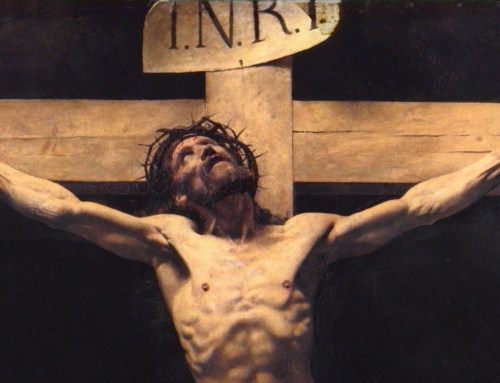

Everyone knows who Jesus is. He’s that great man who taught his followers to love their enemies and warned them not to judge. He spoke truth to power, and he paid the price for it. He loved the outcast and dined with sinners. This is the Jesus we all know and love.

But this portrait, true as far as it goes, turns out to be rather flat. Most people agree that we should love one another. And everyone supports speaking truth to power. If Jesus taught only what everyone already knows, he really has nothing to say to us.

In fact, however, Jesus’ teaching on truth and love is far from common knowledge. It’s true, for example, that he instructs us to love our enemies, but he also says—admittedly, by way of hyperbole—that we should hate our parents out of love for him (Lk 14:26). And his own love for the Pharisees did not prevent him from describing them as the rankest filth (Mt 23).

He also called them “hypocrites” and “a brood of vipers”—even though he instructed his disciples not to judge (Mt 23; 7:1). Apparently (and obviously), Jesus did not mean to rule out all moral denunciation. In fact, when Jesus discourages the man with the beam in his eye from removing the speck in his neighbor’s, he advises him to remove the beam in his own eye in order better to remove the speck in his neighbor’s (Mt 7:3-5). So, according to Jesus, to pass judgment on another’s immorality is to do that person a favor!

Given all Jesus’ criticism of the religious authorities, people sometimes infer that Jesus was against hierarchy or any organized religion. But of course he himself chose twelve men to succeed him in teaching the world, and he gave them power to decide things concerning heaven and earth (Mt 28:19; 16:19; 18:18). In fact, what Jesus acknowledges as good in the Pharisees is precisely their official capacity. Despite the Pharisees’ egregious wickedness, Jesus tells the people to listen to them because they sit on the seat of Moses (Mt 23:2-3). That is about as ringing an endorsement of organized, hierarchical religion as one could find. Not that the Pharisees are necessarily better than everyone else. Jesus saves his highest praise for the humble: “whoever humbles himself like [a] child, he is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven” (Mt 18:4). According to Jesus, humility and hierarchy go together. Even in heaven, human beings will be arrayed in order of greatness.

Nothing in Jesus’ teaching is self-contradictory (unlike Walt Whitman, Jesus did not consider self-contradiction an expression of wisdom). Instead, the teaching of Jesus is paradoxical, because life itself is paradoxical. Only a doctrine that is profound and perplexing is adequate to the mystery of human life. And only a teacher who is surprising, strange, and strong can demand our full attention. If we content ourselves with anything less, we lose the real Jesus. We get a cardboard-cutout Jesus, who can be little more than a confirmation of our own prejudices.

And really, it is Jesus’s teaching about himself that is at the heart of his message. Unlike the Buddha, for example, Jesus did not instruct his followers to ignore his person and focus on his teaching. In the center of Mark’s Gospel, Jesus asks his disciples the central question: “Who do you say that I am?” (Mk 8:29). In John’s Gospel, he answers his own question: “He who has seen me has seen the Father” (Jn 14:9). It is this paradox, the mystery of Jesus’ true humanity and true divinity, that is the source and explanation of all the other paradoxes of his doctrine. All the other paradoxes lead back to this one. And it is this mystery of Jesus’ identity that makes his teaching infinitely worth hearing.

“Let him who has ears to hear . . .” (Mt 11:15).

✠

Image: DyeHard, Cardboard Model Landship