Love of neighbor is none other than the extension of love of God. Hence, it is a question of one and the same love that is supernatural, theological, and essentially divine. In the soul of a religious this love is to become so intense and so ardent as to merit the name of zeal. For a soul consecrated to God it is a duty, an indispensable obligation, to nourish in itself zeal for the glory of God and the salvation of souls. Always it is a question, fundamentally, of the same zeal, of the flame of the one and same love.

—Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, O.P.

Souls Consecrated to God

I have often imagined what it would have been like to witness St. Dominic, the first of the Friars Preachers, walking through the heresy-ridden countryside of southern France some years after the turn of the thirteenth century. What was it like for the infant Order of Preachers to hear the prayers and supplications of its founder coming from the chapel throughout the night? How inspiring it would have been to witness the Preacher of Grace convert and win souls for Christ!

However a friar imagines such moments, when he returns to reality he is ultimately faced with the realization that the routine of religious life does not exactly shine with such obvious heroic sanctity. Rather, more often than not, we are our own witnesses to the brokenness of the human condition and to the drudgery of working for the salvation of souls, ours and others, in a world that often fails to recognize the reality of eternity.

However, there is a particular beauty and a real depth to a life consecrated, a life called away from itself and given to Christ and His Church. Individual consecrated lives, by and large, go unnoticed in the eyes of the world, with the exception of a handful of canonized saints.

My intention is not to comment on the successes or failures of a friar, but I would contend that serious reflection ought to be given to the example of those who have lived “the life,” to those who have, for all intents and purposes, followed in St. Dominic’s footsteps and left their marks in more hidden ways. Religious life, after all, is not a school of glamour, but a school of holiness—an often unappreciated path of trials and struggles, all to conform more assuredly to Christ.

A Brief Biography

Fr. Carleton Jones, O.P., is currently the prior of St. Dominic Priory in Washington, D.C. His life of faith is an interesting one, and perhaps his ministry is even more so. Fr. Carleton was born in 1943 in Louisiana but raised in Meriden, New Hampshire, where his father was a teacher at a boarding school. Fr. Carleton has an impressive academic pedigree, having completed his undergraduate studies at Yale University and having earned a doctorate from the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (the Angelicum) in Rome.

Fr. Carleton was ordained an Episcopalian priest in 1970. He was received into the Catholic Church in 1982. He entered the Dominican novitiate the following year, made his simple profession in 1983, and was ordained a Catholic priest in 1987. As a Dominican friar, Fr. Carleton has served as pastor and superior of a number of parishes and communities throughout our province, has been a chaplain to nuns, and has worked in various administrative roles.

In preparing to write this piece, Fr. Carleton gave me a copy of his curriculum vitae. Certainly it reveals his intense academic study and years of ministry to the Church and her faithful. Given that a document of this type focuses on academic credentials rather than pastoral experience, his CV naturally made no mention of a part of Fr. Carleton’s life as a faithful Catholic priest committed to helping others and leading them to the fullness of the Truth, namely, his work with homosexuals, or those who suffer with same-sex attraction.*

An Unanticipated Beginning

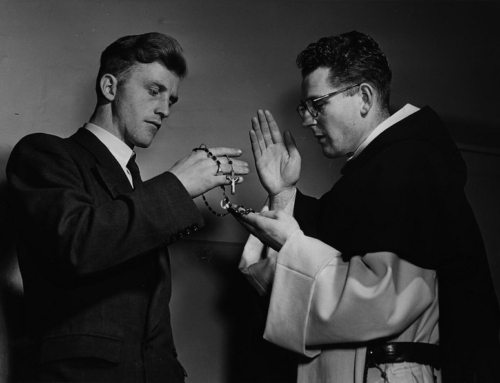

I make mention of the CV not to point out the esoteric or to nitpick, but because I think that this speaks exactly to the point that was made above. A life in pursuit of souls for Christ, more often than not, demands a sort of silent or unnoticed endeavor. Fr. Carleton’s work with same-sex attracted persons began in the late 1960s when he was an Episcopalian deacon in New Haven, Connecticut. At the time, there was a Lutheran minister running a support group for same-sex attracted Christians at Yale University. When the Lutheran minister was called away to another assignment, Fr. Carleton was asked to continue the group.

Fr. Carleton—then a young, unseasoned Episcopalian deacon with no experience in ministering to same-sex attracted persons—suddenly found himself trying to lead these individuals in a life of chastity and virtue amidst intense social pressures from the increasingly vocal gay community. He spoke to me of the way in which the Stonewall Rebellion in 1969, the first violent demonstrations of the gay community in New York City, following a police raid of the Stonewall Inn, affected the group. He recalled how a man came to speak at Yale calling for members of the gay community to publicly identify themselves and join this movement. This was the first time Fr. Carleton remembered the gay rights movement being likened to the civil rights movement, and this put tremendous emotional and psychological pressure on the members of his group to abandon the Christian virtues that they strove to live. Shortly thereafter, Fr. Carleton was reassigned. But, standing firm in his Christian beliefs, he strove to be a continued source of support for people struggling with same-sex attraction.

“Do You Not Want Me?”

It is always a rather noteworthy occurrence when a friar finds himself face to face with someone who has just experienced a radical conversion. Fr. Carleton found himself in this position twenty-five years after leaving Yale. At that time, Fr. Carleton had returned to New Haven, where he was assigned as pastor of the Dominican parish, St. Mary’s. Now, however, he was a Catholic priest. Fr. Carleton recounted the following story, not to showcase himself but to illustrate a powerful example of God’s grace at work.

There was a man in his mid-sixties who attended daily Mass but never received Communion. On one particular day, this gentleman did, in fact, receive the Blessed Sacrament. Fr. Carleton spoke to him afterwards and asked what had happened. It turned out that the man had been very active in the gay community in New York City for many years. But, being a Catholic, he always continued going to Mass on Sundays. After retiring from his work in New York, he started going to daily Mass but still never received Communion. This man told Fr. Carleton, “For forty years my conscience would not allow me to miss Mass, but my conscience would not allow me to receive Communion.” This was until he heard a voice ask him interiorly, “Do you not want me?” This man knew that the Lord was calling, made a confession, and received our Lord in the Eucharist.

After this, the two of them started a Courage chapter at St. Mary’s. Though the group was never large, it was full of people seriously committed to living a chaste life. Fr. Carleton worked with the group until being reassigned elsewhere in the early 2000s. It would be unfair to project onto the group any sort of falsely romanticized spiritual or emotional journey, though I think it is important to see God’s providence at work here.

The Dominican friar is one who ought to be able to move to a new assignment at any given time. It is not the individual man or his project that matters but his ability to be the Lord’s instrument in His providential plan. This was the case from the very beginning of the Order when St. Dominic sent the first small group of friars out from their convent in France to the university cities throughout Europe in August of 1217. Whom we meet in our lives and to whom we preach and serve is entrusted to the workings of the Holy Spirit through our superiors, not to our personal desires, however well intentioned they may be.

Over the Periphery

When I spoke with Fr. Carleton, he had many insightful comments about his experience working with same-sex attracted persons. He quoted Pope Francis’ expression that the “Church is a field hospital” through which people are healed by God’s grace. Fr. Carleton said that healing is not simply synonymous with becoming a heterosexual person. Father explained that there is more to it than a change in orientation. Healing, for anyone, also includes being able to integrate one’s wounds, to live with peace and happiness, and to be able to carry one’s cross.

I think that people, those who love the Church and those who are opposed to her, have strong opinions regarding the Church and her relationship to same-sex attracted persons. Popular debate has demonstrated that society often lacks a robust philosophical language with which to understand the concepts of nature, sexual complementarity, and teleology that the Church routinely uses. I had the opportunity to ask Fr. Carleton about his thoughts on this topic, and he explained that a lack of understanding does not mean that the truth ought not to be proclaimed, nor does it mean that people cannot understand this truth. Fr. Benedict Groeschel, C.F.R., writes,

True love has to be tough at times because it seeks something for the beloved that is beyond appearances and far more radical than the needs and hungers of the passing moment. For the Christian, love must consistently and ultimately be directed toward the salvation and sanctification of the beloved. True friendship seeks the best for one’s friend.

Ultimately, following Fr. Groeschel, Fr. Carleton stressed the importance of an honest, strong, loving presentation of the Church’s doctrine. Father made the point that same-sex attracted persons were often made to feel as if there was no place for them in the main body of the faithful and were made to feel like lepers. They were “over the periphery” of the Church, as it were.

Instead, as Fr. Carleton expresses it, we need to continue to develop a pastoral approach that “is fully respectful of their humanity, that doesn’t single them out as vile or dangerous or contagious, which doesn’t make the mistake of thinking that acting out one’s homosexual desires is a way to happiness, and is under no illusion about that, and that wants to help people see that you can live a happy life without sex.” Ultimately, this approach would pull people back over the periphery into a full and authentic relationship with Christ and His Church.

Fr. Carleton also commented on what might make a Dominican friar unique in ministering to same-sex attracted persons. One might assume that an answer would explicitly cite our life of study or our attempts at contemplation, but he offered something more subtle. He said, “The strength of [our] ministry and witness is always in its clarity and its lack of sentimentality.” Clarity, according to Fr. Carleton, is not the ability to put together a disputatio but the ability to proclaim the truth (i.e., Christ’s teachings as proclaimed by the Church) in a positive way and to offer real encouragement. He referred to a lack of sentimentality inasmuch as people who struggle do not want pity; they want Jesus Christ and what He has to offer. We must acknowledge the cross, embrace it, suffer under it, and be saved by it.

Following Silently

Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange’s quotation at the beginning of this piece is quite poignant, particularly for the friar. “In the soul of a religious . . . love is to become so intense and so ardent as to merit the name of zeal. For a soul consecrated to God it is a duty, an indispensable obligation, to nourish in itself zeal for the glory of God and the salvation of souls.” The name of the game is love: not self-love, but self-emptying love; a love that pours forth from a real relationship with Christ; a love that cannot be contained but that flows into whatever or, more importantly, whomever is in front of us.

The Church has consistently proclaimed that each person is created in the image and likeness of our God. In the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith’s Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons (1986), we read:

The human person, made in the image and likeness of God, can hardly be adequately described by a reductionist reference to his or her sexual orientation. Every one living on the face of the earth has personal problems and difficulties, but challenges to growth, strengths, talents and gifts as well. Today, the Church provides a badly needed context for the care of the human person when she refuses to consider the person as a “heterosexual” or a “homosexual” and insists that every person has a fundamental Identity: the creature of God, and by grace, his child and heir to eternal life.

In proclaiming this redeeming message, we are asked to follow the famous words of Pope St. John Paul II’s inaugural address in 1978: “Do not be afraid. Open wide the doors for Christ.” Fr. Carleton’s dedication to the people who struggle with same-sex attraction has been to do just this: to affirm their fundamental identity as children of God, to allow God’s light to illumine the brokenness, and to bring God’s healing grace into their lives.

This, however, is the silent ministry of the friar—a life given to the service of the Church, following Christ through St. Dominic. Following. Not leading. Not blazing a new path. But trusting in God’s providence and grace that, ultimately, it is His work that is to be accomplished. I would not want to limit Fr. Carleton’s work or efforts to one particular area, no matter how noble, as this would not do his story justice. I also do not think that it would be appropriate to set Fr. Carleton on a pedestal (and I think that he would agree). After all, that would defeat the purpose of my point. The lives of the brethren are lives that may only be fully understood and appreciated in eternity. Nevertheless, they are lives that strive to fulfill that “indispensable obligation, to nourish in itself zeal for the glory of God and the salvation of souls.”

To download a printable PDF of this Article from

Dominicana Journal, Winter 2015, Vol LVIII, No. 2, CLICK HERE.

Endnotes

* I choose to use the term “same-sex attracted” to describe certain persons with whom Fr. Carleton has worked in his ministry because it is the term the Catholic Church normally uses in her documents and because it reflects her understanding of the human person. It is not meant to be pejorative or offensive, and I recognize that not all who experience these attractions may identify with this label, preferring a different word choice.