A Conversation with Calvinists

Editor’s Note: This is the third installment of a four-part reflection on the topic of predestination. The first two parts may be read here and here.

Halfway through our conversation, Michael, Gabriel, and I finally turned to one of the elephants in the room: reprobation. If predestination in general is the black sheep among Christian doctrines, then reprobation is the bogeyman. Alongside the Gospel of salvation, considering how God’s eternal plan includes the condemnation of some is difficult to say the least. Christ came into the world to save sinners, not to leave them behind (1 Tim 1:15). Christian piety begs to ask: If God is completely sovereign over creation (as we have repeatedly said), how or why are some not saved?

At this point, many apologists will begin to distinguish between “double” and “single” predestination. Unfortunately, in my discussions with well-read Calvinists (like Michael and Gabriel), Lutherans, fellow Catholics, or other Christians, I have found that these terms do not always have a consistent meaning.

The most common use of “double” predestination refers to the doctrine of John Calvin, and more specifically, to the manner in which God’s sovereignty extends over both those God saves and those who remain in sin (hence “double”). For example, the Reformer says, “God not only foresaw the fall of the first man, and in him the ruin of his posterity; but also at his own pleasure arranged it” (Institutes, Book III, Chapter 23.7, emphasis added). With such a statement, it is difficult to see how God would not be the author of sin, though Calvin vehemently denies the charge.

“Single” predestination refers to a plan that exclusively regards the saved. While it laudably avoids Calvin’s difficulty, a different question arises: What is God’s plan for everyone else? Leaving them to chance is hardly compatible with a sovereign God or even a sound philosophy.

Saint Thomas insists, as we have seen, that God’s sovereignty is universal, englobing both the just and the wicked. However, God’s transcendent, sovereign causality is not the same for good and for evil. Instead, it is asymmetrical. God positively wills good, including our justification, sanctification, and merits, but he only permits sin.

This is more than a quibble over words. When God positively wills something, he causes it. When he permits something else, he does not cause it. Permission here does not mean consent or agreement, but that God declines to prevent. Let me explain.

Think of the car whose engine, despite your impeccable key-turning, just will not start. What is the cause of the failure? It is not in the key-turning. That initial action in the chain of causes worked fine. Even if your key-turning technique could improve, there are a host of other intermediate causes necessary to produce that healthy engine hum. Maybe the spark plug failed, or perhaps the fuel injector is improperly installed. Whichever one of these fails is the real culprit. In fact, your key turning probably gave the spark plug some activation. Whatever spark it gave, though insufficient to ignite the fuel and start the engine, still came from the turn of the key. The key-turning produced the act which failed, but it did not cause the failure of the act.

Man’s sin occurs in a similar way. God, as Creator and Sovereign, is the primary and transcendent cause of man’s action, but God is perfect and indefectible. Man, though, is more than capable of being defective—that is simply part of being a creature. Whatever goodness man’s action possesses comes from God, but any defect arises because man’s cooperation failed in some respect. Just like your impeccable key-turning did not cause the spark plug’s failure, God’s governance enables our free will to act, but the disorder of an act is ours alone (ST I-II., q. 79, a. 2, co.; I., q. 49, a. 2, ad2).

The difference is subtle but important. Because man introduces the defect, man, not God, is the author of sin. God does not lead anyone to sin, but he does permit it by declining to prevent it. The case of the individual sin is a microcosm for understanding the causality of reprobation: God permits but does not cause the disorder of sin, and because man is guilty, he is justly punished (ST I., q. 23, a. 3, ad2).

Okay, so evil is not God’s fault… but why doesn’t he prevent it? Saint Thomas offers several answers which each boil down to the same conclusion: by the omnipotent wisdom and goodness of God, he is able to draw good even out of evil (ST I., q. 2, a. 3, ad1; q. 48, a. 2, ad3). Admittedly, it is an answer that hardly satisfies the mind, not to mention the heart. However, in order that we not become cynical, God proved his love for us: while we were yet sinners, Christ came to save us (Rom 5:8).

The fourth installment of Brother Elijah’s four-part reflection will be published on Wednesday, May 20.

✠

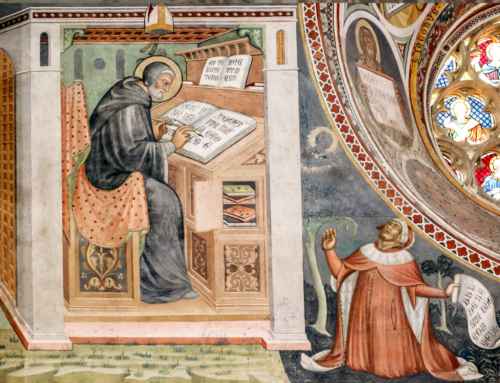

Image: Gustave Dore, The Inferno, Canto 32