Lectio Divina: A Meditation on the Gospel for Sunday

With the Gospel reading from the upcoming Sunday Mass as its principal source-text, each Lectio Divina (“Sacred Reading”) essay offers a prayerful meditation of the Sacred Scriptures—one which draws from the wealth of biblical literature, as well as the prayer life of the individual author.

It is Easter afternoon, and death has been defeated, but the news goes unknown and unheeded. The world is mute and aghast. The reputed Messiah has been crucified; what now?

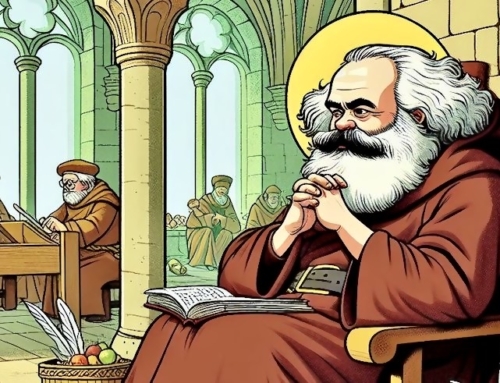

The Gospel’s first line should give us pause: two of Jesus’ disciples were going to a village seven miles from Jerusalem called Emmaus. Mount Zion, the Lord’s “holy mountain,” is God’s dwelling place, built “strongly compact” (Ps 2:6, 122:3). The disciples, however, are on a descent—both topographical and spiritual—from this very city, the city of God. They are going the wrong way; they have left behind their hopes in Jerusalem.

He drew near and walked with them. Jesus, as he always does, makes the first move, approaching the fugitives—approaching us—without intrusion. But, their eyes, the eyes of their mind, were prevented—the Greek is from krateo, literally “held back” or “arrested”—from recognizing him. They behold a man but do not yet see in him the God-man, for Christ, as with the Magdalene in John 20:11-18, has still more to reveal to them—and always, according to his wisdom, to evince “the mystery of the Father and His love” (Gaudium et Spes 22).

“What are you discussing as you walk along?” … “What things?” The Lord knows, of course, but wants them to render an account, to reason with him—to explicate the meaning of the weekend’s events. They, downcast, are not up to the task. Their hope was in a prophet mighty in deed and word (like Moses, cf. Acts 7:22), who would be the one to redeem Israel and reign from David’s throne unto the ages. But it is now the third day since the chief priests and rulers … crucified him. Death remains the apparent king.

Alas, they conceive of the wrong throne. They speak correctly when they call Christ a “visitor” (paroikeis, more literally, “foreigner” or “stranger”), but they know not what they mean. For he is the visitor who came forth from the Father and entered “into what was his own” (John 1:11) to manifest a “kingship not of this world” (John 18:36).

For their culpable unknowing, they earn a rebuke: “Oh, how foolish you are! How slow of heart to believe all that the prophets spoke! Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” Saint Jerome teaches, “ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ.” The Lord affirms the converse: knowledge of Scripture is knowledge of Christ. Beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them what referred to him in all the Scriptures. Every single thing that transpired, dating to Eden, “did not just simply turn out but came forth from the predestined purpose of God” (St. John Chrysostom).

As they approached the village … they urged him, “Stay with us, for it is nearly evening and the day is almost over.” God takes our littlest gestures of love and makes them occasions for salvation. “Where charity and love abide, God is there” (cf. Ubi caritas chant).

So he went in to stay with them. And it happened that, while he was with them at table, he took bread, said the blessing, broke it, and gave it to them. (“Took,” “blessed,” “broke,” and “gave”—the same four gestures of the multiplication of the loaves and the Last Supper.) With that their eyes were opened and they recognized him—cf. “it is the Lord!” (John 21:7)—but he vanished from their sight. Yet he departed only in bodily form, for he remained nonetheless present, then as now, under the form of the bread.

Then they said to each other, “Were not our hearts burning within us while he spoke to us on the way and opened the Scriptures to us?” We cannot love what we do not know (cf. Augustine, De Trinitate, X.1.2). The Word (the Son) illumes their minds, and his Love (the Spirit) impels their hearts. They become furnaces of charity, burning on the inexhaustible fuel of grace.

So they set out at once—the Greek here is from anistanai, “to rise up,” the same word that describes Christ’s resurrection—and returned to Jerusalem. Then the two recounted to the others what had taken place on the way and how he was made known to them in the breaking of bread. This reaction is at once Christic and Marian. They, on the pattern of Christ, have been raised to new life. And like two Marys filled with glorious news—the Mother of God after the Annunciation and the Magdalene after the Resurrection—they cannot contain themselves. Converted, they make an about-face toward Zion and dash off to announce: the Lord is victorious. Alleluia!

✠

Image: Jan Wildens, Christ and his Disciples on the Road to Emmaus