The water that I shall give him will become in him a spring of water welling up to eternal life. (John 4:14)

Reflecting on the hundreds of thousands of participants in the National March for Life today, there’s a question worth asking: How can a Christian really be pro-life?

After all, Christians believe that this vale of tears is going to end, that Jesus promises a better world hereafter, and that we need to have our hearts set on it alone. We are told, “Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, love for the Father is not in him” (1 John 2:15). The first Christians eagerly prayed for the end of this world, as we see in their liturgical prayers: “Let grace come, and let this world pass away” (The Didache 10). Our Lord promises eternal life, but has some startling demands to make of his disciples about this life: “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his own father and mother … and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple” (Luke 14:26). Even his own life?

“Hate” here clearly doesn’t suggest wishing evil to one’s relatives, or to anyone else. A few chapters earlier, Jesus explained that love of God and neighbor is the way to eternal life (Luke 10:27-28). “Do this,” that is, love, “and you will live” (Luke 10:28). But the life Jesus promises, the life we anticipate for others, is eternal life, a new life after death. What about our present life? Does Christianity protect life as part of a moral code (e.g., “thou shalt not kill”), only to tolerate it as a series of detours between us and heaven?

Immediately we should affirm that this life has its own value, even apart from religious arguments. Saint John Paul II, in his encyclical Evangelium Vitae, emphasizes that human reason can accept the basic arguments against the culture of death. All can “recognize in the natural law … the sacred value of human life from its very beginning until its end” (Evangelium Vitae 2). Groups such as “Secular Pro-Life” or even “Atheists for Life” will march today alongside Christians. These men and women can see, by accepting a true anthropology, that the unborn, the elderly, and the vulnerable have value and rights. In Genesis, we find the same affirmation that human life is good, even “very good” (Gen 1:31). To hate life in this world, to presume it is an evil, contradicts both a true knowledge of ourselves and God’s word from the beginning of time.

In truth, Christian longing for our future life doesn’t diminish the life we live now—it elevates life to its full dignity. As John Paul writes, “Man is called to a fullness of life which far exceeds the dimensions of his earthly existence, because it consists in sharing the very life of God. The loftiness of this supernatural vocation reveals the greatness and the inestimable value of human life even in its temporal phase” (EV 2, emphasis added). God “so loved the world,” this world, that he sent his Son to die for our sins (John 3:16). This truth drives our commitment to the Gospel of Life: “The blood of Christ, while it reveals the grandeur of the Father’s love, shows how precious man is in God’s eyes and how priceless the value of his life” (EV 25).

Life on this earth cannot be our lasting happiness; in this sense we are to “hate” it, putting it absolutely second. All the same, the Incarnation’s gratuity puts everything in the divine perspective, so that these years of human life on earth take on an infinite significance. No, you don’t have to be a Christian to be pro-life. Nevertheless, the Son’s redemptive death gives us the greatest of all possible reasons to love and cherish every human life—for every human life has been loved and cherished by God.

✠

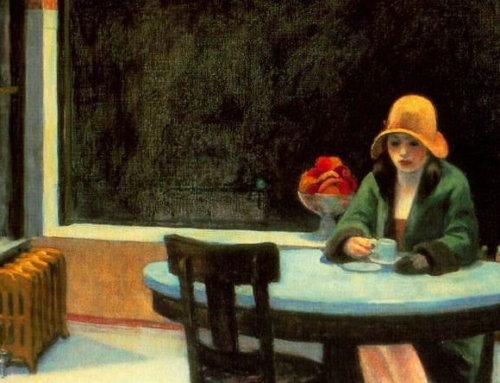

Image: Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)