Over the weekend, we passed through the vernal equinox, which means that (at least here in the Northern Hemisphere) the days are now longer than the nights. With the increase in daylight comes higher temperatures, the melting of the snows that battered our landscape this winter, and the return of the flora and fauna that show nature at its liveliest.

Every culture has some ritual to mark this arrival of spring and the rebirth of nature, from the fertility rites of the ancient Romans and Egyptians to the opening of baseball season in our time. My own ancestors in Poland had the custom of constructing an effigy of the Winter Maiden out of straw, then ritually drowning her in the nearest river. Any festival or rite to commemorate the coming of the spring season involves giving thanks in some way for the gifts of nature. But when such an offering is being made to nature, the results can be brutal.

Perhaps the best example of this brutality is the vernal pagan liturgy from my brother Slavs, the Russians, depicted in Igor Stravinsky and Vaslav Nijinsky’s ballet, The Rite of Spring. The ballet’s odd dance rhythms and dissonant chords generated tension, right from the opening bassoon solo playing as high as it possibly can, which led to a riot at the show’s premiere in Paris over a century ago. Its initial notoriety, however, has turned into acclaim, as the ballet has since been recognized as a groundbreaking work. A generation later, some of the music would serve as the soundtrack for an animated segment illustrating the evolution of life, from the early earth to the extinction of the dinosaurs, in Walt Disney’s Fantasia—thus giving the work a further connection with the rhythms of nature. (As a boy, the scene in which a Tyrannosaurus Rex fights a Stegosaurus to the strains of “The Glorification of the Chosen One” was my favorite part of the movie.)

The first act of the ballet, “The Kiss of the Earth,” shows what many in today’s postmodern culture find attractive in paganism: an opportunity to reconnect with nature. After a fortune-teller reads the signs of nature and determines that spring has, in fact, returned, the people of the village perform several group dances and ritual games, until the tribe’s elder, the Sage, arrives and blesses the earth—leading the people to dance frantically until they drop.

But the second act, “The Exalted Sacrifice,” shows that paganism is not all fun and games. At night, a group of thirteen adolescent girls dances in a circle, until one of them trips, signaling that she is “The Chosen One.” The other maidens call upon their ancestors, and then the Chosen One performs an elaborate and vigorous dance, becoming the victim of the annual sacrifice by literally dancing herself to death. The ballet ends with the shocking image of this maiden’s demise, meant to appease the pagan earth deities.

What a nasty and cruel end for those who want to get back in touch with nature! Yet, The Rite of Spring does indicate something true: we owe a great debt—not to the gods but to God—for the wondrous gifts of creation, not only the marvels of springtime, but our very lives as well. Now if only there were a way to make satisfaction to God without a yearly human sacrifice…

In the Old Testament, the people of Israel did have a system of sacrifices that only required animals as victims—an improvement, to be sure. Several sin-offerings aimed to make propitiation to God for the nation’s misdeeds, and the springtime sacrifice of the Paschal Lamb thanked God for the particular gift of constituting the Israelites as a chosen nation and freeing them from the bondage of Egypt. Yet even these sacrifices did not suffice to liberate the people from their greater slavery to sin, or satisfy for our infinite debt to our Creator.

Only Jesus Christ, both fully human and fully divine, could make such satisfaction. As we read in the Letter to the Hebrews,

For if the blood of goats and bulls and the sprinkling of a heifer’s ashes can sanctify those who are defiled so that their flesh is cleansed, how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal spirit offered himself unblemished to God, cleanse our consciences from dead works to worship the living God. (9:13-14)

While the virtuous sacrifices of the Old Testament prefigured the Cross of Christ, and the vicious, ‘deadly works’ of human sacrifice among the pagans at least pointed to the existential need for a Redeemer, Jesus’ self-offering, once and for all, restored our fallen human race to friendship with God.

Moreover, Jesus chose to make his offering for our redemption during the springtime Paschal sacrifice, because “‘it is then that day grows upon night; because by our Savior’s Passion we are brought from darkness to light’” (see St. Thomas Aquinas, ST III.46.9 ad 3). The Incarnation, in which God the Son took on our human nature and entered His creation, was the true “Kiss of the Earth,” and so His redemptive death on the Cross, the true “Exalted Sacrifice,” is the subject of the Church’s own rites of spring. As we approach the high drama of the liturgical events of Holy Week, let us give thanks to God, not only for the gift of springtime, but for the even greater gift of our salvation.

✠

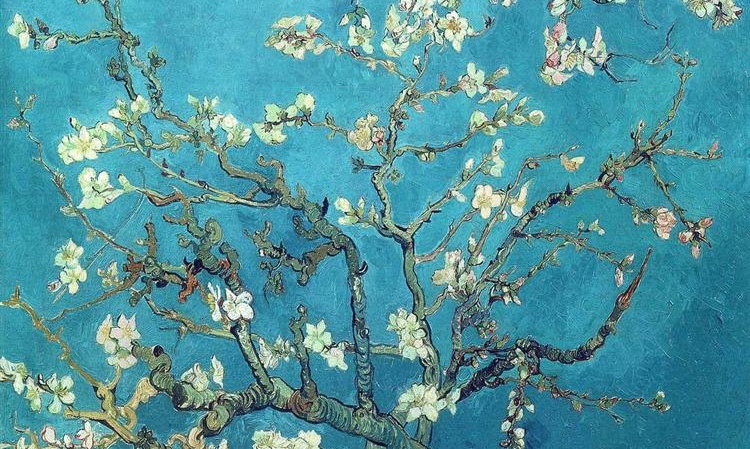

Image: Vincent van Gogh, Branches with Almond Blossom