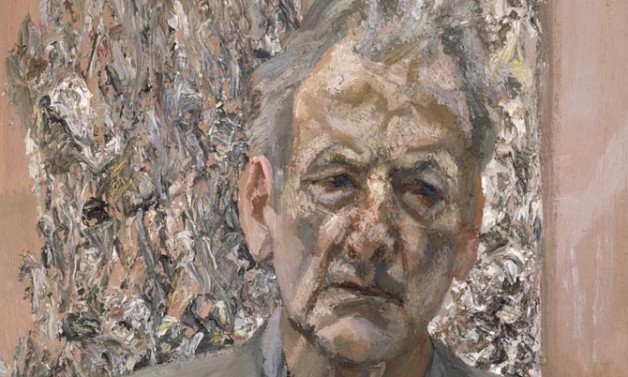

Image: Lucian Freud, Self-Portrait: Reflection