Editor’s note: This is the ninth post in our newest series, Beholding True Beauty, which consists of prayerful reflections on works of sacred art. The series will run on Tuesdays and Thursdays throughout the month of October. Read the whole series here.

“The architect put sculptures of judgment, demons, and damnation … that way the pilgrims would be terrified and put more money in the collection plate.”

This was my architecture history professor’s summation of the portals of high gothic cathedrals. Those sculptures of Christian imagination were nothing more than morose shakedowns of pious grandmothers walking on their knees.

Balderdash!

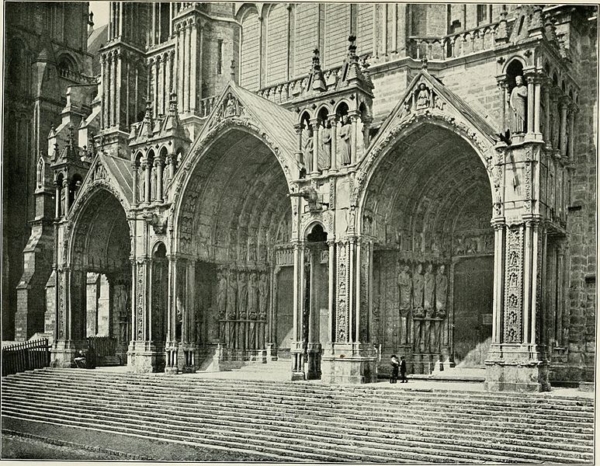

Otto Von Simpson—an astute architectural historian—described Chartres Cathedral, Notre-Dame de Chartres, as an economic effort unrivaled by any contemporary undertaking. The material sacrifice of the people of Chartres serves as a “crude yardstick” that can measure the spiritual importance of the cosmos in stone. Henry Adams, grandson and great-grandson of the American presidents, stated, “Half the interest of architecture consists in the sincerity of its reflection of the society that builds.” Rather than reflecting a French Halloween House of Horror that mugs mémé for a few extra livres, The Last Judgment over the southern doors of Chartres reflects a society of towering aspirations. Higher than the two towers of its west facade, the aspirations of the anonymous architects, masons, and benefactors soared toward their goal: to be a saint and enter heaven.

Photo by Internet Archive Book Images

The southern porch of Chartres projects off the main body of the Church, creating a safe haven from the sun, rain, and wind. The porch is a refuge for tired pilgrims wishing to pray in thanksgiving for having arrived to their destination. This cathedral dedicated to Our Lady receives and protects pilgrims like the Blessed Mother safeguards sinners. She is the refugium peccatorum.

Photo by Seudo

The ancient steps, worn and laden with the feet of millions of pilgrims, rises from the profane square toward the sacred interior. The portal summons the visitor to ascend, approach, and enter the way to eternal life. The whirling bands of archivolts pivot on the central tympanum as they step inward toward the doors, pulling the visitor with them. The tympanum is Christ seated in majesty, judging the living and the dead, who are rising from their graves throughout the piece. Christ anchors the orbit of the twirling clouds—hosts of angels crying out “Glory to God in the highest.”

Photo by Nina Aldin Thune (CC BY-SA 2.5)

The lintel underneath his feet shows the judgment that must take place before one enters into heaven. The blessed move to his right and the damned move to his left. The unhappy souls, having refused Christ’s mercy in life, march toward the ravenous, serrated jowls of hell. Ghoulish demons strip their trembling, naked victims of worldly vestiges of honor. Robes, collars, and crowns do not save one from eternal punishment. All men and women must question their life and the state of their souls as they approach the entrance to the cathedral.

Photo by Seudo

The archivolts to the right, Christ’s left in the scene, show the dead rising from their graves, and the damned with their own special demon. The beasts carry their prey over their shoulder like hunted game slain in the forest. The frightful figure on the far right wags his furry tail, and his belly smiles as it contemplates its eternal meal. Yet, this scene, which is no laughing matter, possesses a sense of joy and levity imbued throughout the architecture.

Photo by TTaylor (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Terror does not have the last word in the composition. In truth, it encompasses less than a fifth of the scene. The just appear on the left, the right of Christ enthroned. The dead rise from their graves in praise and thanksgiving. The happy souls walk with the benevolent angels, and there is even the Bosom of Abraham (Lk 16:22–23), the ancient depiction of the righteous blissful rest. The faithful rest in the arms of the father of faith, Abraham. This scene continues above as the angelic choirs circle the scene in splendor and glory. One who looks up sees not just punishment and gloom, but the splendor of the saints.

Photo by TTaylor (CC BY-SA 3.0)

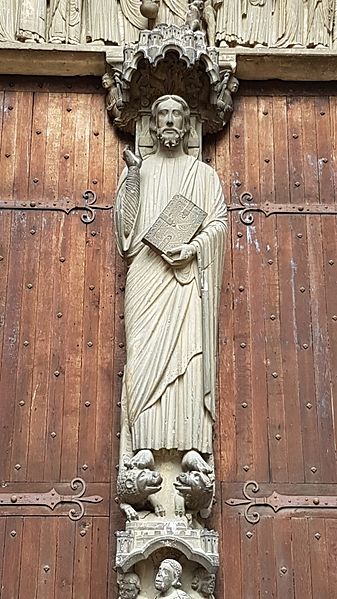

Centered between the doors, supporting the celestial scene above, is the trumeau with its figure, Christ Beau Dieu (handsome God). A court of saints, the apostles, flank him. Each jamb figure participates in Christ’s foundational role as they support the archivolts above. Their architectural mirroring of Christ strengthens their cruciform mirroring of his life. They each hold the instruments of their own passions, reflecting Christ’s own passion.

Photo by Seudo

Walking up to the Beau Dieu, one sees him standing upon the lion and dragon (Ps 91:13). The lion, according to St. Augustine, represents the devil’s raging persecutions, and the dragon represents his slithering lies of heresies. Artfully, the portal to the left of this central portal is that of the martyrs, champions like Christ over the lion. To the right is the portal of confessors, witnesses to the truth, and St. Nicholas, a saint who slapped the arch-heretic Arius, the dragon.

Those are portals worth a visit in their own right, but here the central figure grabs our attention. Christ, the handsome God, holds with one hand Scripture while he blesses with his other (a detail eroded away). Yet, despite the wages of time, the work communicates the beauty of God who welcomes the weak and weary into his Church. Before the door opens, the viewer beholds the one who stands at the door and knocks (Rv 3:20). The last view of this portal is not the terrible, but the beautiful.

Passing through the portal, the pilgrim is transported to a new world and witnesses the artistic expression of heaven upon earth. This artistic expression, according to Adams, is “a child’s fancy; a toyhouse to please the Queen of Heaven” meant to make her smile. No, it’s not terror that causes the pilgrim to give, it’s gratitude for being welcomed to the halls of the saints.

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

✠

Photo by Pseudo