Nobody likes to look like a fool, especially not a Dominican. Sure, it can be fun to play the buffoon for a bit to get a laugh or to make a point as long as when the dust settles it’s perfectly clear that our ignorance was feigned. Those unfortunate situations when we get caught with our proverbial pants down usually lead to intense brooding and a frantic review of what mistake could possibly have left us looking so naïve. These moments can be educational and formative in many respects, sharpening our mental acuity and keeping us on guard against making the same mistake in the future. When applied to intellectual pursuits, this discriminating eye can help us obtain a clearer vision of the truth. A danger arises, however, when we turn such a sharp instrument on our brothers.

This danger is not something unique to religious life. Regardless of our state in life, we are wary of being made to look foolish in our interactions with others. At face value this seems perfectly reasonable. Our relationships should be built on truth. Therefore, it seems that whenever we misjudge our relationships by uncritical assumptions we risk ruining that foundation. Unfortunately, it is never that simple. Our judgments are all too often weighted, and not in our neighbor’s favor. Sigrid Undset puts it quite clearly in her essay entitled, “To St. James: Proposal for a New Prayer,” in which she rails against the gossip and calumny that she saw rampant in her own day. She rhetorically asks:

And don’t you know the type of person who—innocently, I was going to say, if it were not just the opposite—considers it a mark of intelligence to be suspicious and a mark of naïvety to insist that one ought to believe the best, until one has certain evidence of anything worse?

If our neighbor falls short of our high expectations, that foolish feeling can creep in, and we begin to question the faith we put in them to begin with. On the other hand, if we presume the worst and our neighbor turns out to be quite innocent, we are not made to feel foolish; rather, we are pleasantly surprised. Why wouldn’t any reasonable person weight their expectations of future results based on past performance? And why would anyone presume the best when the past performance of man in this fallen world warrants low expectations? We can convince ourselves that we are not really judging our neighbor, which would clearly be out-of-bounds, but simply being honest about how they, and people in general, tend to act.

While this tendency to presume less of our neighbor may seem to have become particularly acute in our day, it is not a new phenomenon. In the earliest days of the Order of Preachers it was seen as something so divisive that it had to be nipped in the bud as soon as possible. In our Primitive Constitutions, implemented only a few years after the Order’s founding, there is an extensive section on the role of the novice master in the formation of novices. In addition to practical lessons concerning the life and liturgy of the Order, the master was charged with teaching the novices to presume the best of the brethren:

If they see anyone doing something, even though it appear evil, they shall suppose that it is good or done with a good intention, for human judgment is often deceived.

Surely this is much further than most of us are usually willing to go. Nevertheless, it is a valuable lesson that should accompany us beyond the novitiate and guide us in our daily social interactions, including when friars must give fraternal correction out of either charity or justice. Always presuming the best of intentions on the part of someone who seems to be (and in fact may be) doing something wrong, may appear foolish. But, however familiar we are with the fallen human condition from our own faults and failings, is it not better to risk looking the fool than to dwell on the presumed malice of our neighbor?

✠

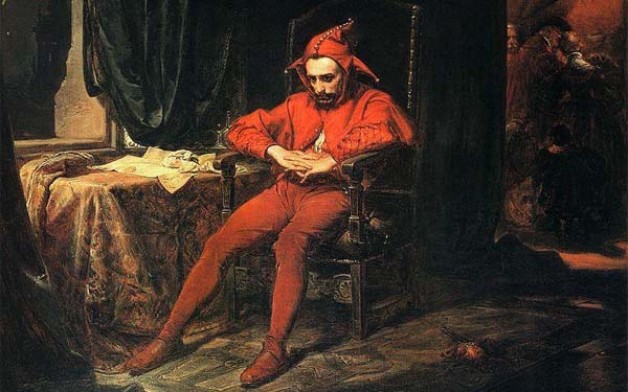

Image: Jan Matejko, Stańczyk during a Ball at the Court of Queen