Something about the news last week that physicists running the OPERA experiment at CERN in Switzerland had released observations suggesting that neutrinos travel faster than the speed of light left a bad taste in my mouth. It wasn’t anything about the experiment or the admirable way the scientists had grappled with the results for months before releasing the news. The nagging feeling was that I was playing the cop at a crime scene when my Dominican brothers would ask about it. “Nothing to see here, move along, check back in a few months, or years, when the data analysis has been quadruple-checked and corroborated by independent experimentation.”

Sure, it was the correct and responsible thing to do, and it’s exactly the way the experimentalists who released the findings behaved by asking the scientific community to scrutinize their results and see if something could have gone wrong. No amount of dazzling my brothers with stories of time slowing down, or beams traveling through the earth, or particles spontaneously changing from one form to another could assuage the feeling that I was being a bit of a wet blanket about the whole thing.

Some amount of weirdness comes into even the most mundane discussions of modern physics, but that doesn’t mean anything goes; physics is still bound by certain structures and principles, of which the inability to surpass the speed of light is one of the better established. So while destroying the hopes of my brothers for warp-speed travel and light sabers and photon torpedoes, trying to propose such oddities of physics as curved spacetime, ubiquitous invisible matter, or even the possibility of extra dimensions (mathematical, not parallel) seems like a poor exchange. As weird and wonderful as our world seen through the eyes of modern physics may be, it seems bound in a straitjacket compared to your favorite sci-fi or fantasy stories. The prospect of being a cosmic hall monitor telling the teacher on imaginations run wild was not what got me interested in physics so long ago, but the idea of a vibrant order and structure that mirrored some deeper truth behind it all.

As with so many of my best thoughts, G.K. Chesterton said this one better. In his “Ethics of Elfland” chapter from Orthodoxy, he says,

All the towering materialism which dominates the modern mind rests ultimately upon one assumption; a false assumption. It is supposed that if a thing goes on repeating itself it is probably dead; a piece of clockwork.

This contradicts our experience since “the variation in human affairs is generally brought into them, not by life, but by death; by the dying down or the breaking off of their strength or desire.” Our craving for excitement is a sign of boredom and dissatisfaction. If what we were doing now were truly animated and joy-filled we’d never get tired of it. In the same way, the orderly structure of the cosmos, where these conditions always lead to those results, is not a reflection of some cold, unthinking, inanimate realm. Rather it is a reflection of the living God, who out of all the unimaginable plethora of schemes for nature He could have chosen, and still could choose, gave us this one as an act of love.

The world He has loved into being is so beautiful and so irresistibly real that we can be lulled into the false sense that it could never have been any other way. Our fantasies and stories, as wonderful and entertaining and exciting as they may be, will never live up to the glorious universe we live in, and the scientist’s role is not to discourage and quash the creativity of man, but to extol and proclaim the divine creativity that has no equal.

While my answer to my brothers was right, that we should take a wait-and-see attitude on these new observations, perhaps my presentation is what needed correction. As far as we can surmise so far, the world is a more perfect place when Einstein’s theory of relativity and its universal speed limit holds. Our first assumption must be that there is some mistake in the data, but if evidence suggests that the result is true then we’ll need to consider what this might reveal about a greater order in the physical universe that we hadn’t had access to before. Either way, scientists will continue seeking to discover the rules to the most exciting game ever played, which God has never seen reason to be bored with.

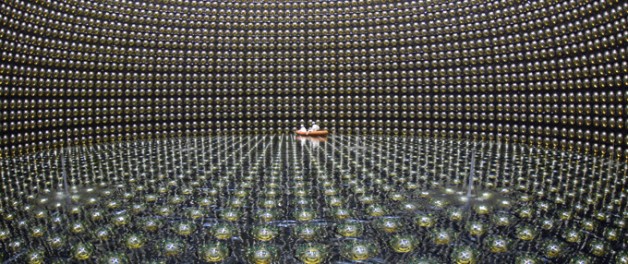

Image: University of Tokyo, Water-filling of Super Kamiokande Nucleon Decay Experiment, April 23, 2006