Last May saw the first fruits of a little-known but compellingly ambitious project of the Netherlands Bach Society. The project, called All of Bach, is exactly what it sounds like: they are performing and recording videos of every single piece Bach ever composed, from cantatas to sonatas to concertos to motets to organ and keyboard works of all kinds, and they are posting a new one online each week until they finish. To date, they’ve completed forty-six of Bach’s works, with 1,034 to go. (If you’re interested, the audio and video quality is superb and the performances even more superb: here are the Passacaglia in C minor [BWV 582] and the famous Cello suite no. 1 in G Major [BWV 1007], to pick just two.)

To my mind, Bach’s genius is unparalleled in the history of music, so I think this project is a fantastic treasure; even the mere idea of it is exciting. To perform and record all of Bach’s works is something similar to examining all of a master artist’s paintings or studying all of a prolific author’s books: the totality of these projects is what impresses, because in a way it connotes a sort of complete knowledge of the composer, painter, or author—or, at the very least, of his work. Could someone truly be called an expert on Flannery O’Connor without having become familiar with her complete works?

Still, even if such projects are completed, as the All of Bach project presumably will be in twenty years or so, truly comprehensive knowledge nonetheless remains out of reach. For one thing, not every piece Bach wrote saw the light of day—probably some were abandoned or simply lost to time. But there was more to Bach than his music anyway; even if one were to memorize every note of every piece he ever wrote and could give an astute explanation of why he composed how he did, there would be still more to know about him. And if we can’t hope to understand everything about even one man, how much less can we hope to exhaust the infinite intelligibility of God!

I’ve always loved the last verse of St. John’s Gospel: But there are also many other things which Jesus did; were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written (21:25). Even the deeds of the God-Man are only partially available to our intellects, at least here and now. We know many of the things that he said and did, because they are recorded in the Gospels, which are the “principal witness for the life and teaching of the incarnate Word, our savior” (Dei Verbum 18). All of Jesus’ words and actions are salvific, but there are some we don’t know about. Even if they were written down, St. John tells us, someone who spent his whole life learning about them wouldn’t finish! Far from inciting us to doubt and despair, this vast inexhaustibility not just of Jesus’ deeds on earth but even of God’s very essence instead inspires in us faith and hope—and love.

While it’s true that we can know something about Bach from his music and that we can know something about God from his effects, in both cases our knowledge remains imperfect and incomplete. We can never attain comprehensive knowledge of God; we can only plunge further and further into his infinite intelligibility, and as a result we come to love him more and more truly. But God’s knowledge of us is comprehensive; he does know every single thing there is to know about us. He is, as St. Augustine said, “more inward than the most inward place of my heart and loftier than the highest.” Just as no one could ever know more about Bach’s music than did the composer himself, so no one can know us more deeply than can the Creator himself. We’re not just knowers, we’re known knowers. We’re not mere musicologists, outside observers examining these things from afar—we’re the music! This consoling truth is voiced sublimely in Psalm 139, which begins:

O LORD, you search me and you know me.

You yourself know my resting and my rising,

you discern my thoughts from afar.

You mark when I walk or lie down;

you know all my ways through and through.

Before ever a word is on my tongue,

you know it, O LORD, through and through.

Behind and before, you besiege me,

your hand ever laid upon me.

Too wonderful for me, this knowledge;

too high, beyond my reach.

Our very knowledge of God’s exhaustive knowledge of us takes us beyond our reach—wonderfully so—and straight into the unfathomable mystery, in whom we hope to remain, knowing and being known by the Divine Composer for all eternity.

✠

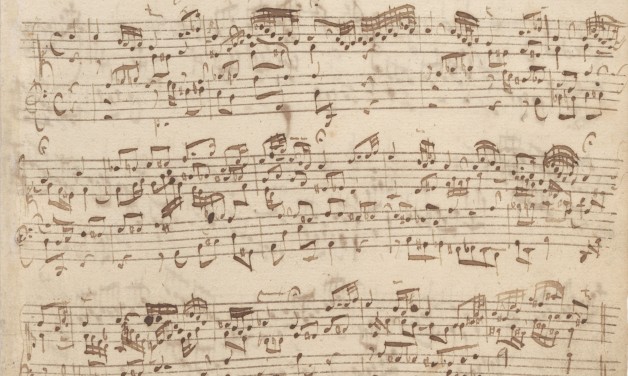

Image: J. S. Bach, Autograph Manuscript