¨Bob is Bob,” and “Dan is Dan;” these statements are tautologically true. Yet we also say that “Bob isn’t himself today,” and this manner of speaking gets at something profound. We can, somehow, be more or less “ourselves.” But what does that mean, exactly?

It doesn’t mean that personhood changes or disappears, or that someone becomes someone else. Rather, it is a statement about wholeness, completeness, and integrity of life; or the lack of integrity and that absence of a proper order in life—being scattered, fragmented. And there is, ultimately, only one thing that can destroy integrity: sin.

Sin wounds the nature of man and injures human solidarity. (Catechism of the Catholic Church 1849)

Sin is not an offense against an arbitrary standard concocted by a devious divinity. It’s an offense against reason and truth. As such, its effects are not only external, breaking the divine and eternal law, but also internal. It wounds human nature by destroying the proper ordering of life, by twisting nature to perverted counterfeits of the good it seeks. Sin makes us less ourselves.

All sin and vice lead us to lose ourselves, but some kinds more than others. This depends not only on the gravity of the offense, but also on the role that each virtue and vice plays in human life. One virtue is particularly important, and particularly neglected in our era: that of chastity. Chastity is especially important not because Christians are obsessed with controlling a particular, and personal, aspect of people’s lives, but because it reflects and informs integrity and self-possession throughout all facets of life.

The virtue of chastity therefore involves the integrity of the person and the integrality of the gift … Charity is the form of all the virtues. Under its influence, chastity appears as a school of the gift of the person. Self-mastery is ordered to the gift of self. (CCC 2337, 2346)

The proper ordering of life is, ultimately, one of self-mastery and self-gift, for “man cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself” (Gaudium et Spes, 24). Chastity is a virtue exemplifying both self-mastery and self-gift. Self-mastery, since “the alternative is clear: either man governs his passions and finds peace, or he lets himself be dominated by them and becomes unhappy” (CCC 2338). Self-gift, since “some profess virginity or consecrated celibacy which enables them to give themselves to God alone with an undivided heart in a remarkable manner,” and some profess vows “in the complete and lifelong mutual gift of a man and a woman” (CCC 2349, 2337). Chastity, thus, is worth our special concern.

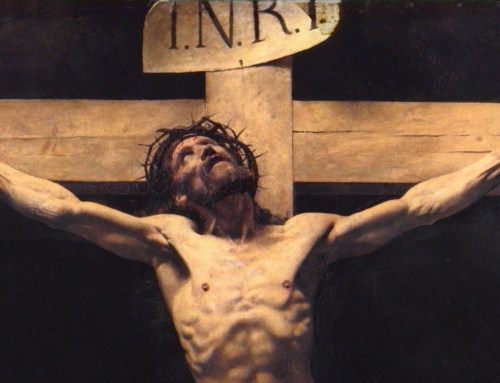

In today’s age, in a culture of explicit and unbridled and almost unavoidable unchastity, sin has harmed each of us, distorted your integrity and mine, in a drastic way. It is no surprise that so many people are “not themselves” and are unable to gather the scattered fragments of life. It may tempt us to despair, but we are comforted by our Savior and the confidence that “where sin abounded, grace did more abound” (Rom. 5:20). It is by grace, purchased at great price, that sin is expelled, virtue gained, and our selves made whole.

✠

Image: Konstantin Bogaevski, Desert. Tale. (detail)