Pope Francis announced that 2015 would be the Year of Consecrated Life. Consecrated men and women give themselves completely to Christ, renouncing definite goods of this world so as to be more perfectly united to Him and to serve as witnesses to His Kingdom. Lumen Gentium teaches,

The religious state, whose purpose is to free its members from earthly cares, more fully manifests to all believers the presence of heavenly goods already possessed here below. Furthermore, it not only witnesses to the fact of a new and eternal life acquired by the redemption of Christ, but it foretells the future resurrection and the glory of the heavenly kingdom. (44)

The purpose and importance of consecrated and religious life seem to be slipping from the world, even in the Church itself. A life given to contemplation and apostolic endeavors through the evangelical counsels of poverty, chastity, and obedience does not fit into the utilitarian framework cultivated by minds today. Nevertheless, Christ’s faithful must work to promote the gift of consecrated life for the sake of the Church and all peoples.

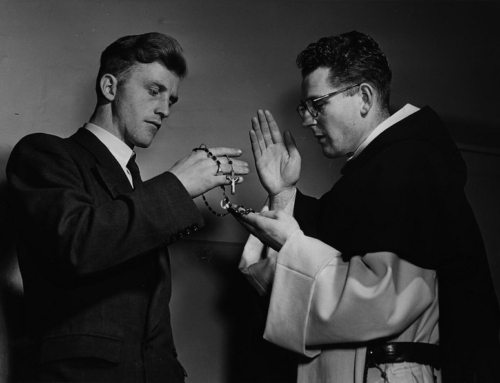

Archbishop Anthony Colin Fisher was appointed the archbishop of Sydney by Pope Francis in September 2014. Before his appointment to the See of Sydney, he was the auxiliary bishop of Sydney in 2003 to 2010 and was the bishop of Parramatta, Australia, from 2010 until 2014. Archbishop Fisher was born in 1960 in Sydney. He entered the Order of Preachers in 1985 and was ordained a priest in 1991.

He completed his doctoral studies in bioethics at the University of Oxford in 1995. He has lectured at the Australian Catholic University and at the University of Notre Dame (Australia). From 2000 to 2003 he served as the foundation director of the John Paul II Institute for Marriage and Family, in Melbourne. Archbishop Fisher served as the organizer of the 2008 World Youth Day in Sydney. Before his episcopal appointment he also served as Master of Students in the Dominican Province of the Assumption in Australia. Archbishop Fisher has written and lectured extensively on Catholic bioethics, abortion, in vitro fertilization, euthanasia, and healthcare. After his appointment, Jacob Bertrand Janczyk, O.P., conducted the following interview with Archbishop Fisher.

- In this issue of Dominicana the student friars are focusing on the importance and relevance of consecrated life in the Church and in the world at large. In Vita Consecrata, Pope Saint John Paul II writes, “Its universal presence and the evangelical nature of its witness are clear evidence—if any were needed—that the consecrated life is not something isolated and marginal, but a reality which affects the whole Church” (3). In what ways do you think consecrated life affects the whole Church?

Let me begin with a via negativa. In Australia, like many parts of the Western world, religious life has been in decline over the past few decades. Not uniformly, not always and everywhere: the orders with a strong sense of identity (often marked by a habit), community, prayer and a clear common apostolate still seem to attract some vocations. The Dominican and Capuchin Franciscan men, the consecrated members of some ecclesial movements, and some overseas congregations with a presence here (such as the Nashville Dominicans and the Alma Mercies) are getting vocations. But in general the picture for religious life down-under seems gloomy. I think the Church in Australia has hardly begun to realize what an impoverishment that is—to its prayer life, its apostolic energy, its creativity and its holiness.

When we realize what this decline or absence means, we will realize what a huge plus thriving religious life is for the Church. Where religious life flourishes the Church flourishes in her prayer and evangelical and eschatological witness; without it, the Church struggles. No doubt, this is part of why Pope Francis has decided that 2015 is to be dedicated to consecrated life.

- The idea of consecrated life in today’s increasingly secular culture seems in many ways to have lost the notion of the sacred, even amongst Catholics. Do you think that the “universal presence and evangelical nature” of consecrated life is clear evidence that it is neither isolated nor marginalized in the Church? In other words, is religious life compatible with the 21st century?

Though the forms vary over the centuries and no particular version of religious life is essential to the nature of the Church, nonetheless I think there is every reason to think that in every age there will be forms of religious consecration called forth by the Holy Spirit and appropriate to the times. Even apparently perennial forms—such as the monks and friars—have evolved over time. Often it has seemed that religious life is dying and that it is no longer relevant; what has followed, after an experience of desert, has often been a real flowering of religious life. Consider, for instance, the state of the Dominican Order (and of other congregations) in the Europe of the age of ‘Enlightenment’ and after the French Revolution and the Napoleonic campaigns: things seemed desperate. Who could have guessed that the second half of the nineteenth century would see the greatest flowering of new religious congregations in history, spreading across the globe (including far-flung Australia!) in works of missionary endeavor, of education, healthcare, welfare and the like? I expect something equally surprising in this new secular age: a new evangelization in which religious life once again plays a crucial role.

That religious life might seem ‘incompatible’ with modernity and its overemphasis on immanence at the expense of a sense of transcendence is itself a challenge and opportunity: challenge, because it means many young Catholics never even entertain a religious vocation and many of those who are already religious end up more children of the secular age than of the Gospel; opportunity, because so many people seem to be thirsting for something better and we can stand out as a radical alternative more clearly than at some other times in history. Whatever else we stand for, religious obviously do not (or should not!) stand for mass consumerism, sexual recreationalism, ‘the throwaway society’ in which no commitment or self-sacrifice is possible or desirable, the materialist age that only values those things that can be seen and exploited: we are different and, hopefully, obviously so.

That said, there are also many admirable things in modernity which we religious rightly find simpatico and with which we can work in common endeavors.

- The Church teaches that “the first and foremost duty of all religious is to be the contemplation of divine things and assiduous union with God in prayer” (Code of Canon Law 663.1). Could you elaborate on how this is reconcilable with the apostolic mission of consecrated men and women?

It’s an important question in a world that more than ever values people (and so we value ourselves) by what we do—what we make, what work targets we achieve (our KPIs [i.e., our key performance indicators]), what we come to possess. There always appears to be a good ‘apostolic’ reason to reduce our prayer time.

I recently read about Mohamed El-Erian, the former CEO of trillion-dollar investment fund PIMCO. After repeatedly refusing his entreaties that she brush her teeth, his ten-year-old daughter presented him with a list of twenty-two times he had not be there for her at important moments in her life: her first day at school, her first soccer match, her parent-teacher night, a parade and so on… Of course he had good work reasons for missing these things: travel, meetings, urgent phone calls. But his daughter’s list was a wake-up call. His work-life balance was askew and his job was overshadowing everything else in his life, including his relationship with his daughter. He was not giving her what she most needed and valued from him: his time. So earlier this year he quit his job and now works part-time so he can share the child-raising with his wife and be with his daughter more. There’s a lesson there not just for parents but for us religious.

Blessed Teresa of Calcutta was once asked by a young priest-bureaucrat how much time he should pray each day. She immediately recommended two hours a day. But, he responded, she surely did not know how much he had to do and how important his work was. His ecclesiastical tasks were so demanding, deadlines had to be met and so much depended on him. “Oh I’m sorry,” she said apologetically, “I hadn’t realized how important and demanding your work is: in that case you need to pray four hours a day!”

It is in fact the special charism of Dominicans to contemplate God and the things of God in order to pass on the fruits of this contemplation to our students, parishioners, etc. Balancing contemplation and action might be difficult, but it will be impossible to engage in fruitful action unless time is devoted to prayer and contemplation, and a contemplative spirit developed.

- In the years following the Second Vatican Council, the Church experienced many changes in consecrated life, particularly an enormous decrease in numbers. What do you think needs to change or to be done by the Church and/or her faithful to reinvigorate consecrated life throughout the world?

The numbers in vows of religion have varied over the centuries, and after the huge rise in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the numbers were probably bound to fall—a bit like bubbles in housing or stock prices. There’s no right number of religious: 10%, 1%, 0.1% of Catholics… But there is a wrong number: 0%. We should be more alarmed by the decline in religious, priestly, married and parenting vocations in the West than we are. I remember some years back an Australian Dominican who, when asked what he thought we should be doing that we were not presently doing, said “panicking.” Of course, panic never helps us make good judgments; I also happen to think that our current situation gives more causes for optimism than this friar’s clever answer suggested. Nonetheless, he was right to suggest that we should have been taking the state of religious life more seriously than we did—and do.

The biggest thing that needs to be done about all this is, I think, that religious themselves recover their original inspiration (as appropriately evolved) and apply themselves with radicalism to it: not half-heartedly, not comfortably, not in a compromise with the zeitgeist. It also demands that the rest of the Church much more self-consciously and publicly value who religious are and what they do for the Church. Next year’s Year of Consecrated Life presents a good opportunity for the Church in this regard.

- Pope Francis has called for Synods of Bishops on the Family to meet in 2014 and 2015. It is clear that the family and family virtues are in constant attack today. Could you speak about the interplay between the Gospel witness of consecrated life and the role of families?

Too often I think family life and religious life are seen as alternatives. Of course it’s true that you have to choose one or the other, as your life-plan, your vocation. But that doesn’t mean there are two different species: the natural spouse-parents and the natural celibates. We are all natural spouse-parents and we are all supernatural celibates. Many of the same qualities are needed for each: a willingness to commit, for the long haul; an ability to compromise our own willfulness, to undertake acts of self-sacrifice; an eye to a common good beyond our personal preferences and pleasures; a certain generosity of spirit; a willingness to live and let live with others, to forgive, to grow through hurts; constant recourse to prayer, to divine grace, to live a vocation that often grates against our natural selfishness and that is little supported in contemporary culture. My thought is that sacramental marriage and religious life have far more in common than either of these states has with contemporary single or married life in the secular culture. That means that the gifts and challenges of families and religious communities should speak to each other, should be examples, witnesses, supports to each other. Of course, as Mary Eberstadt has shown, healthy families lead to healthy religiosity in society—from healthy, Catholic families come healthy vocations to the religious life.

I suspect, too, that many of the pastoral problems that each of these states of life is currently facing have aspects in common, e.g., how to deal with individualism and with an unsupportive, even hostile, surrounding culture; how to correct for the limited Christian formation (and damaging malformation) people have received before they seek admission to these states of life; how to help people discern well a vocation and form people for it and support them in living it… So there may be a happy providence in the two family synods bookending the Year of Consecrated Life.

- You entered the Order of Preachers in 1985. What initially attracted you to religious life?

I read recently on a Dominican website that I entered the Order in 1965—i.e., when I was five years old! You are right that it was in fact in 1985. But I suppose vocations do start early. I had a great aunt who was a Mercy nun and I loved serving at the altar as a boy. So maybe there were some very early influences. From around the age of fifteen I thought seriously about priesthood and first considered the Diocesans (who were my parish priests) and the Jesuits (who were schooling me). I ultimately joined the Dominicans by a circuitous route. But my growing thought from at least age fifteen was that I needed the support of a community if I was to pray well and grow in virtue, and that I needed a clear apostolate with some intellectual grunt if I was to put all my gifts to God’s purposes. So when the Dominicans came my way they were the obvious choice. But even before then religious life had its appeal.

- What attracted you to Saint Dominic and the Order of Preachers in particular?

A friend of mine talked me into attending a national meeting of Catholic university student groups. I went along rather reluctantly, but there I met a fellow student who had been wanting to join the Dominicans since around the age of five! I already knew (and loved) some of the Dominican saints but I didn’t realize the friars still existed… We talked about why the Dominicans might be right for me and the more I found out about their particular mix of active and contemplative life, the community and study and liturgical elements of their life, and above all their preaching apostolate and determined orthodoxy, the more it attracted me.

When I got home pamphlets started arriving mysteriously in the post for me with titles like “So you’d like to be a Dominican…” The more I read—including Tugwell’s book, The Way of the Preacher—the more attracted I was. Eventually I met some real-life Dominicans and they failed to frighten me off. By then I was a lawyer. So I took leave from work and went backpacking around the world, to make up my mind. I eventually wrote to the Order in Australia from the opposite side of the world and got a reply, two months later in a different country, telling me to come home quick and join up. I have loved being a Dominican ever since.

- I have found time and again that I am surprised by different aspects of consecrated life. Certainly there is for all religious a period of institutional formation, but religious life is also a lifetime given over to the work of formation. What are some things that have surprised you about consecrated life?

As an amateur historian (history was my first university degree) I have been struck by the genius of religious life in its ability to come back after heavy pruning and to evolve new forms. So I think we can expect surprises…

As an amateur religious I’ve been surprised how hard it is to juggle all the aspects of religious life—there seem to be more good things to be and do than can fit into one life—and how often one brother is good at one aspect (e.g., community life), another at another (e.g., the academic or pastoral side), another at another (the contemplative or prayer dimension), and that together we seem to make one really good friar with several heads. When I started religious life I expected that all of us would be all those things—now I accept that we are doing well if we get most of it right and, between us in each community, get all of it. Occasionally, to my delight, I have indeed met men and women for whom religious life really has been a school of perfection in charity and who seem to have achieved all the aspects of their religious charism to a high degree—or at least God has achieved it in them.

- In 2003 you were appointed auxiliary bishop of Sydney by Pope Saint John Paul II. Now, in September 2014, Pope Francis has appointed you the archbishop of Sydney. How do you think your life as a consecrated religious, and a Dominican friar in particular, has prepared you for or currently influences your episcopal ministry?

Some religious and some diocesan clergy have suggested to me that on being raised to the episcopate I have effectively been released from religious life. My own view is that usque ad mortem [“until death,” the time period for which a Dominican professes solemn vows] means just that and that, as the canon law suggests, I should live as much of my religious charism as is compatible with my new office. In fact I’ve found the preaching part of my vocation magnified as bishop: I get more opportunities to preach, and different opportunities to teach, than I had as a priest friar.

I never get over the privilege that is preaching: I love it more than I did when first I started; and I think my Dominican life was the best of preparations for that.

The Dominican thing has obviously influenced the way I pray—I still love the Divine Office and miss singing it in common; and the way I study—I love collecting books and sometimes I even read them; and my football team of saints—St Thomas Aquinas is still my hero, with St Dominic and St Catherine great favorites also.

- How has being appointed to the episcopacy changed your life as a consecrated religious?

There’s obviously less community, a different kind of obedience and new challenges to live evangelical poverty while having oversight of significant funds. I have less support in my religious identity: I wear my habit as much as ever, for example, but I don’t have others around me doing so. Those who know me say I’m still very Dominican…

One quirky difference: I’ve developed a devotion to the Dominican bishop saints: Albert the Great, Antoninus Pierozzi, Pius V, Pedro Sanz Jordi, Francis Serrano Frias, Ignatius Delgado Cebrian, Vincent Yen, Dominic Henares, Jerome Hermosilla Liem, Josémaria Diaz Sanjurjo, Melchior García Sampedro and Valentine Berrio Ochoa. Then there’s the Dominican bishop blesseds: Guala of Bergamo, Bartholomew of Braganza, Innocent V, Benedict XI, James of Voragine, Augustine Kažotic, James Benefatti, Andrew Franchi, John Dominici, Terence Albert O’Brien, Benedict XIII and the soon-to-be-Blessed Pio Alberto Del Corona—there may be more! I regularly entreat their help…

- It seems that often what holds back young people from entering the consecrated life is the fear of commitment. Sometimes the idea of discernment becomes the limiting factor. What advice do you have for young people who may be considering a vocation to consecrated or religious life?

Four bits of advice. First, don’t romanticize discernment—as if there is one perfect vocation for you and by some magic process you can hit upon it and then must just do it. That’s no more realistic than thinking there is just one Mr Right or Miss Right out there for people and by magic or good luck they just have to find him or her and tie the knot or be doomed. Discernment means applying our minds and hearts to an important decision, and therefore thinking through all the pros and cons, taking counsel from wise others, praying and taking this to the Lord in the sacred liturgy. Ultimately you decide to give it a try and you (and your community) work out over time whether it’s right for you. Above all you hand it all over to God: I think we need a healthy theology of divine providence into which to situate our personal vocation, rather than a theology of me into which to situate God’s plans.

Secondly, don’t enter the Order of Perpetual Discerners. I know too many people my own age who are still deciding what to do with their lives, who or what to commit to, etc. Life has passed them by. Better to give something really good a go and see. If you intellectualize it and agonize over it indefinitely you’ll just end up with a big headache. You’ll never find the perfect fit, in religious life or married life: the fact is, we are fallen creatures and the best we can hope for is a fairly good fit.

Thirdly, ask your wisest friends, wisest family members, and some priest or religious for advice on what would fit your personality, gifts, virtues, and [what would] give you the opportunity to be the best you. Take that seriously and then, after all the rest I’ve suggested, decide. Deciding includes deciding not to keep weighing up and agonizing. It means taking the plunge.

Fourthly, let me say that the Church needs religious and many of your readers need religious life. There aren’t internet dating agencies to match them up. But if people do give it a go they just might find, as I have, that there is no more fulfilling life than this!

- Finally, what are your hopes for the state of consecrated and religious life in the Church for the future?

I pray daily for a spring-time for religious life in our Church. The new ecclesial movements give us reason to think there are new evangelical energies, new forms of Christian life, happening around us. I hope for a bright future for religious life. And I’m determined as a bishop to do my part in cultivating it on my diocesan and national patch. With Cardinal Pell I managed to lure the Nashville Dominicans and Alma Mercies out to Aus and now there are more than a dozen young Aussie girls in formation with them: that proves that there were women just waiting for something like that to join. There are many signs of hope.

To download a printable PDF of this Article from

Dominicana Journal, Winter 2014, Vol LVII, No. 2, CLICK HERE.