I recently visited a hospitalized woman in her seventies. She was very sick and could eat nothing without pain. No one knew the cause of her illness. Nor was it known where she would go if she ever got out. She was in between living arrangements and, for lack of funds, had already failed to secure housing at a number of places. She had always been poor. Her father had left the family when she was a girl, so from a young age she had worked and helped to raise her younger brothers. Now she was in a similar situation, for her husband had died years ago and could leave her no financial support. Sitting with her, I was reminded that Jesus said, “Blessed are the poor,” and wondered about what he meant.

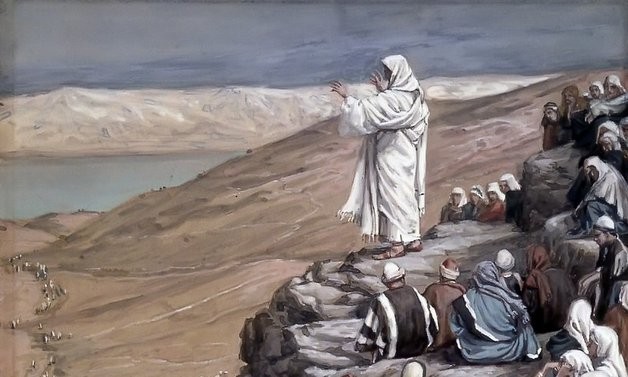

It was the first thing that Jesus said when he sat down to deliver the Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Mt 5:3). The qualification “in spirit” is not so much a relaxation of the counsel to be “poor” as a precision about its true significance. One can be materially poor and still be seriously sinful. And if mere poverty were blessedness, it would make no sense to give alms.

According to one major tradition of interpretation, “poverty in spirit” means humility, especially humble subjection to God. This is the habitual and lived recognition that without God we can do nothing. In fact, as creatures, without God we cannot even exist. Ours is a poverty not only of power but of being. And in Adam we marvelously declined to live in God’s garden and ended up hungering after the husks of swine—and no one would give us any (Lk 15:16). The poor man, the beggar, turns out to be an icon of the human being, seen in his ultimate context.

Maintaining this perspective is not easy. And here we catch another glimpse of why Jesus used the word “poverty” instead of “humility.” It is very praiseworthy to earn a living, to support one’s dependents, and to contribute to the Church and one’s civil community. But it is also true that the pursuit of money has the power to distract us from God, and the use of money threatens to inflate our sense of control and status. In short, it may happen that “the care of this world and the deceitfulness of riches choke the word” (Mt 13:22). As Jesus makes clear, the danger is surprisingly real: “Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” (Mt 19:24).

When the disciples responded despairingly, “Who then can be saved?” Jesus assured them, “With men this is impossible, but with God all things are possible” (Mt 19:25-26). In the knowledge of Christ, it is possible for the prosperous man to subject all money matters to God—to make mammon serve him!—to tithe, to support one’s family, to give alms, and in general to live with an appropriate simplicity. Intimate knowledge of the riches of Christ gives the lie to the idea that money can make us totally self-sufficient, or that worldly success will plead our case on the day of judgment.

If riches make us forget our utter dependence on God, the lack of riches makes us remember. This is part of the blessedness of being poor. But material poverty has its own problems; in particular, it can lead to despair. Again the answer is Christ. Though he was rich, he became poor, to bestow his divinity on those who trust in him.

At the end of our discussion in the hospital, the bedridden woman looked back on her difficult life and echoed St. Paul: “I count it all pure joy.” And I think it likely that she did.

✠

Image: James Tissot, The Beatitudes Sermon