Yesterday, the governor of Maryland signed a bill according homosexual unions the same legal status as marriage. Maryland, in now recognizing same-sex unions as marriages, has joined the ranks of seven states and the District of Columbia. The measure had previously been approved by the state Senate, but polls reveal the issue to be so contentious and the opinions of the citizens of the state to be so divided, it is likely the issue will remain unsettled until determined by a statewide referendum. How then have the debates surrounding the same-sex marriage issue become so divisive? Why does it seem that the defenders of Church teaching are simply talking past contemporary culture?

Throughout history, moral questions have typically been raised in the midst of some practical dilemma or dispute. A person’s beliefs, opinions, or inclinations are challenged in some way, and, as a result, he feels compelled to justify them. In today’s world, however, “justification” tends to take the form of unreflective “sound bites” or impassioned denunciation. Reasoned, critical investigation of moral principles is rare, and moral discourse tends to degenerate into the mere assertion of personal preference.

In such a climate, it is difficult to appeal to the Catholic natural law tradition or to the ordered nature of creation. Terms such as “teleology”—the study of the natural ends that are “built into” the natures of things—are distasteful or inaccessible to contemporary culture. For centuries, Christianity has taught that created things operate according to the limits of what they are. Oak trees, for instance, reproduce by dropping acorns, not puppies; and it’s the nature of an acorn to grow into an oak tree, not an aardvark.

Likewise, there are limits to the human condition; we can act productively or fruitfully in some ways and not in others simply because of the way in which we are. Because things have natures, they also act for an end. In fact, everything in the world, whether consciously or unconsciously, is striving towards the fulfillment of its nature. The end of the human person, as a rational animal, is happiness. And happiness is constituted, not by our preferences, but by what will make us flourish. Only certain things will make us flourish, and, therefore, only certain things will make us happy.

Twenty-first-century America, however, prefers to think that man can seek fulfillment by following his desires, his preferences. Accordingly, each person has a self-validating way of life; he is unable to make mistakes. A man can no more be wrong about what makes him “happy” than he can be wrong about any of his preferences. This is directly opposed not just to Christian moral thought, but also to the ancient philosophical tradition, coming especially through Plato and Aristotle and the schools they founded. It was clear to them that happiness is constituted by objective goods, about which it is quite possible to be mistaken—a supposition confirmed, we might add, by everyday experience.

Nowadays, it upsets people even to suggest that there might be such a thing as an objective moral order, but, in the dispute over same-sex marriage, we must cast off any fear of inquiry. Without careful reflection, people of faith will have little to contribute to the debate. In order to clearly articulate the beauty and fullness of Christian moral truth, Christians should be asking questions about “natures,” “essences,” and, in general, about what it means to act for an end or purpose. Such categories, whether proposed in precise philosophical terms or in more ordinary and familiar language, are essential to an adequate representation and defense of the Catholic teaching on same-sex marriage, among other things. Faith believes and reason affirms that human persons were made for a purpose—for something far greater, in fact, than our brief life on this earth. This is a truth that can be quite challenging to those who live only for the here and now.

✠

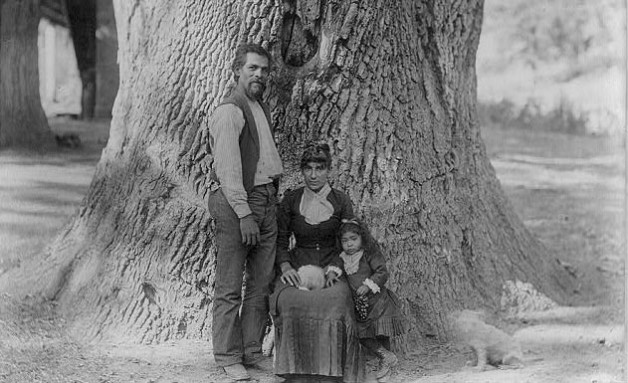

Image: C.E. Watkins, A Gigantic Oak Tree, an Indian Man, Woman, and Child, and a Dog, Kern County, California, 1888