Anyone who has grown up with siblings likely knows the truth of the saying that those who are closest to us are oftentimes the ones who can hurt us the most. For some reason, people can be incredibly cruel in the way they treat those closest to them, and sometimes this is most clearly illustrated with young siblings. Children can get quite upset when their siblings or friends do something to hurt them, often rendered inconsolable. How many times have parents heard the phrase “I’m never going to speak to her again!” Often in the midst of these small (or sometimes considerable) crises, the call to love our neighbors becomes a point beyond consideration. Yet, it is precisely situations like these that can help us learn to love even those who commit unspeakable deeds of evil against us.

Why might siblings be the prime example for illustrating this perverse human tendency to injure those closest to us? Well, for one, siblings grow up with each other, spending the greater part of their days in each other’s company. Because they are in such close proximity, the one very easily gets to know what makes the other tick or, possibly, tip over the edge of sanity. I personally remember my parents often scolding my siblings and me for “pushing each other’s buttons.” I also have vivid memories of becoming incredibly perturbed when one of my brothers or sisters would proceed to do the exact thing that I had oh so kindly asked him not to do anymore. Of course, an even graver, more poignant example might be the case of betrayal. This is perhaps the ultimate way in which one sibling can use his knowledge to injure another. It is not exactly uncommon to hear of siblings who refuse to speak to each other for significant periods of time because of such traumatic experiences.

This more distressing aspect of our paradox touches on another reason why our siblings can often hurt us the most: we are brought up loving our siblings, and yet they can (and sometimes do) betray our love and trust by deliberately hurting us. Once that gift of love is rejected, we are easily led to believe that we carry little value in the eyes of one we love. As a result, such a sense of rejection can give rise to anger and resentment at the actions of our siblings, ultimately leading to hatred. What happens to the love then? If we cannot trust our siblings not to hurt us, how are we supposed to love them? Moreover, wouldn’t our love, in some way, condone the wrong they have done to us?

Of course it is counterproductive to withhold punishment from someone who needs to learn a lesson. In fact, sometimes love requires that we seek the correction of another’s faults, even to the point of extreme measures. Saint Augustine provides some useful insight in his rule for religious life. In the event that a brother discovers the grave misdeed of a confrere, Augustine urges the discovering brother to turn the other over for proper correction, or punishment, even if that means expulsion from the community. He observes that “even this [extreme measure] is not an act of cruelty but of mercy: to prevent the contagion of his life from infecting more people.” But even in such action, he advises “love for the person and hatred for the sin.” So, our concern in these matters is not just for the wellbeing of the community but also for the particular moral health and wellbeing of the offender. Thus, just and fitting punishment can be as much a work of love as it is a correction, and Augustine urges that love of the sinner and hatred for the crime should not part.

Of course, it remains quite a challenge to love our brothers and sisters whenever they harm us and as we cry out for vengeance, as did the blood of Abel against the crime of his brother. Love in such circumstances is not the easiest habit to acquire. Yet, Jesus Christ calls us to rise above doing what is easy and to pray for those who persecute us. Perhaps the best we can do is to pray, in the midst of this warfare, for those who harm us; pray that God, who heals us as he wounds (Job 5:17–18), may ultimately work out the salvation of even our most bitter rivals.

✠

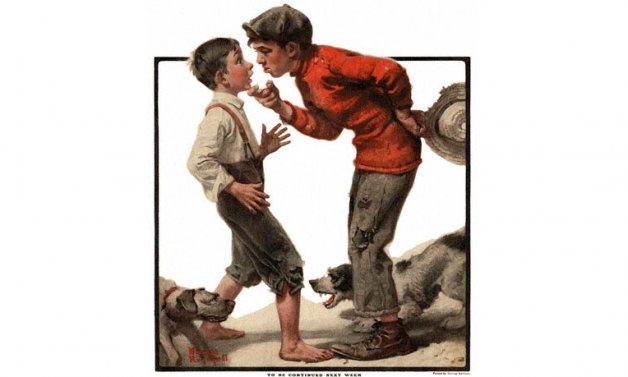

Image: Norman Rockwell, The Bully