The Christ-child was born “toto orbe in pace composito”—”in a world completely composed in peace.” Thus has the Roman Martyrology heralded the Christmas message year after year for centuries. Yet while the world looked so calm and composed on the outside, deep tensions lay under the surface, ready to burst out at a moment’s notice.

At the very heart of the world, peace was sought, but never quite found. In 63 B.C., as the Christ-child’s birth drew ever nearer, the masterminds of worldly peace were hard at work; Cicero rose to the Consulate, Rome chose Julius Caesar for her pontifex maximus, and the great general Pompey extended to Jerusalem the offer of the Republic’s peace. But, as it would turn out, neither rhetorician, nor high priest, nor general could bring about true peace. The peace offered was—as it always seems to have been—a cheap peace bought at the great price of war and death. Rome’s own national poet, Vergil himself, recognized the situation years later as a new empire emerged, the very empire into which the Christ-child would be born (Luke 2:1), the empire of Augustus. It was this regime that, Vergil observed, had well honed her arts: namely “to impose the rule of peace, to spare the subjected, and to war down the proud” (Aeneid, VI.851-853). The peace that Augustan Rome had on offer was like Cicero’s, Caesar’s, and Pompey’s; it was simply the quiet after the war.

Jerusalem, whose very name rang of peace (shalom), had long been awaiting true peace. But peace seemed about as far from the holy city as it did from pagan Rome. At the birth of the promised prince of peace, Herod the Great “was greatly troubled, and all Jerusalem with him,” for men had come from the east seeking “the newborn king of the Jews” (Matt 2:2–3). Herod, just like the other Roman leaders, had his own plans for peace—plans that didn’t include any newborn kings. So he would get rid of this newborn king, or do his best to try. He sent men to Jerusalem, and “a voice was heard in Ramah, . . . Rachel weeping for her children” (Matt 2:16–18). And then, all was quiet; all was calm. For terror always brings silence.

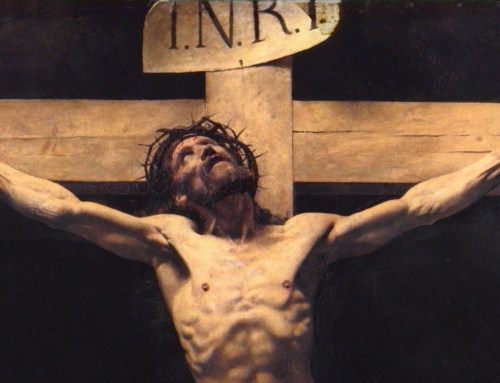

But, like the tyrant Herod, or like the men of Rome, the newborn infant had plans of his own. He too would march on to conquer nations and lands by his word, his sacrifice, and his deed. But he would do so unlike any rhetorician, priest, or general had ever done before. The hymn for Christ the King puts it so well: “For not by slaughter, force or fear / Did he subject his kingdoms here; / But, raised upon the tree on high, / By love alone he drew all nigh” (Hymnarium O.P.: “Vexilla Christus Inclyta”).

This king is born to establish a peace stemming not from fear, but from love. And, what’s more, the prince of peace comes to us again, just as he did in Bethlehem. He came long ago, as the Martyrology tells us, to be born “toto orbe in pace composito”—”in a world completely composed in peace.” Now, he comes again, to be born anew in what we might style “toto corde in pace composito”—”in a heart, completely composed in peace.” The heart in which the Christ-child comes to be born is similar to that world he came to be born in; it is a heart that appears so calm and composed on the outside, but that, under the surface, is subjected to, and warred down by, force and fear. This heart is your heart and mine. This heart is the heart of every Christian, who ever needs, and longs for, Christ’s gift of peace. The king of peace is coming. Let us cast aside our own plans for peace, and open wide our hearts for him, so that he can conquer these hearts of ours with his love, quiet them under his rule, and subject them to his peace. Then, and only then, will there be true peace, peace “that surpasses all understanding” (Phil 4:7).

✠

Image: James Tissot, The Adoration of the Shepherds (Wikimedia Commons)