Editor’s note: This post, originally published on November 28, 2011, is the first in a series on the Book of Revelation. You can read the whole series here. Fr. Leo Checkai was ordained a priest in May 2014 and now teaches at Providence College.

We speak a wisdom to those who are mature, but not a wisdom of this age, nor of the rulers of this age who are passing away. Rather, we speak God’s wisdom, mysterious, hidden, which God predetermined before the ages for our glory…

—1 Corinthians 2:6-7

The Book of Revelation, or The Apocalypse of St. John, is a book full of mystery. Indeed, St. Jerome famously observed that the Book of Revelation has as many mysteries as it has verses. But to one who is willing to read the Book of Revelation and the rest of the Holy Scriptures with the eyes of faith, that is, to read them in the same Spirit in which they were written, these mysteries are not impenetrable, since the Word of God itself gives us many helps toward entering into the mysteries.

The season of Advent looks toward Christ’s Second Coming in a particular way as we reflect on the glorious Incarnation and the enduring presence of the Lord in our lives. Throughout this season I will be offering daily posts examining the Book of Revelation, sharing some principles by which each of us can read the Book fruitfully ourselves as a means of entering more deeply into the mysteries of the Incarnation.

Accordingly, the posts in the beginning of this series will be dedicated to learning from Scriptural examples how to interpret the kind of Biblical literature to which the Book of Revelation belongs. The next posts will focus on passages of the Old Testament that unlock particular passages of the Book of Revelation. To complete the series, we will embark together on a reading of the Book of Revelation itself, putting into practice what we have learned.

In our society today there is so much sensationalism surrounding the Book of Revelation, so many bold yet contradictory claims to knowledge, that I hope you will bear with a bit of a preamble for the sake of ensuring a sound, well-founded, and profitable reading free from baseless speculation, so as to be on course toward entering into the true mysteries of the Book of Revelation.

Bear with me if this first post seems a little dry. But when seven-headed beasts and antichrists start flying around, we’ll want to have our principles firmly in place.

Successful communication between author and reader requires that the reader bring certain things to his reading of the text. For instance, if it is a text written in English, the reader must bring a knowledge of the English language. If you are attempting to interpret this text on the assumption that I am writing in French, you must be very confused by now. This principle goes well beyond mere grammar, however—for instance, if you are trying to interpret this piece as a humor column, you must be very disappointed by now.

Even if the reader does not bring the things the author expects, however, he may manage to produce an interpretation that has some degree of internal consistency. With the text of a human author such a reinterpretation may have merit, because the reader’s ideas and his creative use of the text may be better than the author’s ideas and his purpose in writing. But this cannot be the case with divinely authored texts, where we must follow the intent of the author. This “constraint” upon our reading does not so much limit us as free us to discover God’s revelation to us, a message which is marvelous beyond anything we could have made up by our own cleverness.

Since the point of the Holy Scriptures is for God to reveal his message to us, to read them successfully we must approach them with the things that allow us to receive that message. For the Book of Revelation these things are, chiefly, a lively faith that seeks to understand and an intimate familiarity with the Old Testament.

St. Augustine observes in his book On Christian Doctrine that there are many ambiguities of language, even in Scripture, that cannot be resolved by one’s knowledge of grammar, no matter how knowledgeable one may be. In such cases one must interpret according to the rule of faith. This means not just any religious belief that people call “faith,” but the divine and Catholic faith that comes to us by virtue of the same Holy Spirit who inspired the sacred author.

The Vatican II Constitution on Sacred Scripture Dei Verbum provides us with guidance on what a faithful reading involves:

§ 11. Those divinely revealed realities which are contained and presented in Sacred Scripture have been committed to writing under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit…In composing the sacred books, God chose men and while employed by Him they made use of their powers and abilities, so that with Him acting in them and through them, they, as true authors, consigned to writing everything and only those things which He wanted.

§ 12 Since God speaks in Sacred Scripture through men in human fashion…to search out the intention of the sacred writers, attention should be given, among other things, to “literary forms.” For truth is set forth and expressed differently in texts which are variously historical, prophetic, poetic, or of other forms of discourse. Since Holy Scripture must be read and interpreted in the sacred spirit in which it was written, no less serious attention must be given to the content and unity of the whole of Scripture if the meaning of the sacred texts is to be correctly worked out. The living tradition of the whole Church must be taken into account along with the harmony which exists between elements of the faith.

This conciliar document on divine revelation teaches us a great deal, including these three key truths:

1. that faith receives the Scriptures as the Word of God;

2. that we should be attentive to the literary form in the Scriptures;

3. and that we should be attentive to the Spirit by whom the Scripture was written, through considerations of the content and unity of the whole of Scripture, the living tradition of the whole Church, and the analogy of faith.

Concerning literary form, we see that the Book of Revelation contains internal cues about what kind of literature it is. It repeats five times that it is prophecy or prophetic message (Rev 1:3, 22:7, 10, 18, 19). Furthermore, comparison of Revelation with other books of the Bible shows extraordinarily extensive reference to the Old Testament, with a strong likeness to books and passages of the Old Testament that are clearly prophetic.

If you know the Old Testament, then you can tell by reading the Book of Revelation that whatever language you are reading it in, whether Greek or English or Latin or Spanish, the “language” it is really written in is “Old Testament.” Since St. John and the early Christians to whom he wrote knew the Old Testament as well or better than we know our favorite TV shows and movies, it makes sense that God would give him visions that used images from the Old Testament. Almost every verse in the Book of Revelation has an allusion to an Old Testament passage, and many of them have several.

Therefore, in order to learn how to interpret the Book of Revelation rightly, we ought to read it in the context of the whole Bible, with special attention to prophecy from the Old Testament, and apply what we learn under the guidance of the rule of faith.

Now, we can’t expect the pope to do all our thinking for us, because that’s not his job. But we can expect the pope and the Church’s magisterium to give general guidelines and set bounds by ruling out specific errors. That way we are freed from running headlong into serious error and so can exercise our powers of thought upon the text.

For this we need a lively faith ourselves, and an intimate familiarity with the Old Testament. Or if we do not have the latter yet, a willingness to delve into it and learn. I hope that we will discover together just how fruitful such a reading can be over this Advent series.

The next post in this series is here, and you can find the whole series here.

✠

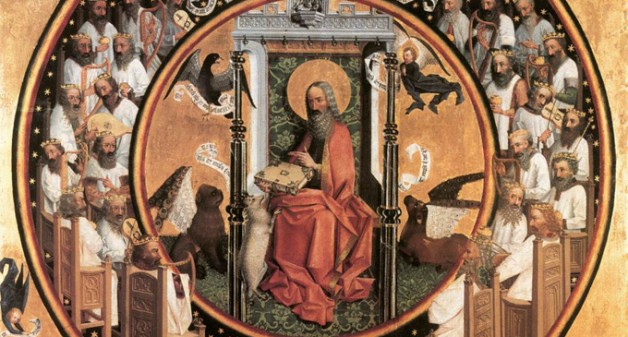

Image: Unknown German Master, Vision of St John the Evangelist