Notes for preaching re: Solemnity of SS. Peter and Paul, June 29th:

Step 1. Summarize/repeat Gospel passage.

Step 2. Note: Peter wasn’t always the Pope. Recount various Petrine foot-in-mouth episodes. (NB: Great potential for laughs/comic relief.)

Step 3. Note: Peter is not so different from us, etc. Encourage listeners to relate and identify.

Step 4. Point out that, just as with Peter, God has a plan for each of us despite our own shortcomings. Reference invitation, conversion/metanoia, mystery, grace (?).

[NB: If time permits, rinse and repeat, inserting Paul-as-converted-radical.]

This sort of homily is about as rare as a Dunkin’ Donuts in Boston. Also like Dunkin’, and pace New Englanders, it’s not enough to live on. The problem with it is not so much that it says anything blatantly false, but that it is so fixated on the fact that God exalts the lowly that it totally glosses over the fact that they are exalted. Because it’s so heavy-handed with the assurance that Peter and Paul are not so different from you and me, it can get awful hard to see why they’re such a big deal. Even worse, it leaves the whole process by which the loudmouth loser becomes the saint in the dark. How do they get from point A to point B?

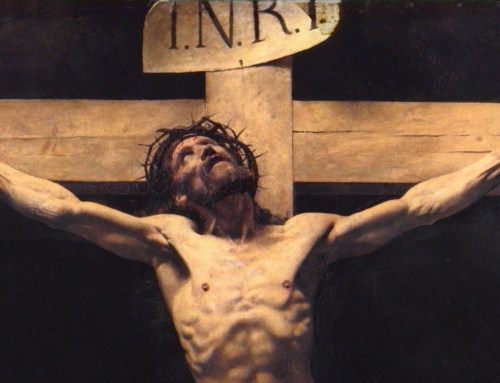

For a different view of Peter and Paul, picture for a moment their towering statues in front of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. They are, of course, larger than life: great hulking sword-and-keys-clutching behemoths. In a roughly similar sort of way, saints’ lives can generally loom too large for us to take in their full significance. So we stress the similarities rather than the differences. Peter is a loudmouth, and Paul, well, he can’t write a decent, succinct English sentence for the life of him. This is mostly a move to make these Olympians relatable, to remind us that they were flesh-and-blood like us. It’s because we’re easily discouraged by the distance separating us from the holiness of the saints that we try to avoid making holiness seem too remote or too distant.

As far as that goes, that’s all well and good. Sometimes, however, the gritty-reboot hagiographies and anyone-can-be-holy sort of approach can distort our perspectives of the saints, so that instead of looking up to St. Paul towering above me, I end up finding or refashioning more “realistic” goals and guides. And that’s when things get dicey and I get nervous and start quoting George Weigel. In a wonderful throw-away line, Weigel once wrote that our culture suffers under the “tyranny of diminished expectations.” This skewers the confusion lurking in the way we often view the holiness of the saints. It’s no good “imitating the saints” if by that we mean arbitrarily reducing the lives of the saints to more everyday, “relatable” proportions. We’ve just diminished our expectations of what the Lord will do in our lives.

The point of the massive statues and monumental depictions is not to emphasize distance for the sake of distance, as if to remind us how puny and spiritually anemic we are. It’s to move us to reflect on the height of glory to which we’re called, as well as the power of God that lifts us up to said heights. This, I think, is what Paul is driving at in Eph 4:13 when he talks of attaining to “the full stature of Christ.” The grace of God doesn’t make heaven habitable for humans–it makes humans fit to inhabit heaven.

All this boils down to a question of hope, the virtue that looks the bonum arduum, the difficult good, square in the eye and takes it on. “The one who has hope,” Pope Benedict XVI wrote, “lives differently; the one who hopes has been granted the gift of a new life.” Whoever has been given a new life sees the world afresh, alive with possibilities. The virtue of hope is about expanded, not diminished, expectations of what the Lord can do. It is about being prodigal in our spending, not on ourselves, but of ourselves. The hope of Saints Peter and Paul–apostolic hope–is about abandoning the anxious and penny-wise budgeting of our energy and resources. It’s not a matter of dreaming big, but of living large–living beyond our means, in a sense. The apostles, in short, are the biggest moochers. Their lives are irresponsible, profligate, completely unsustainable in the world’s eyes. They live beyond themselves. Think of Peter leaping out of the boat to meet Jesus on the shore, and the wild abandon of Paul’s preaching trips around the Mediterranean. Where did they get the nerve to live this way?

The lives of Peter and Paul have their significance and magnitude only by the hope born of their encounter with Jesus Christ. They met him while boisterous, proud, selfish, cowardly, vain; in this regard, they were as we are: too narrow and too small for the greatness of God. Only the grace of God can open our dinky hearts to receive love and to love with boldness.

So where do we put our trust? Not, the Psalmist is at pains to remind us, in chariots, horses, princes, or any mortal man, for that matter. And ultimately, neither should we put our trust in the saints, great or small. Like the apostles Peter and Paul, our trust is in the Lord, who lifts up the lowly, and makes them to live large.

✠