The very first “Labor Day” was celebrated on September 5, 1882. While today the holiday is characterized by barbecues, the start of a new school year, and the end of the summer, it began as a fruit of the labor movement during the height of the Industrial Revolution. At that time, there was no “40-hour week,” but six, or even seven, twelve-hour days of work each week. In the 1880s this new holiday for workers was recognized by successive states’ legislation until it became a federal holiday in 1894. One hundred twenty-five years later, banks, non-essential government offices, schools, and many businesses still take Labor Day as a no-work day. While we enjoy our relaxation, though, do we still reflect on the purpose of such a day?

Ninety-nine years after that first Labor Day, John Paul II promulgated his encyclical on human work, called Laborem Exercens. While the pope comments on the changes in society and labor since the mid-19th century, he seeks to emphasize an enduring truth about man and his work. No matter the object of work, which varies drastically, the subject of work is always man (LE 5–6). We often and helpfully distinguish workers by their object: builders, doctors, teachers, technicians, soldiers, miners, scientists, etc. Each is defined by the kind of work they do. Even so, each builder, doctor, teacher, and so forth is a unique human being, the subject and agent of work. In our time, flooded with ideas of materialism, it is all too easy to evaluate work merely on the objective, productive side, and to forget the humanity of the agent who provides the work without which there would be no product. In this humanity, all of us are equal.

By no means does this equality demand that any work whatsoever be lauded as a masterpiece. Work retains its objective character. Whether the fruit of manual or intellectual labor, products vary in quality. Some buildings are more stable, more beautiful, or more useful than other ones. You or I may never produce art like Fra Angelico. Nonetheless, our human dignity remains intact, though unadorned with the praise owed to such an influential artist. On the other hand, the objective quality of products, because of their relation to their dignified subject—a human made in the image of God—can partake of man’s innate dignity. As John Paul II puts it, work can bear “the mark of a person operating within a community of persons” (LE, Prologue).

If, as John Paul II says, “the primary basis of the value of work is man himself,” then work is for the good of man and not the other way around (LE, 6). The pope argues that man is indeed destined for work but should not be enslaved by it. Labor conditions in the late 1800s were not conducive to upholding this arrangement. Frightfully low wages, unhealthy work environments, and often dehumanizing bosses upended the proper order of human relations to work. Man was made subordinate to that which should ennoble him.

Labor Day, therefore, seeks to provide a correction, not only by giving a day of physical rest, but by recalling for us that industriousness should promote the good of man, not swallow him up. Whether physical or intellectual, work will always involve toil and hardship. This hardship need not dehumanize man. On the contrary, by working through these toils “man not only transforms nature, adapting it to his own needs, but he also achieves fulfilment as a human being” (LE, 9). This fulfillment takes on a unique and encouraging form for Christians: “By enduring the toil of work in union with Christ crucified for us, man in a way collaborates with the Son of God for the redemption of humanity” (LE, 27).

✠

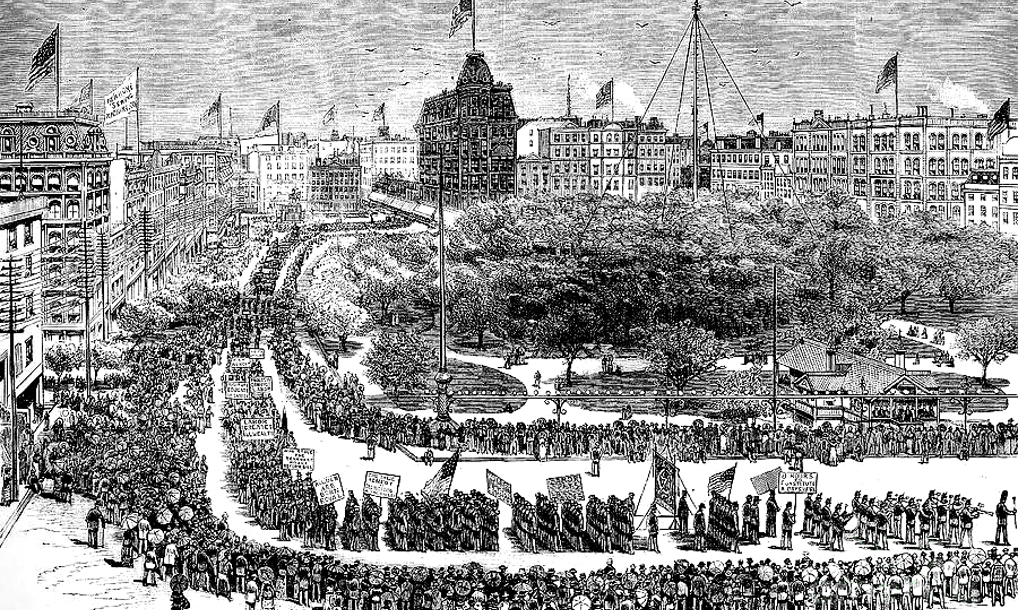

Image: Unknown Author, Labor Day Parade, Union Square, New York, 1882